Bedsharing/cosleeping and SIDS

Looking into the evidence for health advice

There is probably going to be a lot of baby-related science posting. You will have to forgive me. On the other hand, my own reader survey shows that the fertility rate of the blog readers (those who fill out the surveys anyway) are quite fertile (1.58) compared to the usual intellectual norms, and 4 of my friends have recently had children, so perhaps you will find this relevant.

At the hospital after birth, it seems most medical staff are instructed to tell you about how to sleep with the baby, or rather, make the baby sleep. Their advice is always the same from what I hear: don't sleep with the baby in the same bed. If you google this, you will find hundreds of pages about the dangers of bedsharing because of SIDS. The first thing on Google for me is the Lullaby Trust (co.uk), which provides this appropriately woke video:

At the 1:00 mark, their guidance is explicitly made with the goal of reducing the risk of SIDS. So what is SIDS exactly? Well, it means Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. It's not a real syndrome (a cluster of related symptoms), but actually a leftover diagnosis category that just means the cause of death is unknown. Wikipedia:

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), sometimes known as cot death or crib death, is the sudden unexplained death of a child of less than one year of age. Diagnosis requires that the death remain unexplained even after a thorough autopsy and detailed death scene investigation.[2] SIDS usually occurs between the hours of midnight and 9:00 a.m.,[3] or when the baby is sleeping.[4] There is usually no noise or evidence of struggle.[5] SIDS remains one of the leading causes of infant mortality in Western countries, constituting almost 1/3 of all post-neonatal deaths.[6]

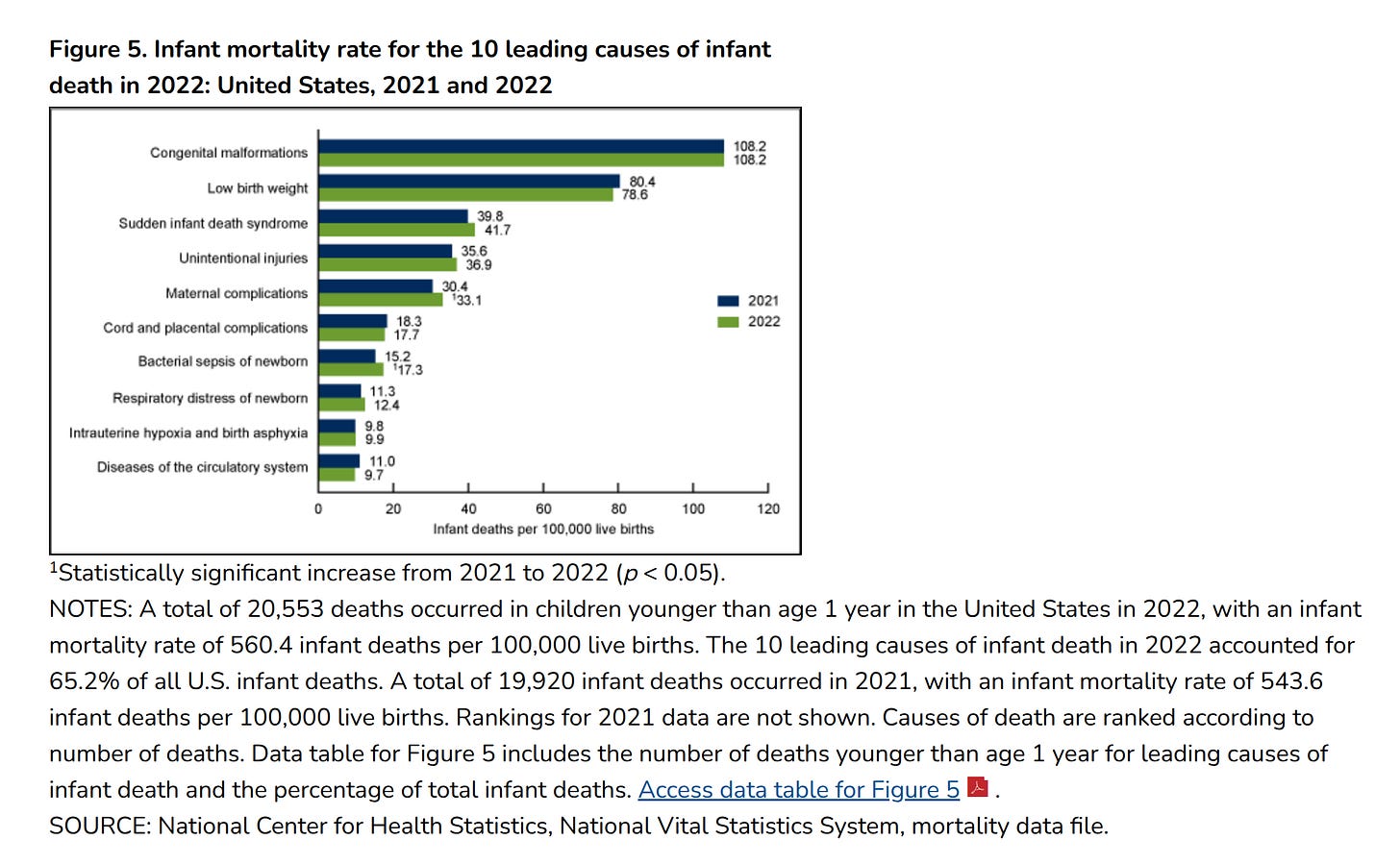

Supposedly, SIDS is related to bedsharing, which is why the advice is given. So of course I decided to check up on whether this evidence is plausible or not. First off, it is important to get the numbers into perspective. So let's look up like some rates, in this case, for the USA via CDC:

Note the denominator is 100,000. As such, the total mortality chance before 1 years of age is 560/100k, or 0.56%, or about 1 in 200. This is already very low. Of these, SIDS accounts for 42 deaths, thus 0,042% or about 1 in 2500 infants. This is a very low mortality rate from this cause.

Now, I don't know about your babies, but our boy loves to sleep with mom, and mom loves it too. It comes naturally, whereas forcing sleeping separately seems unnatural. I've checked the anthropological literature, and they confirm that co-sleeping in close proximity is the human norm until Westerners recently decided against it. It would appear sensible to posit that this is the evolutionary preferred sleeping pattern. The benefits are rather obvious: 1) baby doesn't freeze, 2) baby is close to the breast for feeding, 3) baby doesn't feel anxious due to separation, and 4) mother can easily check up on the baby and easily hear it. Western medicine has decided to intervene against this because we think we know better. It is not impossible we do so, but let's look at the evidence.

McGarvey et al 2005, Irish data:

Background: It is unclear if it is safe for babies to bed share with adults. In Ireland 49% of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) cases occur when the infant is bed-sharing with an adult.

Objective: To evaluate the effect of bed-sharing during the last sleep period on risk factors for SIDS in Irish infants.

Design: An 8 year (1994–2001) population based case control study of 287 SIDS cases and 831 controls matched for date, place of birth, and sleep period. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated by conditional logistic regression.

Results: The risk associated with bed-sharing was three times greater for infants with low birth weight for gestation (UOR 16.28 v 4.90) and increased fourfold if the combined tog value of clothing and bedding was ⩾10 (UOR 9.68 v 2.34). The unadjusted odds ratio for bed-sharing was 13.87 (95% CI 9.58 to 20.09) for infants whose mothers smoked and 2.09 (95% CI 0.98 to 4.39) for non-smokers. Age of death for bed-sharing and sofa-sharing infants (12.8 and 8.3 weeks, respectively) was less than for infants not sharing a sleep surface (21.0 weeks, p<0.001) and fewer bed-sharing cases were found prone (5% v 32%; p = 0.001).

Conclusion: Risk factors for SIDS vary according to the infant’s sleeping environment. The increased risk associated with maternal smoking, high tog value of clothing and bedding, and low z scores of weight for gestation at birth is augmented further by bed-sharing. These factors should be taken into account when considering sleeping arrangements for young infants.

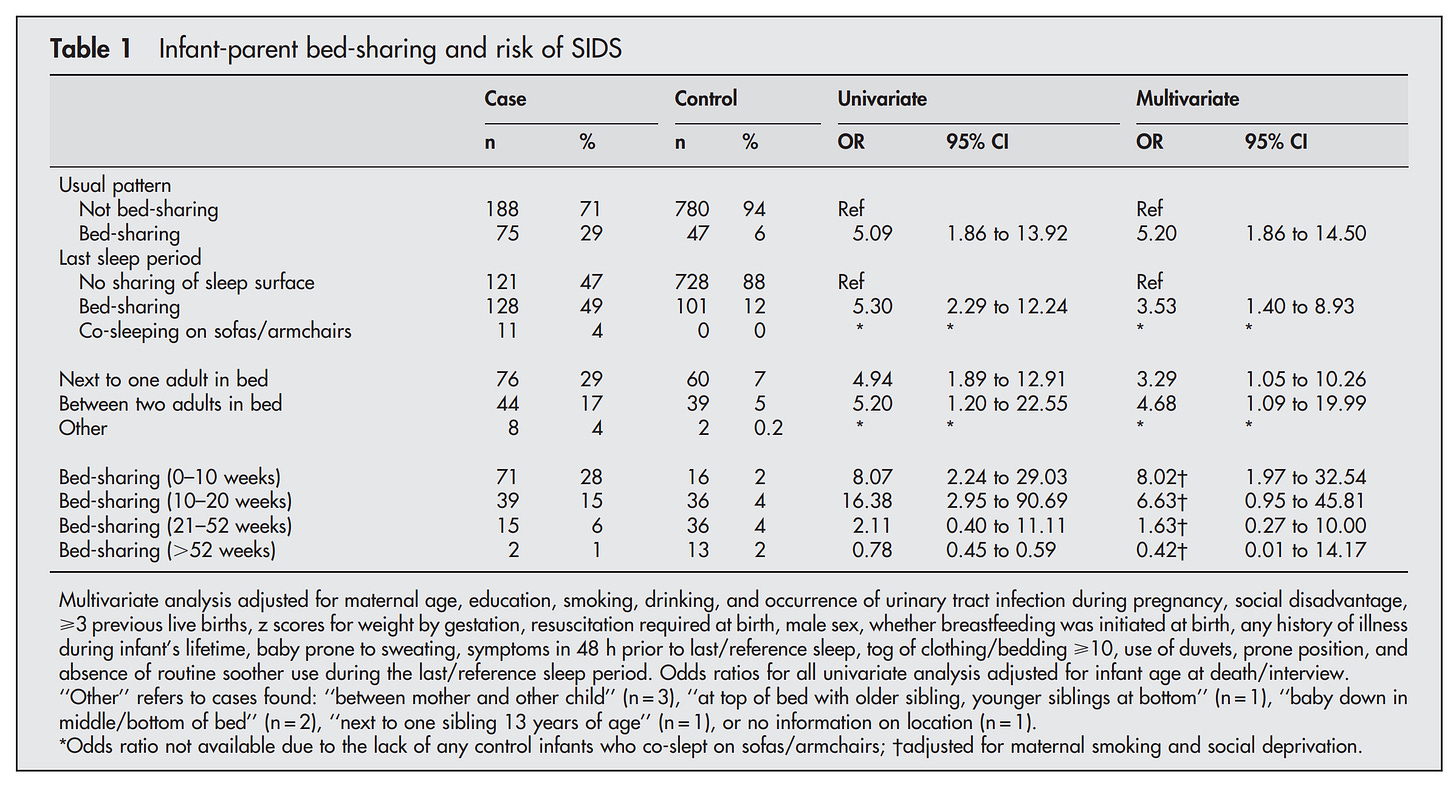

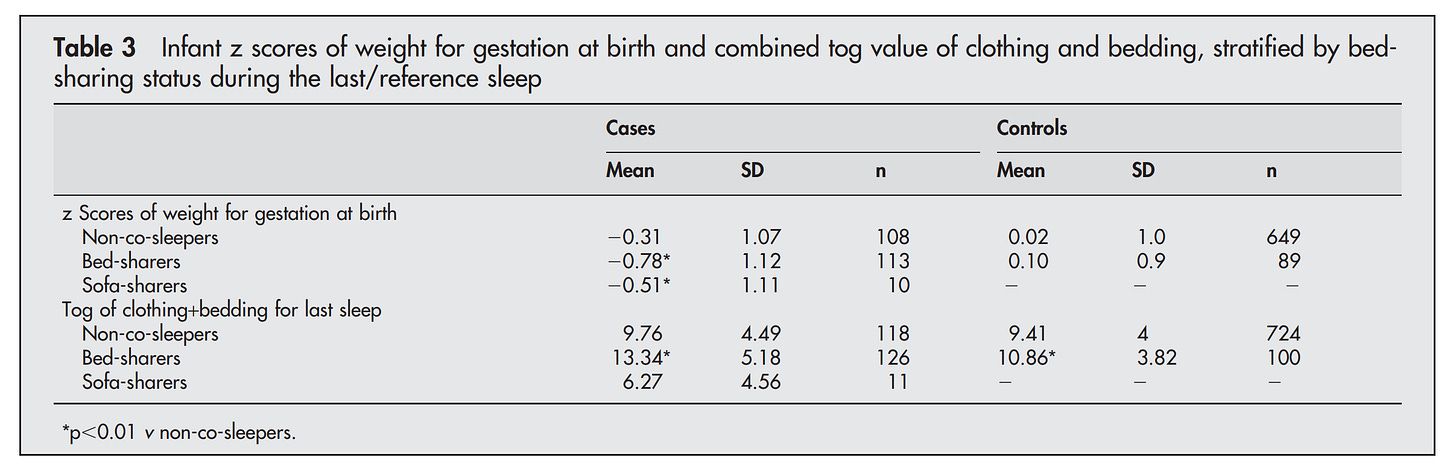

Due to the rarity of the deaths, usually studies must compile national data from multiple years to get sufficient data for analysis. Here's their main table:

Their multivariate analysis basically throws everything into the model that could plausibly be taken as a confounder (a cause of SIDS that correlates with bedsharing) and yet the signal remains (OR before 5.30 and after 3.53 controls). The problem is that bedsharing has all sorts of negative associations with parents and their behaviors. For instance, in this study from US Oregon by Lahr et al 2007:

Results: 1867 women completed the survey in 1998–99 (73.5% weighted response rate). Of the respondents, 20.5% reported bedsharing always, 14.7% almost always, 41.4% sometimes, and 23.4% never. In multivariable logistic regression, Hispanics (adjusted odds ratio [ORa] 1.69, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 1.17–2.43), blacks (ORa 3.11, 95% CI 2.03–4.76) and Asians/Pacific Islanders (ORa 2.14, 95% CI 1.51–3.03), women who breastfed more than 4 weeks (ORa 2.65, 95% CI 1.72–4.08), had annual family incomes less than $30,000 (ORa 2.44, 95% CI 1.44–4.15), or were single (ORa 1.55, 95% CI 1.03–2.35) were more likely to bedshare frequently (always or almost always). Among Hispanic and black women, bedsharing did not vary significantly by income level. Bedsharing black, American Indian/Alaska Native and white infants were much more likely to be exposed to smoking mothers than Hispanic or Asian/Pacific Islander infants (p < .0001).

Similarly, we know that SIDS cases are generally worse off even before death:

Possibly the best study on SIDS is that by Carpenter et al 2013, which pooled data from 5 studies from Western countries (including the one above):

Objective To resolve uncertainty as to the risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) associated with sleeping in bed with your baby if neither parent smokes and the baby is breastfed.

Design Bed sharing was defined as sleeping with a baby in the parents’ bed; room sharing as baby sleeping in the parents’ room. Frequency of bed sharing during last sleep was compared between babies who died of SIDS and living control infants. Five large SIDS case–control datasets were combined. Missing data were imputed. Random effects logistic regression controlled for confounding factors.

Setting Home sleeping arrangements of infants in 19 studies across the UK, Europe and Australasia.

Participants 1472 SIDS cases, and 4679 controls. Each study effectively included all cases, by standard criteria. Controls were randomly selected normal infants of similar age, time and place.

Results In the combined dataset, 22.2% of cases and 9.6% of controls were bed sharing, adjusted OR (AOR) for all ages 2.7; 95% CI (1.4 to 5.3). Bed sharing risk decreased with increasing infant age. When neither parent smoked, and the baby was less than 3 months, breastfed and had no other risk factors, the AOR for bed sharing versus room sharing was 5.1 (2.3 to 11.4) and estimated absolute risk for these room sharing infants was very low (0.08 (0.05 to 0.14)/1000 live-births). This increased to 0.23 (0.11 to 0.43)/1000 when bed sharing. Smoking and alcohol use greatly increased bed sharing risk.

Conclusions Bed sharing for sleep when the parents do not smoke or take alcohol or drugs increases the risk of SIDS. Risks associated with bed sharing are greatly increased when combined with parental smoking, maternal alcohol consumption and/or drug use. A substantial reduction of SIDS rates could be achieved if parents avoided bed sharing.

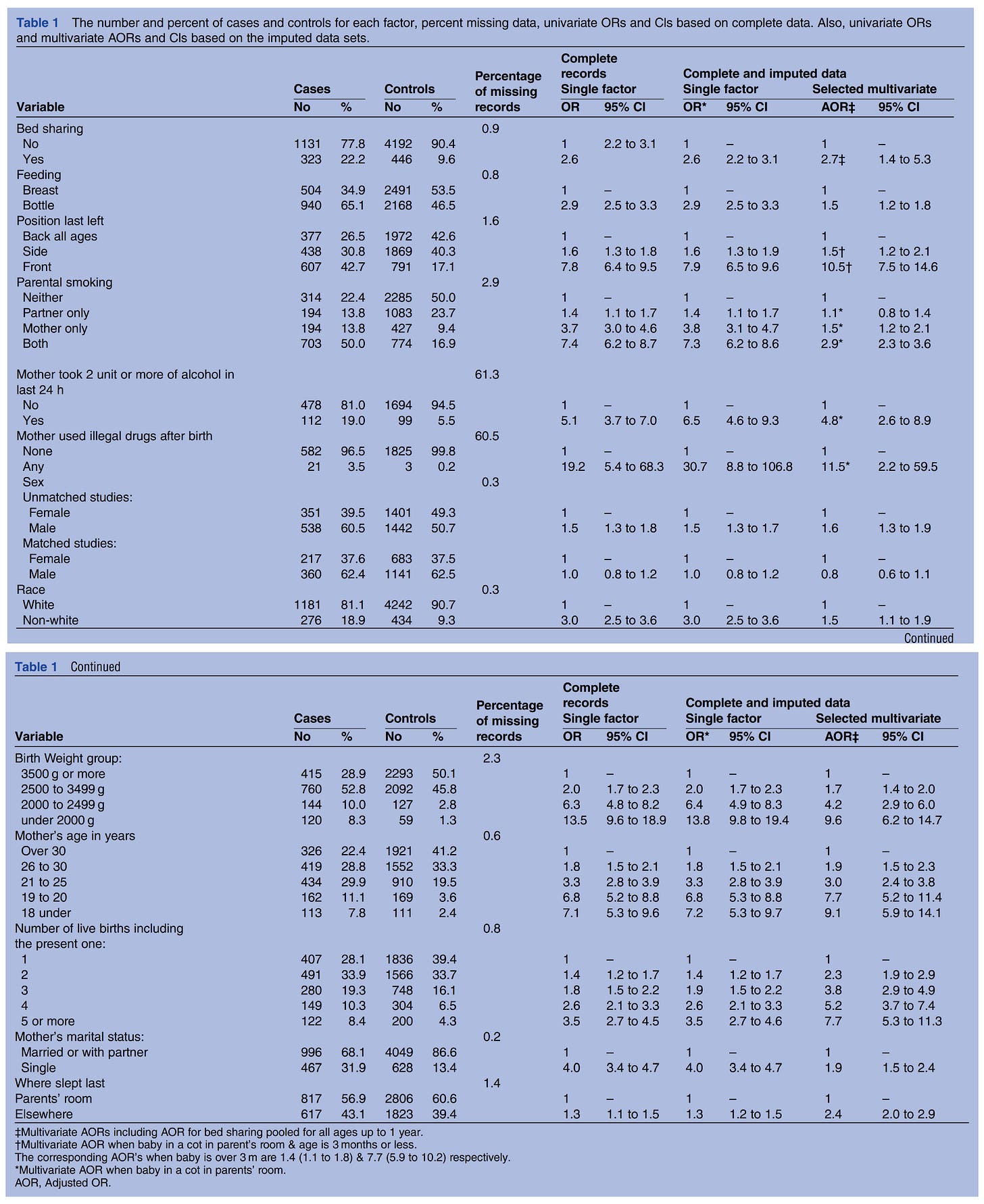

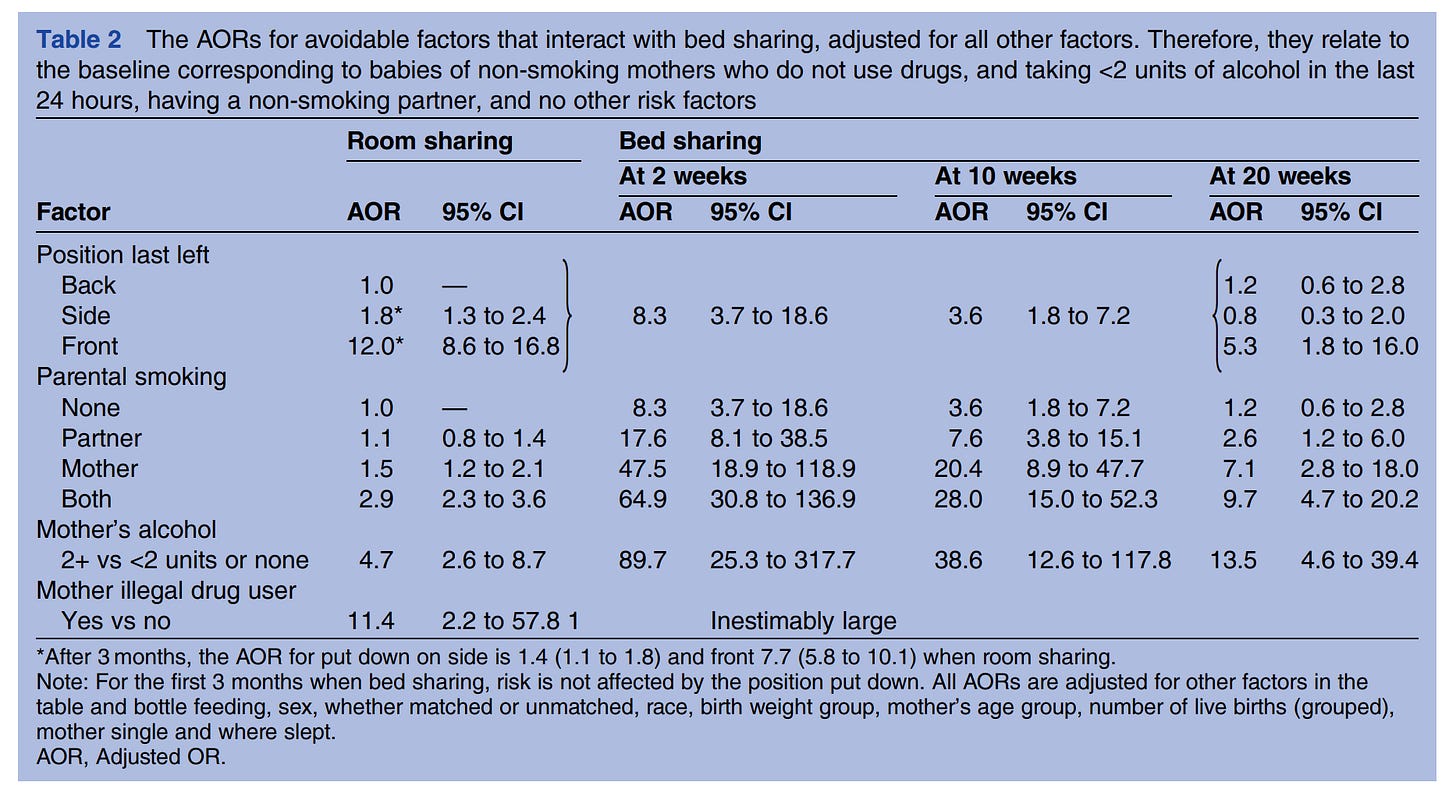

Using the large aggregated dataset they had relatively high power to investigate various claims about interactions (such as that between smoking and bedsharing) and subgroup analysis (poor man's equivalent to interactions). The large regression table gives the results:

The table shows the main effects only, and from both single-predictor models and the full model. Thus, we can learn that the combined dataset shows that bedsharing is 2.6 times the odds ratio of SIDS compared to sleeping not-together without any adjustments, and 2.7 when adjusted. Thus, strangely, adjusting for confounders made the risk become greater for bedsharing. This was possibly just due to sampling error as the confidence intervals are still quite wide (2.2-3.1 without adjustments, 1.4-5.3 with adjustments). Nevertheless, this is a concern because adjusting for numerous confounders should in general decrease the association, unless it is 100% causal in nature to begin with. This is unlikely given the associations reported between bedsharing and other variables in the Oregon study, e.g. non-European race, which was also confirmed in this study as being an independent risk factor (2.5 unadjusted, 1.5 adjusted).

What about interactions? Maybe bedsharing is only bad because smoking mothers do it and smoking in combination with bedsharing is the problem, perhaps because of cigarette smoke. Not so say the authors, who looked into these interactions:

The adjusted ORs are in comparison with 1 for the reference class (non-smoking, non-drinking, non-drug mothers). The authors don't actually report the p values of the interactions as far as I can tell, and interactions in logistic models can be hard to differentiate from combined effects due to the log-odds scaling. In any case, we see that age of the baby has a large effect (not reported in table 1 for some reason), bedsharing appears to be especially dangerous in the first few weeks, which is problematic because this where it is the most common and the baby demands it the most. It's especially bad if the mother was drinking (90x OR of SIDS), and "inestimably large" if the mother is also an illegal drug user.

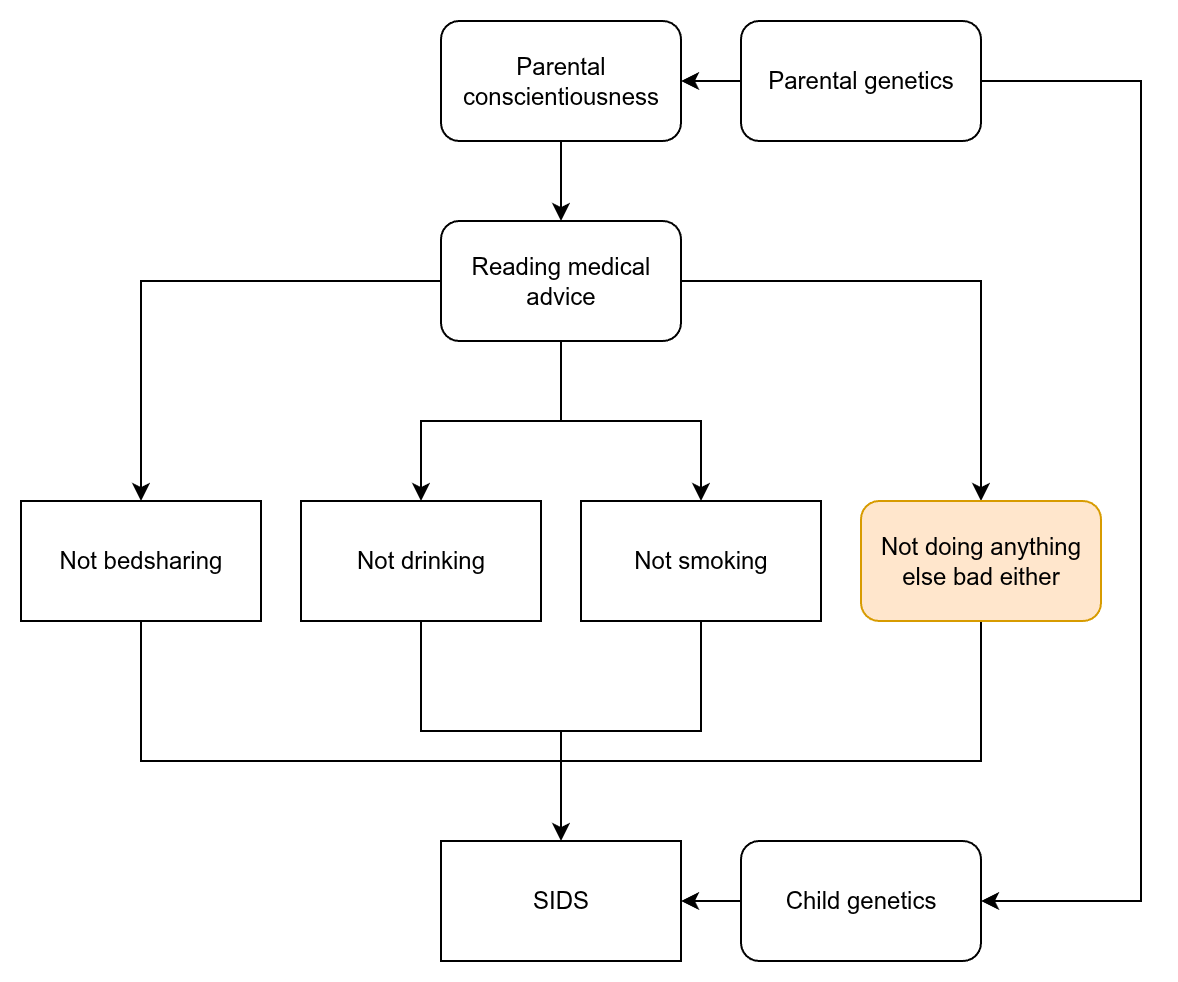

More or less, the authors controlled for every proposed confounder in the medical literature and found that bedsharing is still associated with non-trivial risk increases of SIDS. Nevertheless, causality is unclear. My worry is this:

There is a host of other associated but unmeasured behaviors, any of which could be important. Since the authors controlled for a large number of plausible candidates, this is a worry, but not a big worry. A bigger worry is that the measures are presumably based on self-report, and if your child died, maybe due to your own negligence or slightly on purpose behavior in drunken stupidity, perhaps you aren't so likely to fill out the questionnaire honestly (tantamount to admitting to manslaughter or murder).

Furthermore, genetics confounds everything, and is related to parental personality, which I've here labelled conscientiousness. We can see that this is likely in effect because looking back the table 1, we can see the typical SES-related predictors of SIDS:

Mother's age: younger is worse which is biologically implausible but makes sense as a confound of social class.

Number of children: more is worse, which again makes sense from a social class and careful mothering perspective, but not from a biological. If anything experienced mothers should do better.

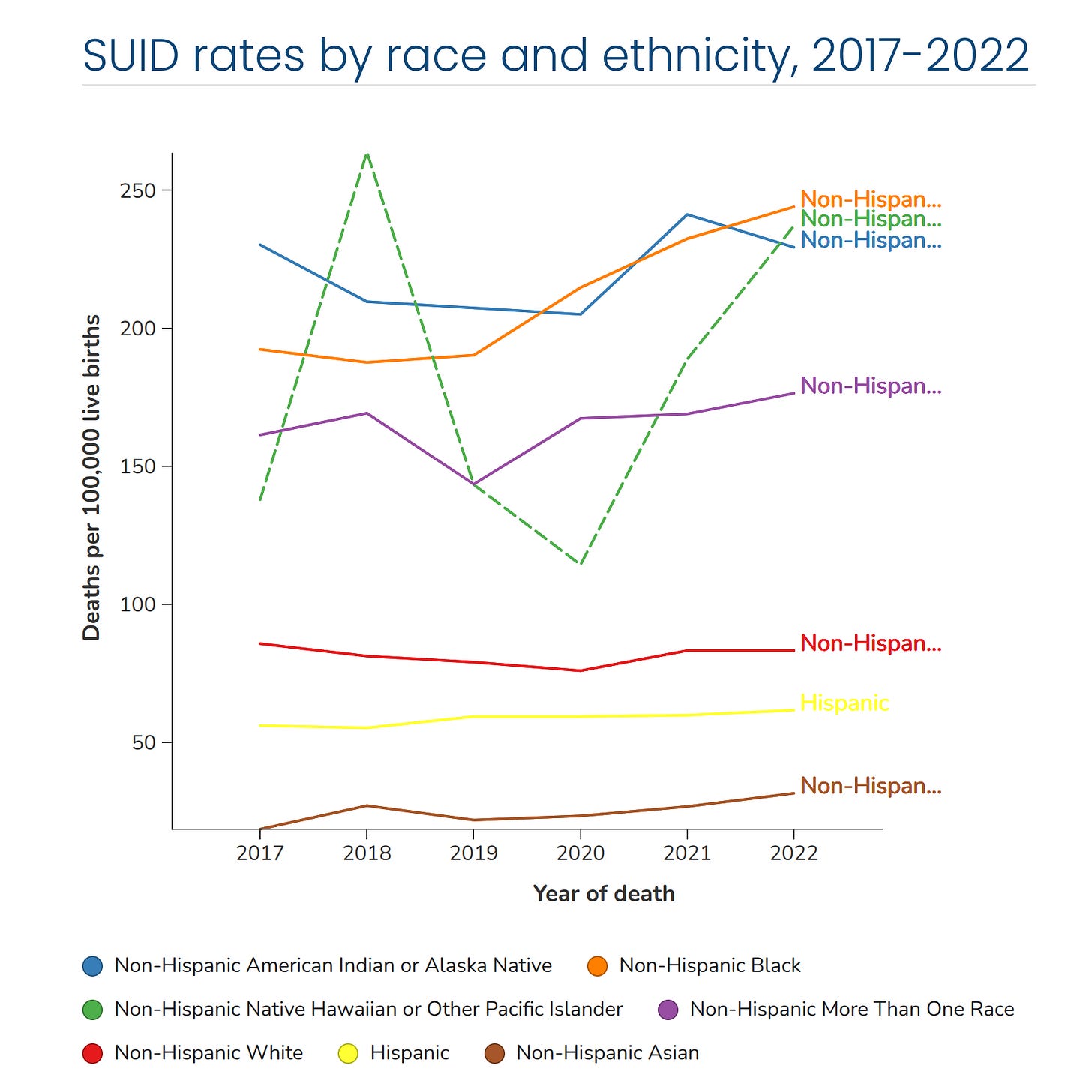

Given this SES gradient, there is another macabre angle. Given how rare SIDS is, it is not impossible that some large fraction of these cases are due to infanticide. Infanticide rates show the same SES and race relationships as SIDS do. Again, CDC data by race:

A 2021 study of US rates of infanticide by Salihu et al found that Blacks had 1.23 rate of Whites and Hispanics 1.10 of Whites, while "Others" had a rate of 0.92 of Whites. Given the other violent crime rates, these numbers would appear to be too small (Black-White homicide ratio is usually around 8x, but a large number of unsolved cases means this relative rate is probably higher). This could mean that some cases of infanticide are misclassified as SIDS for these groups.

Speaking of genetics, yes, Danish researchers Glinge et al 2023 have checked whether SIDS runs in families and found that it does:

Results In a population of 2 666 834 consecutive births (1 395 199 [52%] male), 1540 infants died of SIDS (median [IQR] age at SIDS, 3 [2-4] months) during a 39-year study period. A total of 2384 younger siblings (cases) to index cases (first sibling with SIDS) were identified. A higher rate of SIDS was observed among siblings compared with the general population, with SIRs of 4.27 (95% CI, 2.13-8.53) after adjustment for sex, age, and calendar year and of 3.50 (95% CI, 1.75-7.01) after further adjustment for mother’s age (<29 years vs ≥29 years) and education (high school vs after high school).

Conclusions and Relevance In this nationwide study, having a sibling who died of SIDS was associated with a 4-fold higher risk of SIDS compared with the general population. Shared genetic and/or environmental factors may contribute to the observed clustering of SIDS. The family history of SIDS should be considered when assessing SIDS risk in clinical settings. A multidisciplinary genetic evaluation of families with SIDS could provide additional evidence.

Familial similarity unfortunately does not tell us why it runs in families. It can be because some families have rare genetic disorders which may cause multiple children to due unexplainably (e.g. of heart failure), or it may be due to heritable or environmentally transmitted parental behaviors (drinking, poor sleep management, or violent tendencies). Researchers from Utah have also confirmed these results using multi-generational records from their registers Christensen et al 2016 (amusingly, also of Danish origin, God bless the Mormons).

In theory, it is possible to do a sibling control study for this scenario. However, given how rare the outcome is, it is probably not going to happen. So to get certain information about causality, we would probably have to turn to randomized trials (many would consider this unethical) or better, natural experiments using dates of parental advice change. This latter method has been used to show that the incidence of SIDS declined following the introduction of sleep-on-the-back advice (see the same Utah study above). But note also that SIDS rates can fall for other reasons because as a leftover category, better diagnostics or changes in diagnostic practices also lead to changes in SIDS rates. These data are inherently difficult to interpret.

I honestly don't know if bedsharing causes SIDS or not, and neither does anyone else. However, even if it does cause some increased risk, it may be worth it if this causes people to have more children. After all, trying to prevent a fraction of a 0,042% (~1 in 2500 infants) chance of infant death at the cost of having even 0.1 fewer children on average is a VERY net negative trade at the population level. Note again the relationship between SIDS and sibling number in the table above. This is thus a standard safety vs. efficiency trade-off that we always face. It is always possible to do more to enhance the safety of children by increased spending on them in terms of both money (24/7 supervision vs. free range), child freedom (don't ever allow them out of the house), and parental time (drive children everywhere vs. let them walk/bike?). The cost of this is having fewer children. To give another example of this kind of trade-off, car seat regulations, Nickerson & Solomon 2024:

We show that laws mandating use of child car safety seats significantly reduce birth rates, as many cars cannot fit three child seats in the back seat. Women with two children younger than their state’s age mandate have a lower annual birth probability of .73 percentage points. This effect is limited to births of third children, households with access to a car, and households with a male present, where both front seats are likely to be occupied. We estimate that these laws prevented fatalities of 57 children in car crashes in 2017 but reduced total births by 8,000 that year and have decreased the total by 145,000 since 1980.

I won't be objecting when my fiancée sleeps with the baby because this is nicer for both of them.

It is silly, from a risk perspective.

A good dig here.

The doctors will also admit they have no idea what causes it. That means just be good to your kid and dont worry more than standard one (food, sleep, poop.)

Good call.

It's worth it if your fiancee gets more *sleep*.

Trust me on this.