EU health tech at its finest: case study of Oviva

Paperwork innovation vs. technology

A friend sent me this linkedin post some days ago. I was mainly interested because I thought it might have something to do with making eggs for IVF (oviva meaning egg:

200M USD for a healthcare startup in Germany? Sounds fishy. Let’s check out their website:

It’s basically just an app that tells you what to eat and so on. All of their pictures show overweight White women. Their selling points list:

This is translated from German, but it’s pretty funny that the most important, top of the list point is that customers don’t pay for it directly, healthcare insurance covers it. Then it’s “proven by study”, and naturally no stressful working methods (eat fewer calories/don’t eat candy). So by now we get an idea of how this setup works:

Make a generic health advice app. The advice can be personalized (the advice is always the same, eat less calories), and you can get some dietitians in on the scheme. You could just automate this with LLMs though. Also some recipes (recall, women in the photos).

Get some scientists to produce studies showing support.

Spend money to lobby the health insurance companies to consider this a kind of healthcare.

Then just sign up millions of people for infinite free money. Customers won’t object much because the money isn’t coming from them directly, but their healthcare insurances. Of course, ultimately they do pay for it in higher healthcare insurance fees, but this is a socialized cost/negative externality situation.

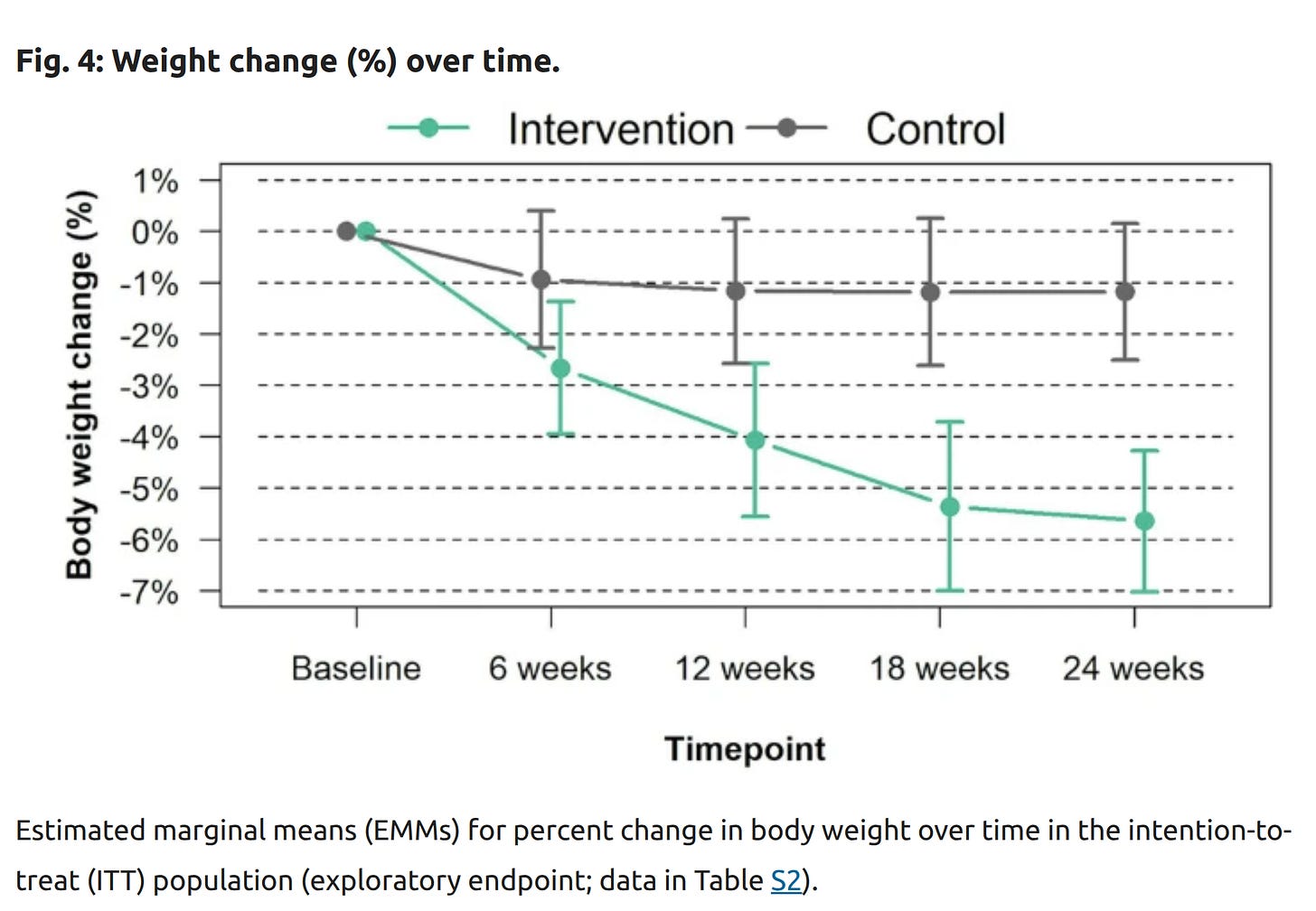

Helpfully, they list all their studies on the website, so let’s have a look. Though there’s like 30 publications, there’s really only one trial, a real randomized clinical trial (RCT). They have been salami publishing it, but the results are just these:

The p values are fine. The study had a lot of drop-outs but in both control and treatment groups, but it didn’t look too suspicious to me. The study used the waiting list cross-over design, that is:

This study was a prospective decentralized randomized controlled trial with technology-enabled, remote recruitment, care delivery, and data collection conducted in Germany. The study’s primary endpoint was defined as the change in body weight assessed at 6 months of intervention. The study had a crossover design with participants in the intervention group continuing to receive the intervention for an additional 6 months (after primary endpoint assessment), whilst participants in the control group waited to receive the intervention for 6 months and then received the intervention for 6 months. Further analyses are planned for both 48 and 96 weeks.

This is a good design. So we can be reasonably confident that people using some app that monitoring their eating habits cause them to think more about eating less, so they lose a bit of weight. Mind you that the average BMI in the study was 38 (mean age 45), severely obese middle aged people. The people on the wait list lost about 2% body weight, and those using this app lost about 5.5, thus the extra loss was about 3.5%point after 6 months. “proven by study” indeed!

One can make an economic argument that healthcare insurance should cover this treatment. After all, it usually covers the GLP drugs that do the same thing but much more effectively. However, they are also more expensive (for now), well, maybe. Since Oviva handles the paperwork themselves, the price of their app isn’t actually shown anywhere and AI couldn’t find it either. It may thus be rather pricy, and maybe not even much better than the price of the drugs. Anyway, the question from an economic perspective is whether the cost of this treatment is best borne by the end-users themselves, or whether it should be included in the health insurance coverage. Since obesity causes all kinds of medical problems that are otherwise covered (diabetes, hypertension, heart failure etc.), it makes sense to fix the cause of these problems earlier than wait for them to occur and then pay for the more expensive treatment. Of course, given LLMs, making such an app and making it provide personalized advice is now a trivial problem that [current best AI] can probably write in a few hours. The real business trick here is getting the health insurance to pay for this, and they will no doubt make use of the above economic argument.

Still, what do they need 200M for? That’s a lot of money for growing an already finished app. It turns out that they also raised 80M in 2021 (series C). They note that round C is a cumulative investment of $115m (seed+A+B+C), thus the additional 200M brings the total to 315M USD. That’s a staggering amount of money to build a simple app. Thus, I imagine that most of this money has been spent on lawyers doing the lobbying and paperwork. I think this thus provides an excellent comparison to the typical American tech startups, which usually produce products for the private sector, and the money goes towards developing the product not mainly to lawyers or lobbyists.

Great investigative breakdown. The fact that raising €200M for what's basically a diet tracking app does sound fishy until you realize most of it probaby went to lobbying and paperwork, not tech development. The contrast with US startups that dump funding into actual product innovation is pretty stark. I've noticed this patern with lots of European "healthtech" where the business model is regulatory capture first, technology second.

As a software engineer, the biggest problem I see in European startups is adverse selection. Most of the genuinely capable and brilliant entrepreneurs will attempt to get YCombinator seed stage funding, there is just nothing remotely close in terms of quality and prestige in Europe. Once you're in, you might as well rebase to San Francisco or elsewhere in the US for the massive network and talent pool that just got opened to you. You're kind of seeing the effects of this here.