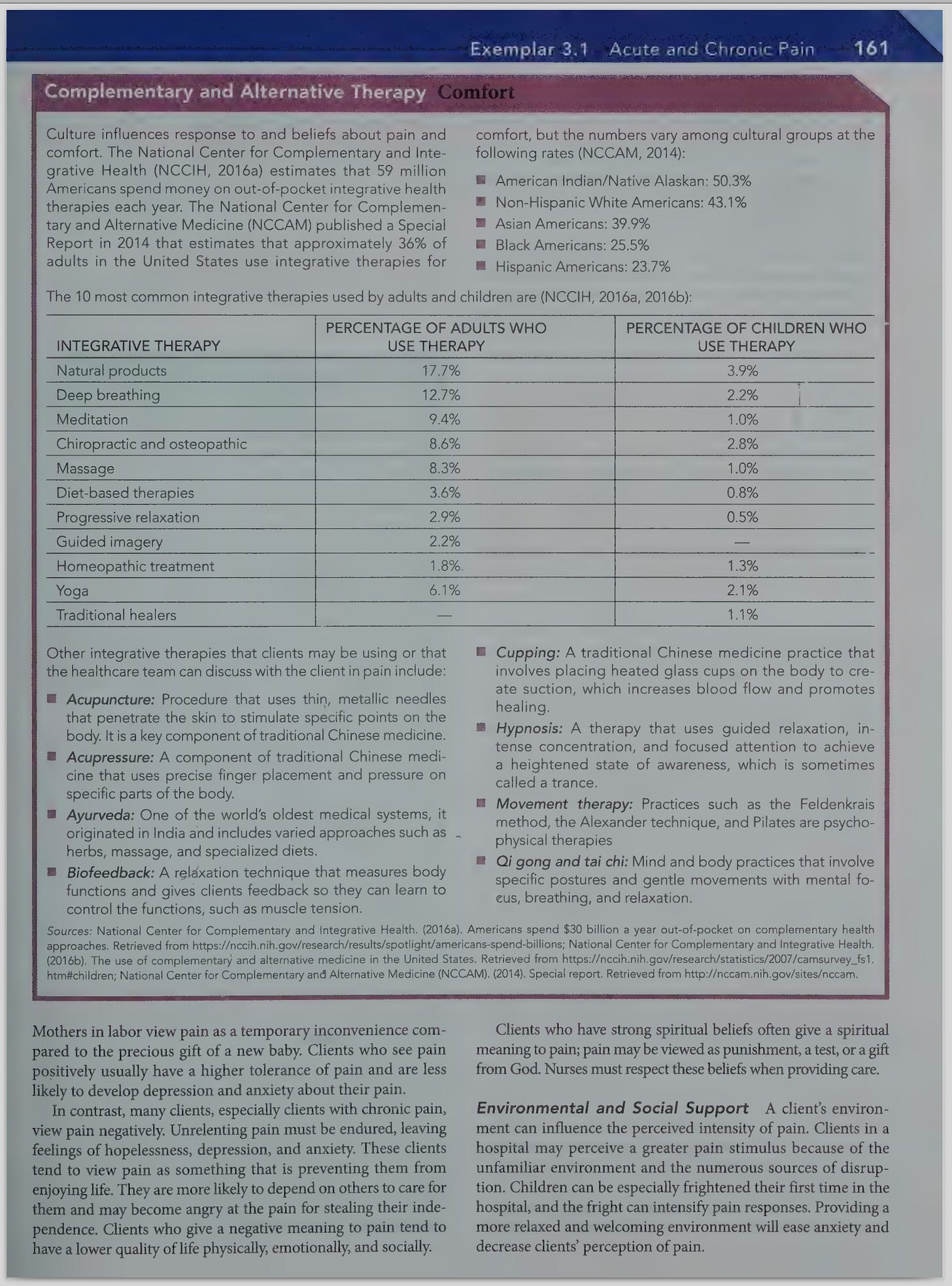

"Cultural Differences in Response to Pain" revisited

Also surprise communist traitor

I was sent this viral image about ethnicity and pain management:

Tracing the source of this, it comes from a 2017 blogpost, which cites an article in NYPost. The complaints seem to be due to a crazy person on old Twitter:

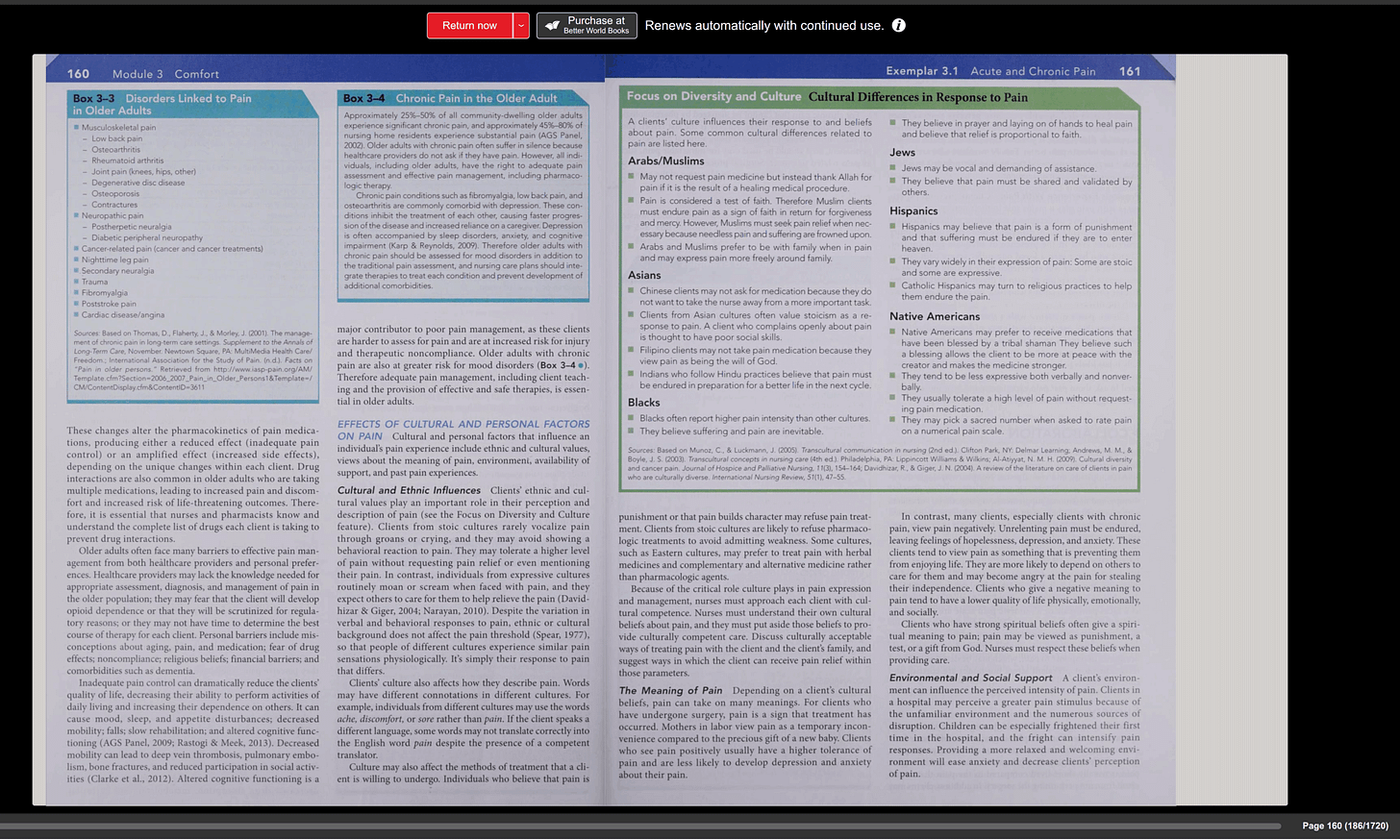

Nevertheless, when I posted it on my account, some people expressed doubt it was real. That’s when I found the above 2017 posts. Nevertheless, these could still be fake. So I downloaded the book. It turns out it is volume 1 out of 3, and the newspaper claims it is the 2nd edition. However, when I downloaded the second edition and looked, it’s not there:

The content and style matches, and other pages have green “Focus on Diversity and Culture” boxes, just not that one. I checked the 1st edition but it looks much different and the page contents don’t match. 3rd edition was published after the 2017 news, so cannot be the right book.

So it is fake? Talking to the AI, it suggested there may be different printings which could have minor variation. Sure enough, the copy I had was the revised 2nd edition, which presumably means there is an unrevised 2nd edition. I managed to find a copy of this on Internet Archive, and it checks out:

So the meme was real. So what happened is probably due to the complaints, Pearson quickly revised a minimally modified 2nd edition, called the revised 2nd edition.

Anyway, since this is a science blog, let’s check the sources cited:

Muñoz, C., & Luckmann, J. (2005). Transcultural communication in nursing (2nd ed.). Clifton Park, NY: Thomson/Delmar Learning.

Andrews, M. M., & Boyle, J. S. (2003). Transcultural concepts in nursing care (4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Al-Atiyyat, N. M. H. (2009). Cultural diversity and cancer pain. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 11(3), 154–164.

Davidhizar, R., & Giger, J. N. (2004). A review of the literature on care of clients in pain who are culturally diverse. International Nursing Review, 51(1), 47–55.

I didn’t find anything of note regarding the Jewish quote in Muñoz, but it’s hard to know where to look in this 300+ page book since no page citation was given. Andrews has the same problem. However, the papers contain:

Al-Atiyyat says:

Numerous studies of whites,20-23 Japanese,24,25 Italians,4,26 Jews,4,27 Irish,4,28 African Americans,29-31 Chinese,25,32 Hispanics,33 Vietnamese,4,34 Indians,35 Arab Americans,36,37 and Arab patients 38-40 lend indirect support to the biocultural hypothesis of pain as related to various ethnic groups. The research findings support interethnic similarities and differences. When reviewing these studies, it is necessary for readers to avoid stereotyping patients and overgeneralizing their behaviors.The information merely helps nurses to become familiar with different responses to pain and with key areas of assessment. A number of the references cited are dated but are classic studies that represent pioneering research in culture and pain.

...

In the Arab-Islamic heritage, pain is not considered a divine punishment for sins but rather a test of faith. Therefore, Muslims are required to have patience and endure pain, as a sign of strong faith, in return for God’s mercy and forgiveness. However, Muslims are required to seek treatment and pain relief when necessary because needless pain and suffering are frowned upon,98 and many Christians stress seeking atonement and redemption.99 Religion evidently provides more than just a distraction from suffering. The social network and support provided by religions may be associated with lower pain levels, and religious belief may improve self-esteem and sense of purpose.100 Further research is needed on relations among pain, responses to management of pain, and individuals’ religious beliefs.

So the authors of the textbook quite clearly followed Al-Atiyyat’s words with regards to Arabs.

Davidhizar and Giger write:

In a classic study by Lipton & Marbach (1984), pain experiences of Black, Irish, Italian, Jewish, and Puerto Rican patients were assessed. These patients were randomized from 476 consecutive patientsseen in a facial pain clinic into 50 per ethnic group.Patients were grouped into six areas, socio-demographic background, social and culturalassimilation, level of psychological distress, history of pain symptom and treatment, and clinical diagnosis. All patients were interviewed by the same clinician in order to control bias during the presentation of questions and collection of patients’ responses. A 35-item scale was utilized to measure pain experience. No significant interethnic differences were found for 65% of the items with the majority of items indicating differences concerning the patients’ emotionality (stoicism vs. expressiveness) in response to pain and according to interference in family functioning attributed to pain. Black, Italian, and Jewish patients were the most similar concerning issues such as stoicism, expressiveness to pain, and daily functioning affected by pain.Duration of pain was a significant variable for the Italian patients. Other researchers have noted that Italian individuals may be unusually expressive and describe physical complaints in a dramatic manner (Koopman et al. 1984; Salerno 1995). Garro (1990) noted that Jewish and Italian clients were more vocal and demanding of assistance when in pain as compared to White clients. It is important for health care providers to appreciate both the verbal and physiological responses to pain in order to avoid misdiagnosis of having both pain and a hysterical emotional problem (Rotunno & McGoldrick 1996).

So the textbook authors were right to include this bit too.

For good measure, I checked the original study too, Linda Garro 1990. Garro says:

The majority of comparative studies have been done with ethnic groups in the context of urban North America. A seminal study carried out by Zborowski (83) in the early fifties examined how pain was expressed by Jewish, Italian, and “Old American” (defined as white, usually Protestant, and at least 3rd generation American) patients in ~ large New York City hospital. All individuals Interviewed were male World War II veterans.At the group level, Zborowski reported that the Jewish and Italian patients talked more about their pain, complained more about it, exhibited more vocal responses such as crying and groaning, and were more demanding of assistance while in pain than were the Old American patients who tended to hide their pain. Although similar reactions to pain characterized the Jewish and Italian patients, Zborowski argued that underlying attitudes and cultural meanings were different for the two groups. The Italian attitude is described as characterized by an orientation to the present. Italians focus on the immediacy of pain sensation and are primarily concerned with alleviation of pain. The Jewish attitude is depicted as future-oriented, with the key concern being the meaning and source of pain rather than the actual pain sensation. Jewish patients expressed a reluctance to take analgesic medication because of possible long-term health effects, such as drug addiction, and because the pain medication only treats the symptom and not the underlying disease. The Old-American attitude is also portrayed as future-oriented. But in contrast to the Jewish skepticism about medicine, Old Americans were described as optimistic about medical treatment because of a mechanistic view of the body as something which breaks down and can be fixed.

So it’s a rabbit hole. This is yet another review of a review of a review. So lets check the final study, Zborowski 1952:

Despite the close similarity between the manifest reactions among Jews and Italians, there seem to be differences in emphasis especially with regard to what the patient achieves by these reactions and as to the specific manifestations of these reactions in the various social settings. For instance, they differ in their behavior at home and in the hospital. The Italian husband, who is aware of his role as an adult male, tends to avoid verbal complaining at home, leaving this type of behavior to the women.In the hospital, where he is less concerned with his role as a male, he tends to be more verbal and more emotional. The Jewish patient, on the contrary, seems to be more calm in the hospital than at home. Traditionally the Jewish male does not emphasize his masculinity through such traits as stoicism, and he does not equate verbal complaints with weakness. Moreover, the Jewish culture allows the patient to be demanding and complaining. Therefore, he tends more to use his pain in order to control interpersonal relationships within the family. Though similar use of pain to manipulate the relationships between members of the family may bepresent also in some other cultures it seems that in the Jewish culture this 23is not disapproved, while in others it is. In the hospital one can also distinguish variations in the reactive patterns among Jews and Italians. Upon his admission to the hospital and in the presence of the doctor the Jewish patient tends to complain, ask for help, be emotional even to the point of crying. However, as SOOR as he feels that adequate care is given to him he becomes more restrained. This suggests that the display of pain reaction serves less as an indication of the amount of pain experienced than as a means to create an atmosphere and setting in which the pathological causes of pain will be best taken care of. The Italian patient, on the other hand, seems to be less concerned with setting up a favorable situation for treatment. He takes for granted that adequate care will be given to him, and in the presence of the doctor he seems to be somewhat calmer than the Jewish patient. The mere presence of the doctor reassures the Italian patient, while the skepticism of the Jewish patient limits the reassuring role of the physician.

It’s not a quantitative study, but rather ethnographic based on doctors’ impressions.

But there’s more. The author is Mark Zborowski, and he turns out to be a very colorful person too:

Mark Zborowski (27 January 1908 – 30 April 1990) (AKA “Marc” Zborowski or Etienne) was an anthropologist and an NKVD agent (Venona codenames TULIP and KANT[1]). He was the NKVD’s most valuable mole inside the Trotskyist organization in Paris during the 1930s and in New York during the 1940s.[2][3][4]

He was himself Jewish, so it’s hard to complain about hostile ethnic stereotyping in his pain study. He was also hilariously a turncoat communist spy, spying against the Trotskyists for the Soviets. He was in fact instrumental in the death of Trotsky, as he became the head of the Troyskyist faction in Paris, after being involved in multiple murders as a spy.

So there we have the full story!

Jewish communist traitor helps get Leon Trotsky assassinated.

Eventually becomes an anthropologist and studies ethnic/cultural differences in pain.

His classic paper from 1950 ends up getting cited in review articles, which piggyback on each other.

The last such review is a nursing textbook, which some also Jewish woman on Twitter complains about.

I spent 27 years as an ER doctor. Canada, Japan, and the USA. There ARE cultural differences in response to pain. In my experience, the greatest response to pain is seen in American Blacks and Hispanics, the least in Native Canadians - and it's learned early. Let me give you just one typical example from my experience:

Native Canadian boy age 2 cuts his forearm, needs stitches. Any other culture, I'd have had a nurse hold him down for the procedure, because if he were White, Black, or Hispanic he'd cry and struggle. Not that Native boy. He held still, face showing no emotion throughout the whole procedure. NEVER seen that in any other culture.

I suspect that the Inuit show the least response of all, but I only treated a handful so can't say for sure.

"You can ignore reality, but you can't ignore the effects of ignoring reality" - Fred Reed.

I shook the hand of an old NYC Jewish left-winger who had hung out with Trotsky in Mexico and had photos to prove it.

Which was just as well because after Mexico he joined the Spanish Revolution and was picked up as soon as he crossed the border and about to be shot as a spy.

Not knowing the side or faction of his would-be executioners he took a chance and pulled out the Sacred Photograph and his captors went apeshit and carried on their shoulders back to their squalid camp.

The guy was fearless, always looking for worthy cause to fight for.