Babymaxxing

+1 Son

And so the day came, August 12, our first child joined the world:

Given how great early life interventions work, I started immediately with important topics like British history:

Kidding aside, I've been doing some reading of the pro-fertility blogs, in line with my recent writings and research on the topic (see here and here and here and here and here). I meant to read Bryan Caplan's book (Selfish Reasons to Have More Kids, 2021), but instead got started on a different book (Family Unfriendly: A Critical Examination of Overparenting and Its Consequences, 2024, Timothy P. Carney). I am familiar with most of Caplan's writings already, so that perhaps factored into why I read this one first. The Carney book is written from a religious Christian perspective (Caplan is an atheist I assume as are we), but I suspect it covers many of the same topics. The TL;DR is you don't have to be so afraid of parenting because it is easier than you think once you give up on helicopter parenting, and just accept however the children turn out, at least, broadly speaking. So just concentrate on making your own life easier, have more children, and don't worry about 10 different after-school activities, private tutors, selective pre-school, and so on.

But also, of course, I couldn't help myself, so when I got the measures from his birth, I looked them up in growth charts asked AI to convert them to centiles. This is what Grok told me:

Weight (3750 g or 3.75 kg):

Average birth weight for male North European newborns is approximately 3.5–3.6 kg, with a standard deviation of about 0.5 kg.

3.75 kg is slightly above the mean, likely placing it around the 60th–70th percentile. This is an estimate, as exact percentiles depend on the latest 2025 data.

Length (52 cm):

Average birth length for male newborns is about 49–50 cm, with a standard deviation of around 2–3 cm.

52 cm is above average, suggesting a percentile of approximately 75th–85th percentile.

Head Circumference (36 cm):

Average head circumference at birth for males is about 34–35 cm, with a standard deviation of about 1.5 cm.

36 cm is slightly above average, likely falling in the 60th–70th percentile.

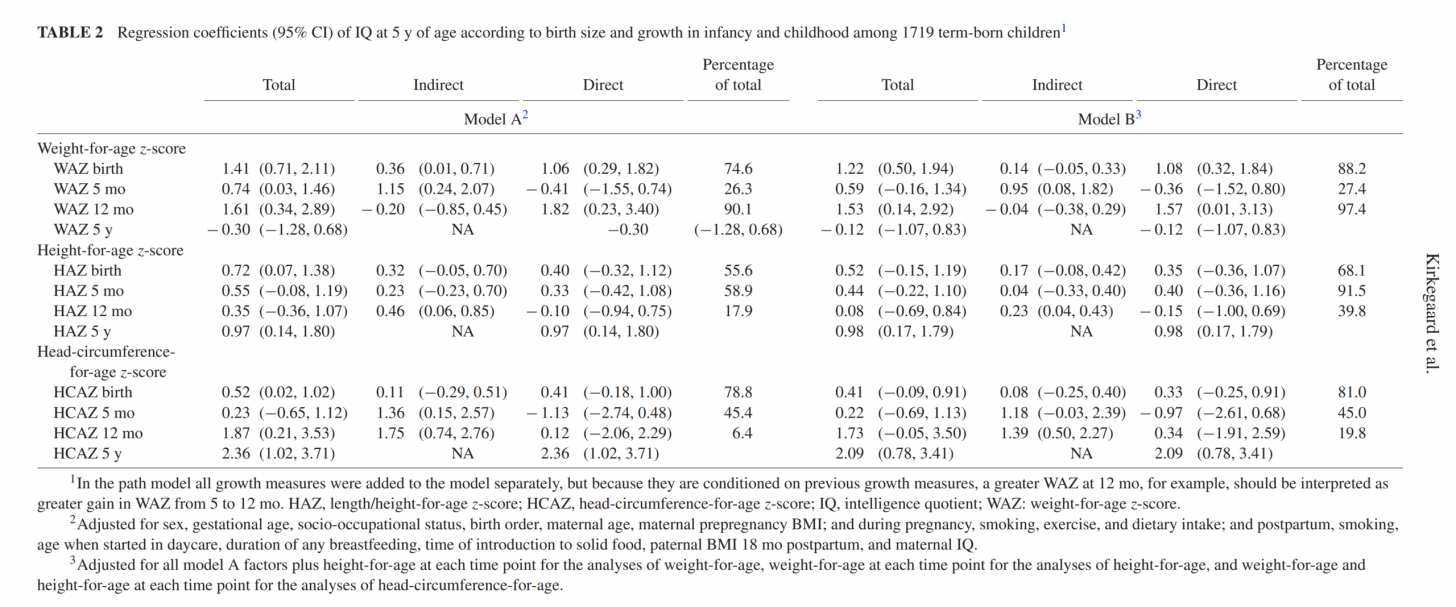

While any parent would probably feel good about their newborn having above average values, these metrics aren't that important. The most obvious one, head circumference, presumably relates to brain size later in life, which relates to intelligence. But children grow at different speeds, so how much does it really predict? I found a study, fittingly from Denmark and improbably even authored by a not-Emil Kirkegaard (2947 people in Denmark have this last name, thus 0.05% or 1 in ~2000 people):

They measured weight, height, and head circumference at 4 ages, and related this to IQ measured at age 5 using a Wechsler battery. Unfortunately, they controlled for a bunch of stuff in the usual kitchen sink/Everest approach (see footnote 2), so these aren't exactly the numbers we want. Anyway, what we can learn from these is that the associations are quite weak even unadjusted. Head circumference at birth (HCAZ birth) predicts 0.52 IQ higher at age 5 per standard deviation. That is to say, the correlation-equivalent (std. beta) is about r = 0.035. This was only barely p<5% with their sample size of 1800 children. The other betas weren't much better: weight 1.41 IQ (beta = 0.076) and height 0.72 IQ (beta = 0.048). As such, sure, these metrics have some positive validity, but it is too small to care about unless you are a researcher. Parents can stop worrying about these unless their child is very small, in which case, the problem is probably not the size metrics in themselves, but pre-term birth that is to blame. A 2011 meta-analysis of pre-term birth and IQ found a whopping -12 IQ association between families. Again, don't worry too much about this giant effect because it mostly reflects differences in life history speed between families. If we instead compare only full-siblings, the association is much weaker, as shown by another Danish register study:

Results Among 792 724 full siblings in the cohort, 44 322 (5.6%) were born before 37+0 weeks of gestation. After adjusting for multiple confounders (sex, birth weight, malformations, parental age at birth, parental educational level, and number of older siblings) and shared family factors between siblings, only children born at <34 gestational weeks showed reduced mean grades in written language (z score difference −0.10 (95% confidence interval −0.20 to −0.01) for ≤27 gestational weeks) and mathematics (−0.05 (−0.08 to −0.01) for 32-33 gestational weeks, −0.13 (−0.17 to −0.09) for 28-31 gestational weeks, and −0.23 (−0.32 to −0.15) for ≤27 gestational weeks), compared with children born at 40 gestational weeks. In a nested sub-cohort of full brothers with intelligence test scores, those born at 32-33, 28-31, and ≤27 gestational weeks showed a reduction in IQ points of 2.4 (95% confidence interval 1.1 to 3.6), 3.8 (2.3 to 5.3), and 4.2 (0.8 to 7.5), respectively, whereas children born at 34-39 gestational weeks showed a reduction in intelligence of <1 IQ point, compared with children born at 40 gestational weeks.

It should be pointed out that the causality is tricky. Even these sibling results don't prove that pre-term birth in itself is causal because it can be that life history speed, including natural gestation length, is partly controlled by (some of the) same genes as intelligence is. These values thus do not necessarily reflect causality from the earlier birth.

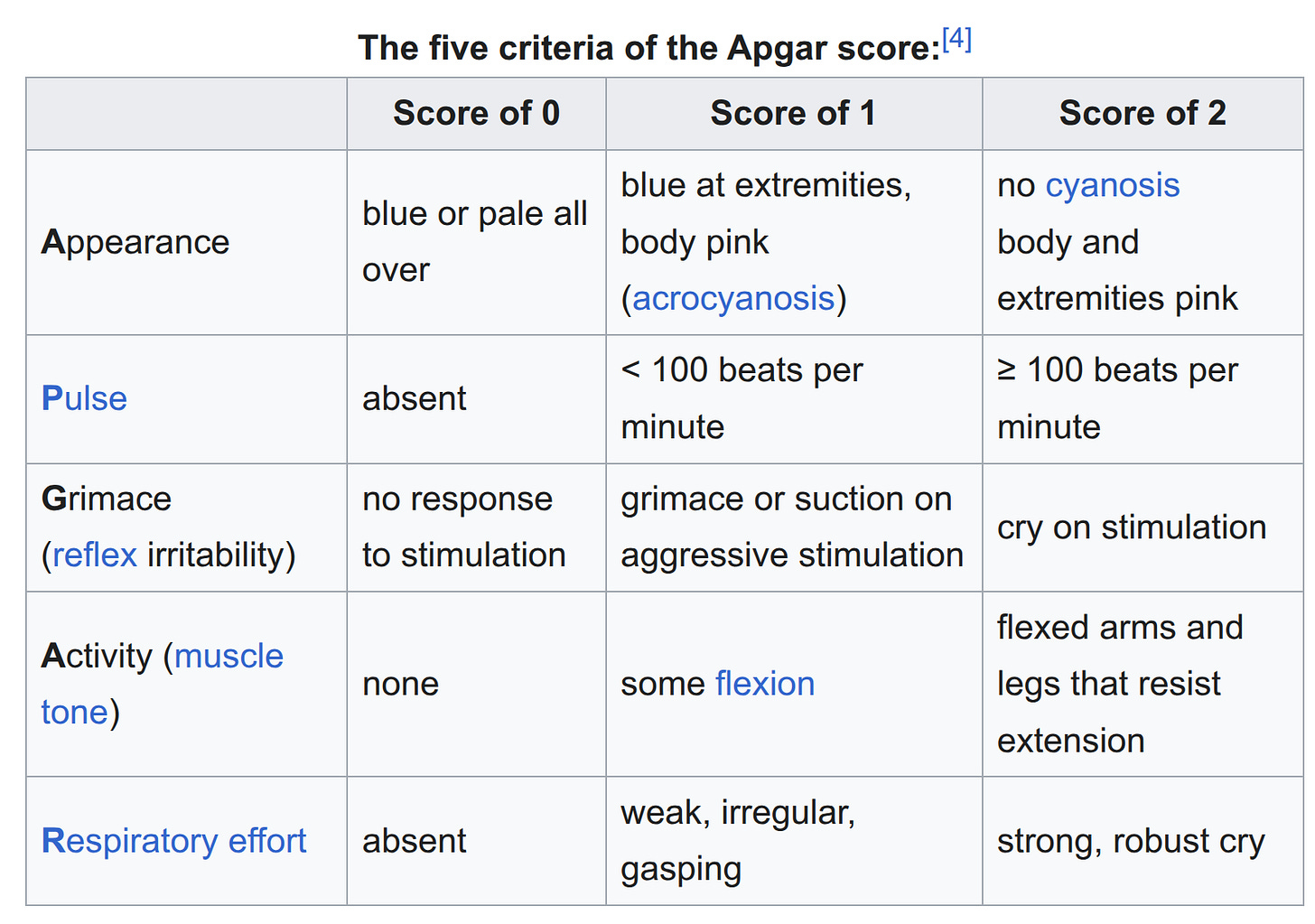

Also related to birth is the Apgar score, which is a simple composite of good neonatal functioning. We weren't provided with this score, but:

I guess ours was 10/10. I was present at the birth and cut the umbilical cord. The birth itself was fairly quick (9.5 hours from onset of contractions to birth) and relatively uneventful.

After these birth metrics come the developmental metrics, of which I think the most commonly used is the Bayley Scales of Infant Development, used to "assess the development of infants and toddlers, ages 1–42 months". Again, these aren't too much to worry about either because they aren't very reliably measured and don't predict adult outcomes well either. Sadly, I didn't find a Danish study about this as well, but I found a Swedish one, which found:

The study aim was to explore the relationship between a developmental assessment at preschool age and an intelligence quotient (IQ) assessment at school age. One hundred sixty-two children were assessed at 2.5 years with the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development—Third Edition (Bayley-III) and then at 6.5 years with the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children—Fourth Edition (WISC-IV). The Bayley-III Cognitive Index score was the Bayley entity that showed the highest correlation with WISC-IV Full-Scale IQ (FSIQ; r = .41). There was a significant difference between the individual WISC-IV FSIQ and the Bayley-III Cognitive Index scores. Analyses showed an average difference of −4 units and 95% limits of agreement of −18.5 to 26.4 units. A multivariate model identified the Bayley-III Cognitive Index score as the most important predictor for FSIQ and General Ability Index (GAI), respectively, in comparison with demographic factors. The model explained 24% of the total FSIQ variation and 26% of the GAI variation. It was concluded that the Bayley-III measurement was an insufficient predictor of later IQ.

So even when this behavioral index was measured at age 2.5 and correlated with regular IQ tests from age 6.5 (4 years later), the correlation was only 0.41. I mean, it is certainly better than the 0.035 from head circumference at birth, but it ain't great either. One could make better predictions of how children turn out intelligence-wise by just averaging their parents' IQs instead, and even better, adding a polygenic score on top. And speaking of those, since many people were asking, no, we didn't use embryo selection. We rolled the genetic dice the old fashioned way. Amusingly, this might enable us to do a Gattaca 'replication' study, since the first born can be compared with later-borns that were conceived using such technology. We do intend to use embryo selection in the future, though it requires jumping around legal hoops as it is legally questionable or straight up illegal in most Western countries.

And no, I don't have any moral qualms about doing such an informal experiment either. I think parents, ourselves included, are perfectly capable of living their children, even if they aren't equal. We are certainly having a lot of fun with our baby so far.

Share your own baby stories in the comments!

Talk talk talk to your baby. Talk in the home, in the car and in the apark and in the store. Most people are dead silent around their babies and toddles, or on the phone. I talk to every baby I see and they all react positively -- their parents are often surprised. It has been a while since my kids were babies but there is somethig like a 10 to 1 difference between Middle class and welfare class parents in terms of talking. Then.... read read read. No TV in the house. Books books books..... (BTW, Babies are the best)

Congratulations!