Effective Africanism

Against applied utilitarianism

In moral philosophy, there's a variety of competing theories of normative morality. Normative meaning actual claims about what is good and bad, and what actions are correct and which are immoral. This is opposed to descriptive theories, where essentially are a branch of psychology trying to explain how humans make moral judgements. The latter is a branch of science and doesn't even assume that there are right and wrong actions in any philosophical sense. In fact, research into the origins of human morality provide evidence that there isn't such a thing, or maybe more cautiously, that there isn't any good reason to accept such claims.

Assuming for the sake of argument that some moral claims are true in some philosophical sense (moral realism), which approach to morality is true? There are many contenders. From the ancient Greeks we have virtue ethics. There's deontology, law-like ethics systems, mainly represented by the German Immanuel Kant (Germans being famous for their love of laws), but Abrahamic religions also have a law-like approach, using sets of commandments as well as 100s of other rules. Various versions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam) and their variaties (denominations, sects, branches) of Abrahamic religions try to interpret these in some consistent fashion. For instance, Catholics have doubled down on contraception being immoral based on their reading of the story of Onan, whereas Protestants don't care much, at least in modern times. Finally, we have the most modern system of morality, consequentialism, chiefly under the name of utilitarianism. This comes from the British, mainly Jeremy Bentham (1789) and John Stuart Mill (1861). In this approach, judging an action consists of judging whether it leads to good consequences, or whether it fits some class of actions that in general lead to good consequences (rule utilitarianism to avoid outcome bias). Rule utilitarianism is not so far from Kant's categorical imperative, though the justifications are much different.

My reading of moral philosophy is that virtue and deontology ethics are hopeless in practice as no one can agree on any ranking of these rules and virtues, so when they conflict, there is no way to decide. Multi-dimensional optimization problems require weights and trade-offs. In consequentialism, the problem of ranking of different goods is faced head-on, much like an economist would do. Unsurprisingly, it was also the British who advanced economic thinking around the same time. I agree with Joshua Greene, when he wrote in his dissertation (The Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Truth about Morality and What to Do About it):

In the last section I explained why deontological talk is likely to fail in a psychologically informed, anti-realist environment. Once we’ve put some distance between ourselves and our intuitions, once we know where our intuitions come from and understand that they are not messengers of moral truth, drawing deontological moral lines and expecting others whose inclinations are otherwise to respect those lines just seems silly. And with deontology and the realism it reflects discredited, the utilitarian approach is, I claim, simply what’s left. Nearly everyone is a utilitarian to some extent. Nearly everyone agrees that all other things being equal raising someone’s level of happiness, either your own or someone else’s, is a good thing, and that lowering someone’s happiness is a bad thing.

Utilitarianism with its mathematical framework is the only moral system with some semblance of modern rationality. Greene goes on:

To a connoisseur of normative moral theories, nothing says “outmoded and ridiculous” quite like utilitarianism. This view is so widely reviled because it has something for everyone to hate. If you love honesty, you can hate utilitarianism for telling you to lie. If you think that life is sacred, you can hate utilitarianism for telling you to kill the dying, the sick, the unborn, and even the newborn, and on top of that you can hate it for telling you in the same breath that you may not be allowed to eat meat (Singer, 1979). If you think it reasonable to provide a nice life for yourself and your family, you can hate utilitarianism for telling you to give up nearly everything you’ve got to provide for total strangers (Singer, 1972; Unger, 1996), including your own life, should a peculiar monster with a taste for human flesh have a sufficiently strong desire to eat you (Nozick, 1974). If you hate doing awful things to people, you can hate utilitarianism for telling you to kidnap people and steal their organs (Thomson, 1986). If you see the attainment of a high quality of life for all of humanity as a reasonable goal, you can hate utilitarianism for suggesting that a world full people whose lives are barely worth living may be an even better goal (Parfit, 1984). If you love equality, you can hate utilitarianism for making the downtrodden worse off in order to make the well off even better off (Rawls, 1971). If it’s important to you that your experiences be genuine, you can hate utilitarianism for telling you that no matter how good your life is, you would be better off with your brain hooked up to a machine that gives you unnaturally pleasant artificial experiences. No matter what you value most, your values will eventually conflict with the utilitarian’s principle of greatest good and, if he has his way, be crushed by it.26 Utilitarianism is a philosophy that only... well, only a utilitarian could love.

As as matter of fact, the point of this post is to add another issue to this list, one with practical implications as opposed to the merely theoretical (despite the trolley problems, no one has been sacrificing fat people off bridges yet). The chief utilitarian-rationalist charity organization today is GiveWell. Their team of analysts try to figure out which kind of charity is the most effective at saving lives. Effective Altruism being the name of the game. Given that it is usually easier to save lives in poor places, meaning mainly in Africa, this means that most of their top charities are just trying to keep more Africans alive. We can verify this by having a look at their current top charities:

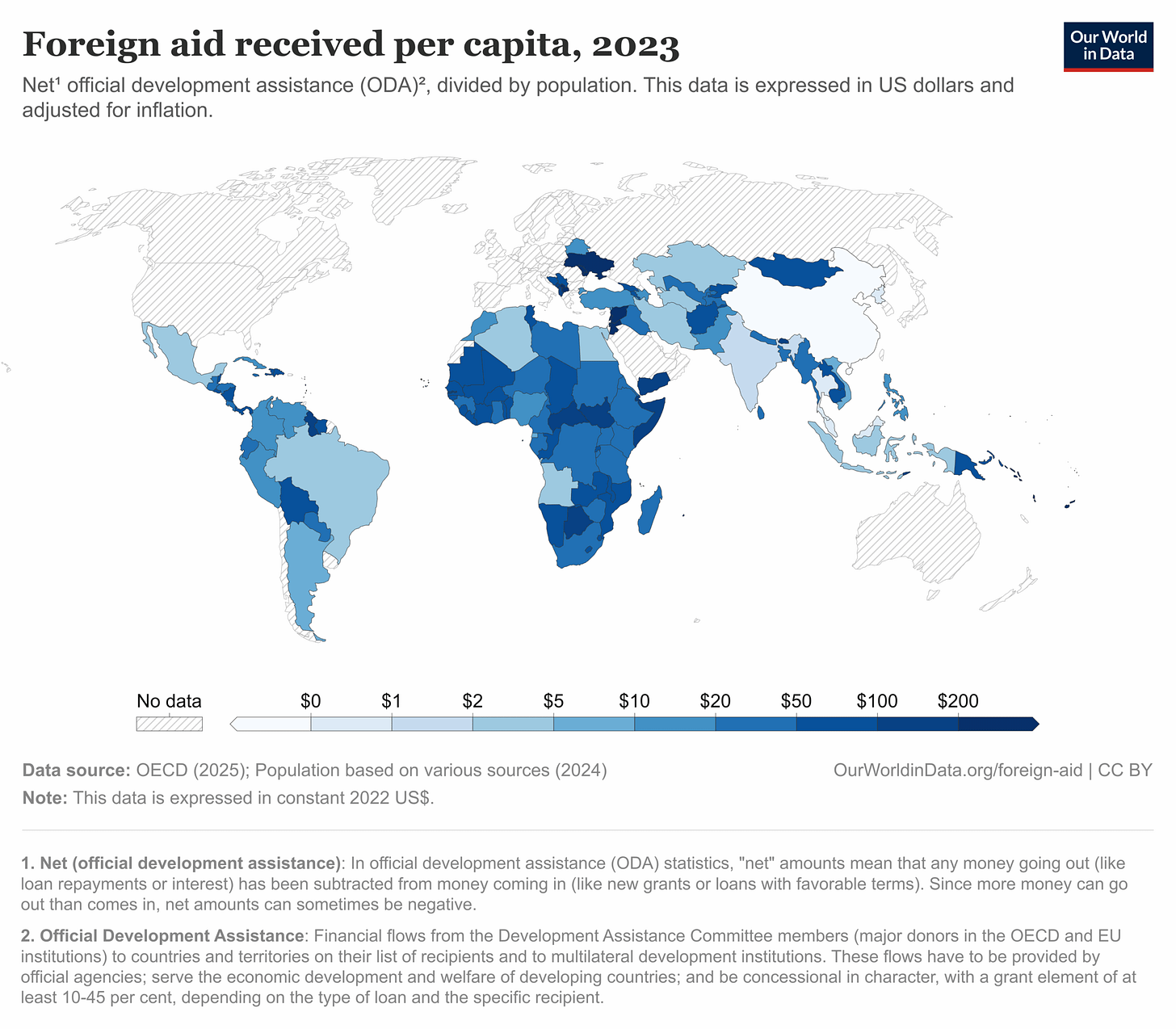

And indeed, 4 or maybe 5 of their 5 photos feature Africans. Of the 4 charities mentioned, 3 of them specifically mention Africa as their target. I looked into the Vitamin A charity and it operates in Bangladesh. These are laudable humanitarian goals. However, they don't do anything to further humanity's long-term interests. Progress depends on technology and scientific advances. These efforts are not helped by saving the lives of people in the third world. So while the movement behind these initiatives is broadly called Effective Altruism, one might more aptly call it Effective Africanism. Since Africans keep being poor and keep multiplying, these projects will have to keep scaling up. If African fertility rates keep being higher than everybody else's, the end result of this applied morality is Africanmaxxing. It is hard to see how this leads to the world becoming a better place given that Africans are the least capable group of advancing science and technology, and human flourishing more generally.

Finally, I couldn't think of a good way to include this quote in context, so I am putting it at the bottom (also from Greene):

“Utilitarian: one who believes that the morally right action is the one with the best consequences, so far as the distribution of happiness is concerned; a creature generally believed to be endowed with the propensity to ignore their [sic] own drowning children in order to push buttons which will cause mild sexual gratification in a warehouse full of rabbits”.

"There isn't any good reason to believe anything is morally wrong, so here is a reason why X is morally wrong."

The only honest effective altruist would end up somewhere near what Elon Musk is doing (on some things).

1) Spread his superior genes as far as wide as possible and utilizing the latest genetic enhancement at his disposal.

In theory he should take it further, buying eggs and using surrogates to do mass breeding programs and raising them in orphanages. But the PR impact of that is probably too much for him (just paying willing sluts millions to have IVF babies with him already causes a lot of backlash).

2) Donate nothing to charity and try to obtain high ROI for your capital. To the extent that your personal involvement can raise the ROI, dedicate your life to that.

Of course if you want something obviously correct from an EA perspective but within the mainstream, smart people should just have as many kids as they can afford and invest any spare capital they have in index funds.