Can we boost fertility with paid leave?

Maybe?

In every country some women get pregnant and give birth from time to time, and there is some kind of social support system in place for taking care of the not very capable mothers shortly before and after birth, as well as their relatively helpless offspring. Traditionally, this involved a man providing resources in exchange for sex and children scheme (we call it pair bonding). Later on, societies started making formal rules (laws), and pair bonding got upgraded to its legal version, marriage. The husband's role is the same though but there were now laws regulating how much support husbands are obligated to give etc. In recent history, some countries went from a system where relatives take care of their own and those without (useful) relatives die of hunger or cold, to a system where charities take care of those who cannot take care of themselves, to finally a system where a collaboratively sponsored group (the state) takes care of those who cannot or won't take care of themselves (whether they are mothers, sick, or old). In this expanded system (the welfare state), the state often provides some kind of monetary support for mothers during the perinatal period, but how much and under what conditions varies between states and over time, and may even include the fathers. Since pregnancy and birth and child rearing is so much work and it ultimately benefits everyone (by bringing in future taxes to sponsor public goods) not merely the parents (or their selfish genes), it makes sense for the state to encourage the fertility rates, and so as societies got wealthier and more childless, states starting doing more of this supporting. One important type of support is called paid parental leave where the state will pay perinatal mothers and maybe fathers for some duration. The amount paid may be fixed or may depend on their economic characteristics.

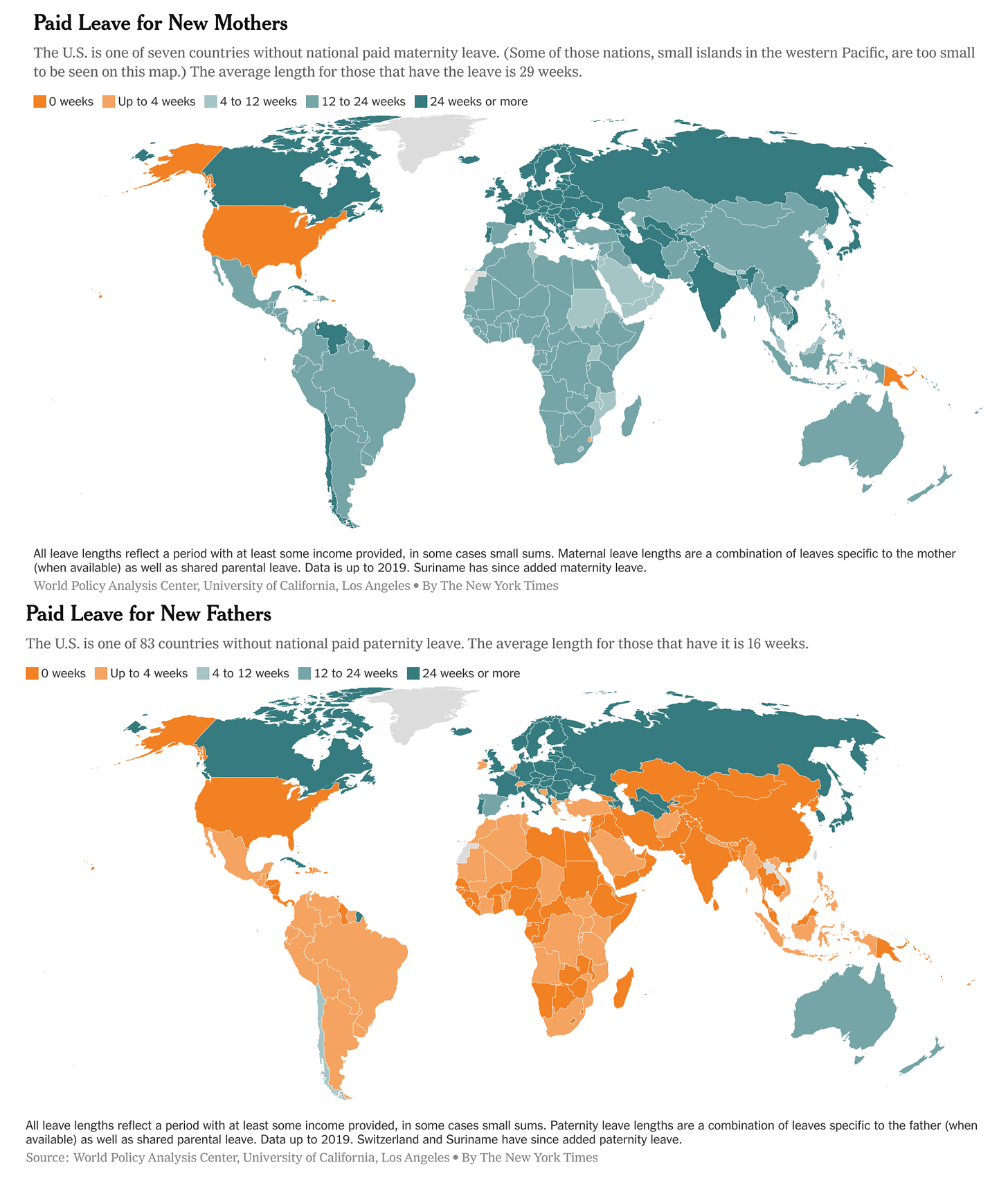

So do these policies actually work for increasing the fertility rates? Your first inclination would probably be to compare countries with and without those policies in their fertility rates, but this might make you rather disappointed.

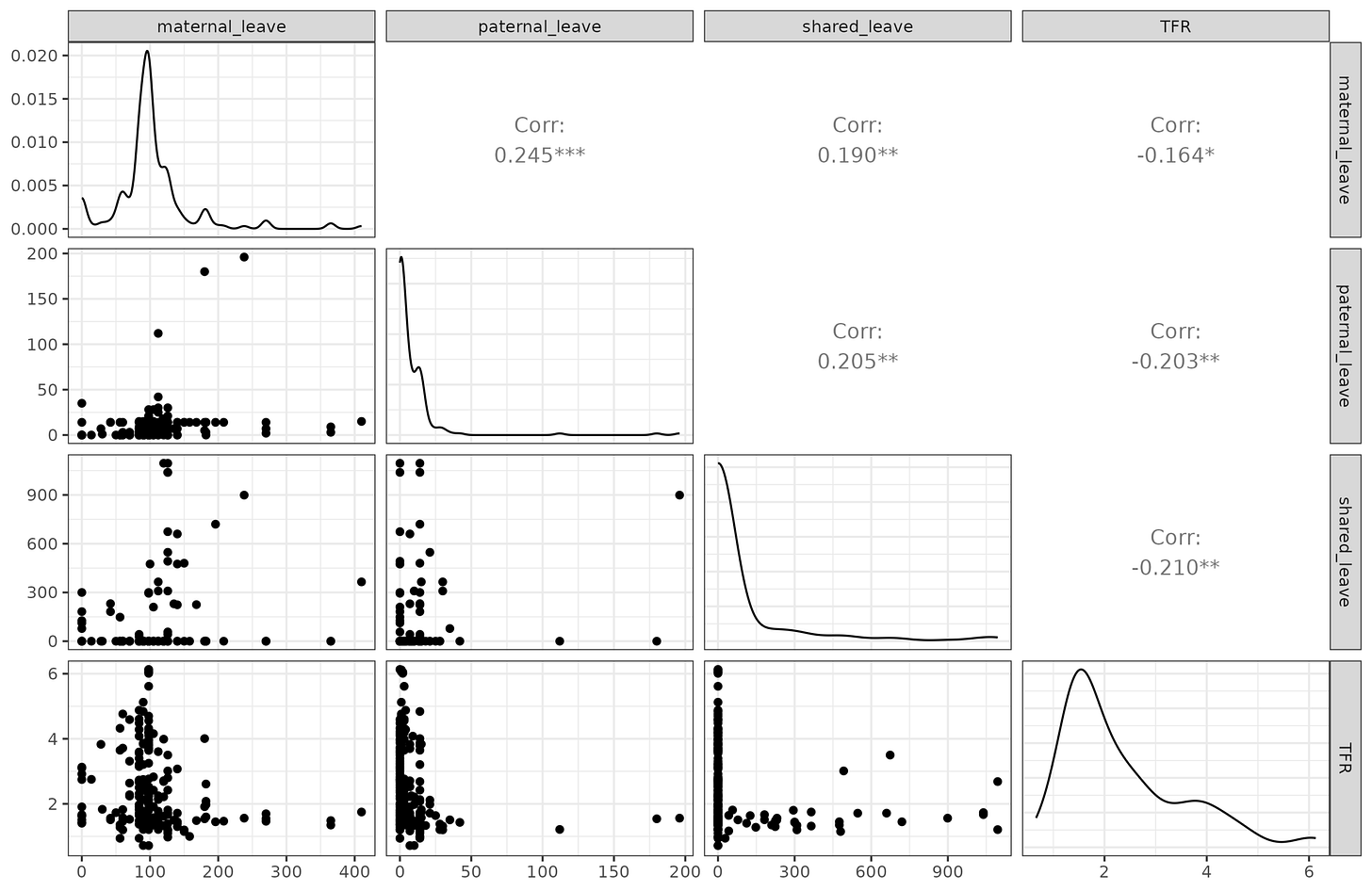

If you are vaguely familiar with the world map of anything, you know that the countries with less paid leave are those with worse (almost) everything but higher fertility rates. So sure enough, if we draw scatter plots, we can see this:

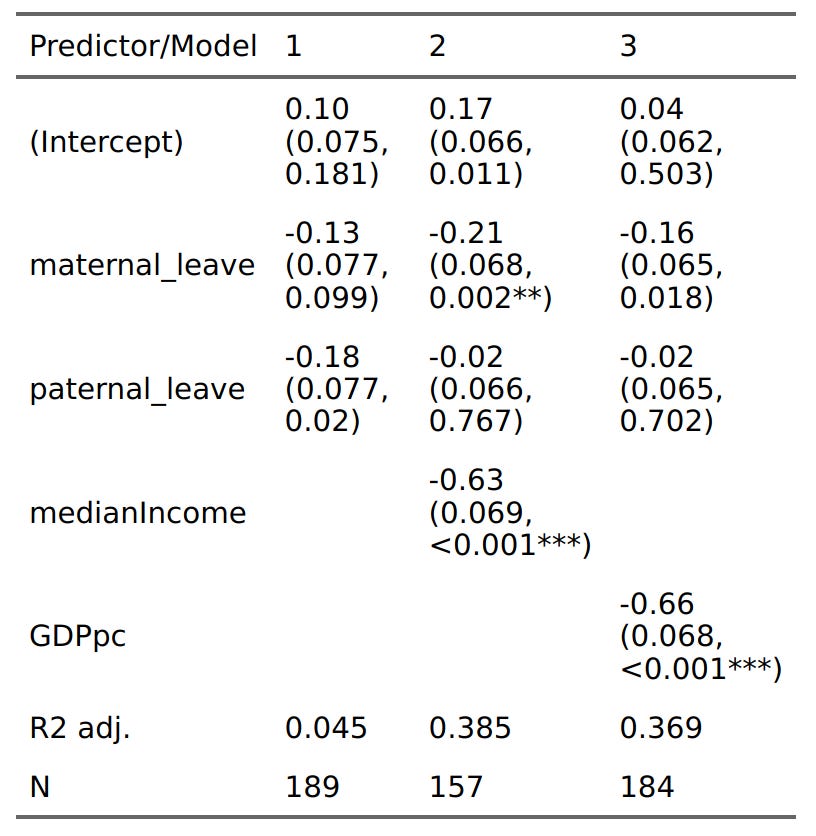

The correlations of all types of leave (shared, maternal, paternal) with total fertility rate are negative (but also recall that total fertility rate is a problematic estimate of actual completed fertility rate). While one could be tempted to draw the conclusion that actually state subsidies for having babies give you fewer babies, this would be unwise. Wiser would be to recognize that wealthier countries would implement more such welfare as part of their welfare state. From this perspective, we should control for wealth. I am going to use my preferred metric, median income, as this best reflects the money available to the most representative person in the country. Doing so gives us some regression model results:

The first model with just maternal and paternal leave tells us that maybe paternal leave is bad (p=2%). When we add either median income or GDPpc as a control, this effect goes away. However, we find instead that paid maternal leave is ... bad (p=0.2% and 2%), which is not what we expected. So maybe we need to keep adding covariates in a causally justified manner hope that the desired coefficient appears with a small p value.

But maybe it is better to try something more causally informative. There are a variety of other methods for inferring causality: 1) randomized trials, 2) regression discontinuity design, 3) natural experiments, 4) differences in differences. I am not aware of any country running an actual randomized trial for this unfortunately, but countries have changed their policies many times, so it should be possible to look for any breaks in ongoing trends near these policy changes. Ideally, a regression discontinuity study looks like this:

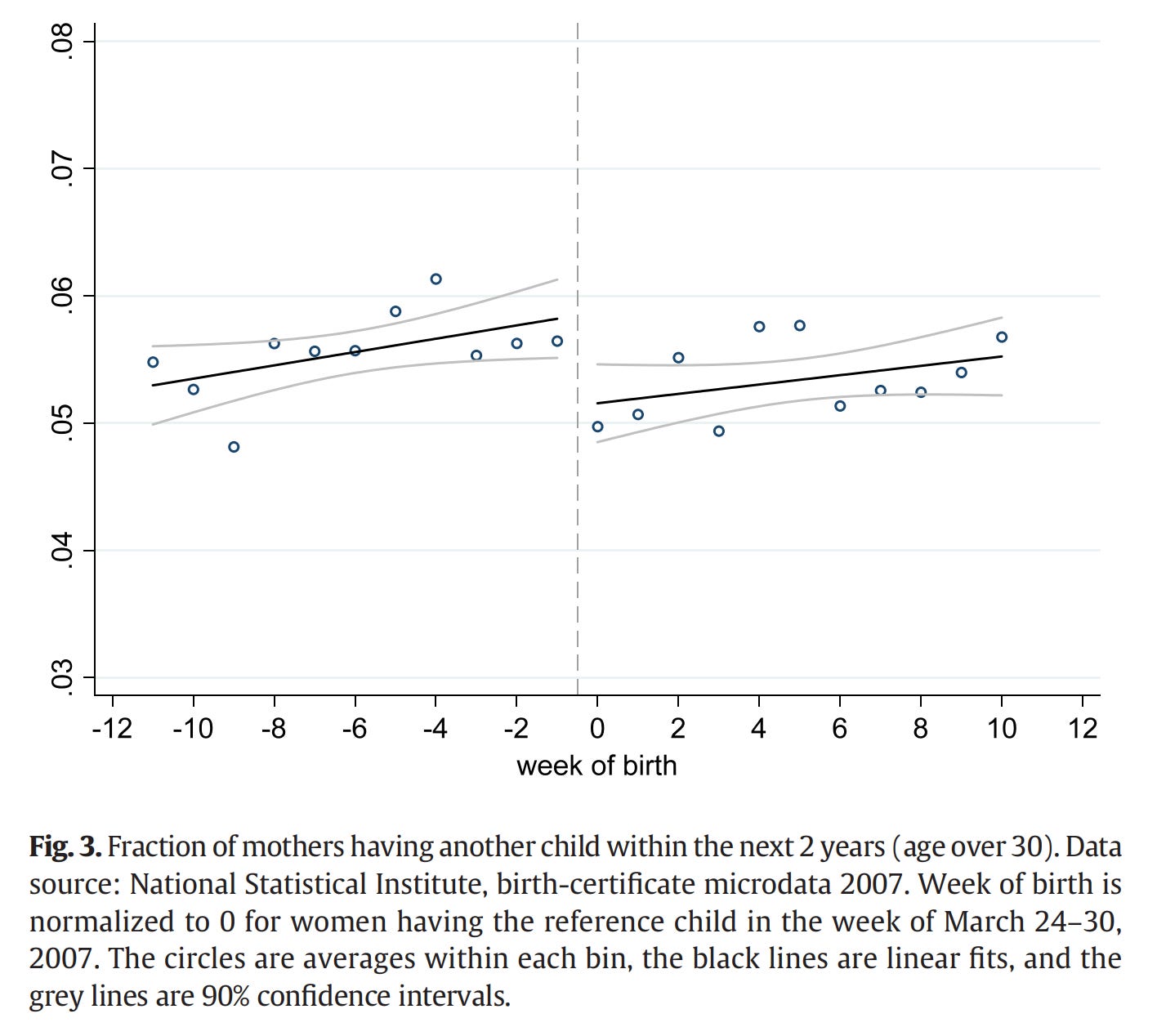

However, in real life datasets, the data are not usually this clear. Nevertheless, many economists and others have looked at such policy changes using regression discontinuity designs (RDD). One amusing study is:

Farré, L., & González, L. (2019). Does paternity leave reduce fertility?. Journal of Public Economics, 172, 52-66.

We find that the introduction of two weeks of paid paternity leave in Spain in 2007 led to delays in subsequent fertility. Following a regression discontinuity design and using rich administrative data, we show that parents who were (just) entitled to the new paternity leave took longer to have another child compared to (just) ineligible parents. We also show that older eligible couples were less likely to have an additional child within the following six years after the introduction of the reform. We provide evidence in support of two potentially complementary channels behind the negative effects on subsequent fertility. First, fathers' increasing involvement in childcare led to higher labor force attachment among mothers. This may have raised the opportunity cost of an additional child. We also find that men reported lower desired fertility after the reform, possibly due to their increased awareness of the costs of childrearing, or to a shift in preferences from child quantity to quality.

It looks reasonable enough insofar as RDD studies go. This result is unsurprising from an evolutionary psychology perspective. By forcing men into an maternal role, this conflicts with evolved adaptations concerning the division of labor and may cause relationship conflicts. On the other hand, paid maternity leave may work from the same perspective, so an interaction by sex is expected. So what do other studies show?

Thomas, J., Rowe, F., Williamson, P., & Lin, E. S. (2022). The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 1-16.

Low fertility is set to worsen economic problems in many developed countries, and maternity, paternity, and parental leave have emerged as key pro-natal policies. Gender inequity in the balance of domestic and formal work has been identified as a key driver of low fertility, and leave can potentially equalise this balance and thereby promote fertility. However, the literature contends that evidence for the effect of leave on fertility is mixed. We conduct the first systematic review on this topic. By applying a rigorous search protocol, we identify and review empirical studies that quantify the impact of leave policies on fertility. We focus on experimental or quasi-experimental studies that can identify causal effects. We identify 11 papers published between 2009 and 2019, evaluating 23 policy changes across Europe and North America from 1977 to 2009. Results are a mixture of positive, negative, and null impacts on fertility. To explain these apparent inconsistencies, we extend the conceptual framework of Lalive and Zweimüller (2009), which decomposes the total effect of leave on fertility into the “current-child” and “future-child” effects. We decompose these into effects on women at different birth orders, and specify types of study design to identify each effect. We classify the 23 studies in terms of the type of effect identified, revealing that all the negative or null studies identify the current-child effect, and all the positive studies identify the future-child or total effect. Since the future-child and total effects are more important for promoting aggregate fertility, our findings show that leave does in fact increase fertility when benefit increases are generous. Furthermore, our extensions to Lalive and Zweimüller’s conceptual framework provide a more sophisticated way of understanding and classifying the effects of pro-natal policies on fertility. Additionally, we propose ways to adapt the ROBINS-I tool for evaluating risk of bias in pro-natal policy studies.

Overall, the evidence is not so satisfactory and the synthesis is not good either (no real quantitative meta-analysis) and only using some post-hoc groupings do these authors make a case for paid leave having positive effects. Most of the studies concern a few Scandinavian countries changing their policies, presumably since they have the best data to study the question with (register data), and because Scandinavians produce a lot more science in general.

One study is worth highlighting though:

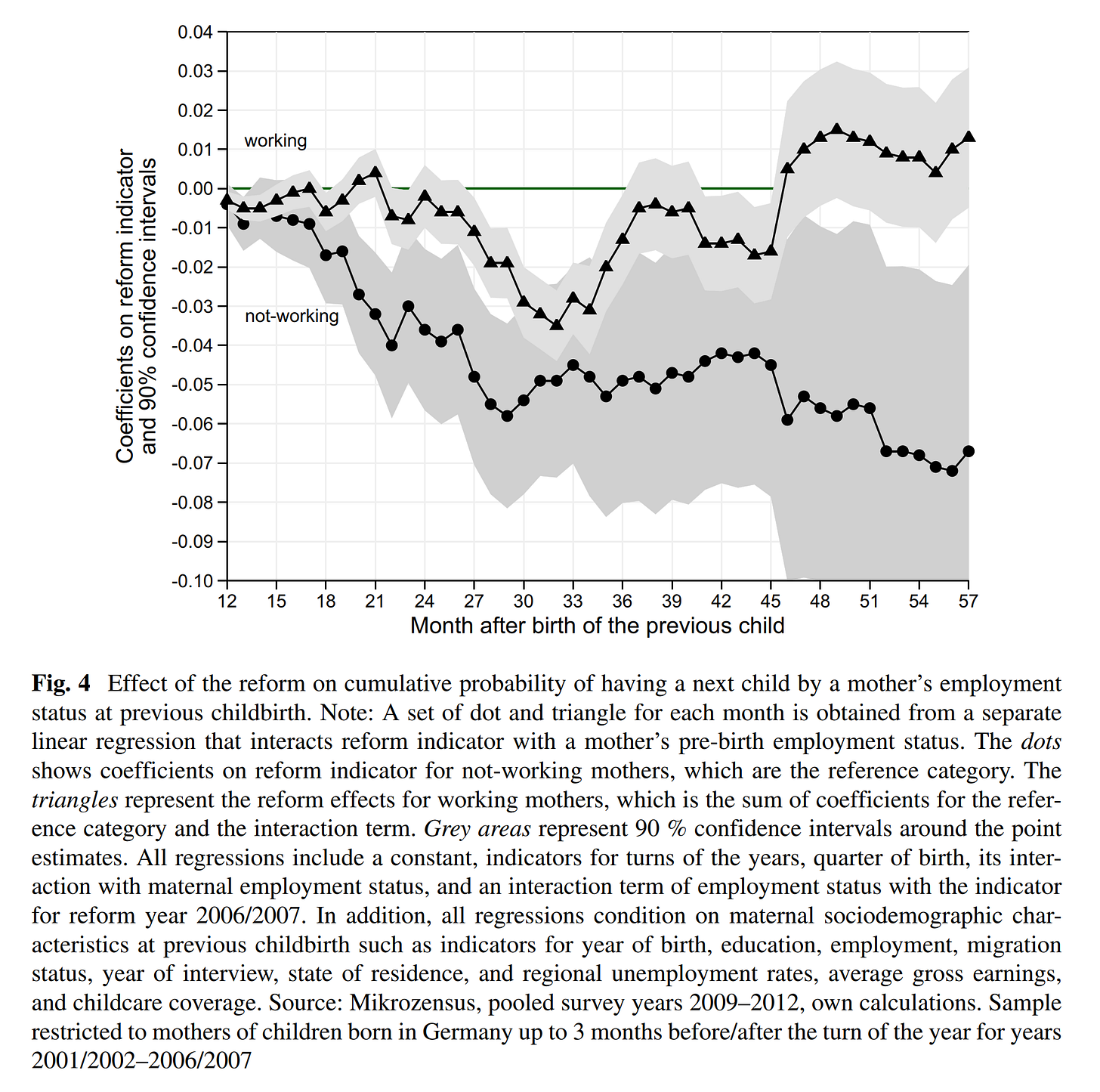

Cygan-Rehm, K. (2016). Parental leave benefit and differential fertility responses: Evidence from a German reform. Journal of Population Economics, 29, 73-103.

This paper examines the causal effects of a major change in the German parental leave benefit scheme on fertility. I use the unanticipated reform of 2007 to assess how a move from a means tested to an earnings-related benefit affects higher-order births. By using data from the Mikrozensus, I find that the reform significantly affected the timing of higher-order births in the first 5 years after a last birth. Overall, mothers “just” eligible for the new benefit for the current birth initially reduce subsequent childbearing and extend birth spacing, compared to mothers “just” ineligible. However, by the end of the third year, mothers start to compensate for the earlier losses. The negative effects are largely driven by the low-income mothers, who are now worse-off and do not display any catch-up effects. The differential fertility responses along the income distribution are in line with the heterogeneous structure of the economic incentives.

In a figure:

Because the payout in the new system depended on the earnings of the mother in the period before the birth, high-income mothers would get quite generous payouts and low or no income mothers would get the minimum. This had a clear eugenic effect since the reduced payouts for the low income women reduced their future fertility, though this came at the cost of the total fertility rate declining a bit. It's an example of the quantity-quality trade-off in boosting fertility -- a reform that increases fertility usually increases the dysgenic fertility pattern, and vice versa.

My impression of the research is that it is not clear that paid leave (parental leave) increases fertility overall. Paternal leave may decrease fertility even. Primitive regression models suggested a negative effect, even controlling for wealth. It's disturbing and pathetic that even though the developed world has had a below replacement fertility rate for 50 years, we still don't even know if some of our most expensive policies to increase fertility even work at all.

We don’t know what works because “what works” would just be *massive* payroll tax breaks to married couples with children. Enough that the childless would truly be paying their fair share towards their own retirement benefits.

It wouldn’t cost society but it would be a very expensive way to buy votes because children can’t vote and olds vote at high rates. Also the people who would like it (married families with income) probably wouldn’t move enough further to the right for the amount it would “cost” in the short run (which is all that matters in politics).

So we get smaller benefits tied to some kind of grift or culture war signal or to poor single mothers because the votes are cheaper and have an easier to digest cover story.

Even Hungary can’t manage to have “married filing jointly” as a tax concept.

South Korea could solve their fertility problems tomorrow if they would pass a law that all women who don't have 2 kids by age 28 get conscripted for 2 years like men are.