Garett Jones finishes his trilogy

Beating around the bush, but maybe effectively so

In the last 10 years, economist Garett Jones has been writing a series of books, a trilogy to be exact:

Jones says in the post-script:

THIS IS THE FINAL BOOK IN my Singapore Trilogy. The trilogy began with Hive Mind, where the first country mentioned is Singapore, a nation that unsurprisingly combines high test scores, high average incomes, and high-quality governance. The second book, 10% Less Democracy, has an entire chapter on the lessons the world’s rich democracies can learn from Singapore, a nation with perhaps 50 percent less democracy than the U.S. And of course, Singapore—largely a nation of immigrants whose ancestors left southern China—illustrates cultural transplant theory.

As it happens, I have already reviewed the first two, and I finally got around to reading the last one, The Cultural Transplant. The table of contents is:

PREFACE: The Best Immigration Policy

INTRODUCTION: How Economists Learned the Power of Culture

1. The Assimilation Myth

2. Prosperity Migrates

3. Places or Peoples?

4. The Migration of Good Government

5. Our Diversity Is Our _____

6. The I-7

7. The Chinese Diaspora: Building the Capitalist Road

8. The Deep Roots across the Fifty United States

Je ne sais quoi

CONCLUSION: The Goose and the Golden Eggs

The book is materially much the same as We Wanted Workers by George Borjas (Jason Richwine's advisor) which I also reviewed some years ago too. One way to think about the book is to think of the person vs. situation debate in psychology. The question was this: what explains people's behaviors better, their current life situation broadly speaking or their stable persona? The latter we now call trait theory -- because it is about people's stable psychological dispositions -- and won the evidence debate, at least, academically. Things haven't improved much for situationism since then with the downfall of previously popular experiments such as the Stanford prison experiment, and Rosenhan's psych ward study. So instead of thinking just about typical westerners, we can also think of humanity at large. Sometimes people move around (immigrate). Thinking of each ethnic group as a person to be explained, we can thus look at whether the same ethno-person behaves similarly in different situations, say, whether they live in Somalia, Sweden, or USA. Here we must clarify that there are some issues with measurement of many psychological traits. We don't really, in general, have perfect scales so that we can track people's absolute standing on some trait across time and place (we simply don't know how to construct such tests). We can, however, track relative differences. So we can see whether Somalis living in Somalia (taken as a country) perform well economically, and we can check whether Somalis who moved to USA or Sweden perform well economically. In each case we find that they do rather poorly everywhere we find them, again, taken as a group. We can repeat this method for any other set of natio-ethno groups across various countries, to see whether the relative differences remain relatively consistent across situations. Jones provides some examples of this:

He suitably adds a fitting anecdote to this chart:

For the planet as a whole, the Scandinavian countries—Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland—are usually up at the top of the list. In 1997 this fact showed up in a particularly shocking way: a Danish mother visiting New York City went into a restaurant to eat and left the stroller outside—with her baby in the stroller! Someone called the police, naturally. The mother, Anette Sørensen, was arrested and “child welfare authorities briefly took charge of” her fourteen-month-old girl.14 The mother patiently explained to authorities that in Denmark, it is totally normal to leave a baby outside in a stroller while a parent pops into a store. After all, who would steal a baby?

It’s just common sense that you can leave a baby outside while you dine indoors at a restaurant. At least it’s common sense in Denmark, a land with incredibly high levels of trust in strangers.

As a Dane, I will say that I have seen this many times, and no one cares. Americans are paranoid in comparison. Too much true crime TV, perhaps.

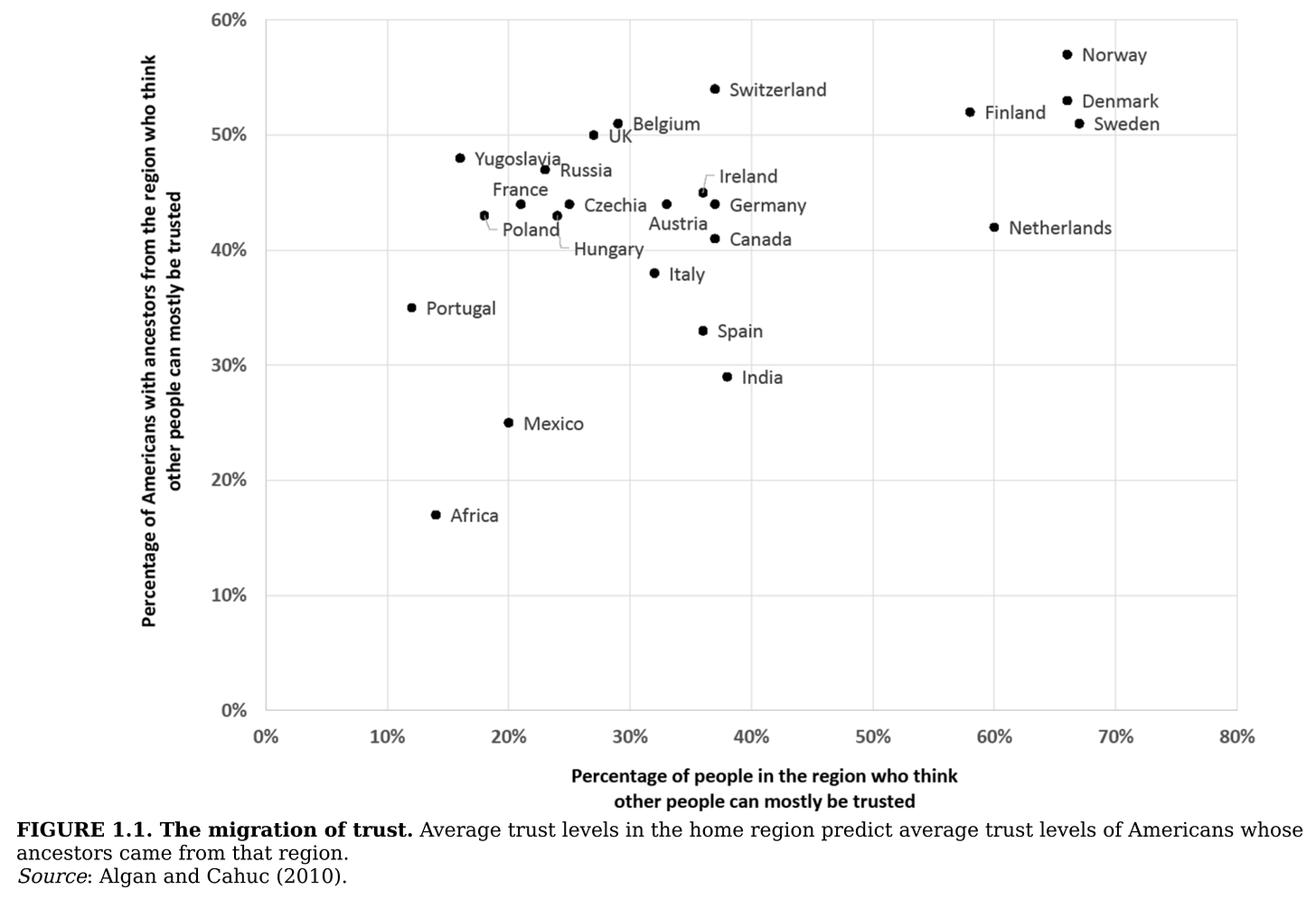

In this case, in some American surveys, people are asked whether they have ancestry from a long list of natio-ethno groups, and one can look up the relative standing of countries on the same question if one can find it. Assuming that people across time and place understand this question the same way (measurement invariance holds), one can then compare them on the same scale. In this case, a relatively decent correlation is found. Since Americans who say they have ancestry from Spain or Norway in the USA are usually descendents of people migrated a long time ago and who have mixed ancestry, these effects are surprisingly, maybe suspiciously, large. By comparing various datasets like the above, one can compute a crude metric of persistence of attitudes across countries:

Let’s start off with the second generation and beyond: adults whose parents, grandparents, or great-grandparents were immigrants. Among that large group, Algan and Cahuc found that current trust attitudes back in the ancestral homeland did a very good job predicting trust attitudes of Americans whose ancestors came from those homelands.15 Forty-six percent of the home-country attitude toward trust survived, when compared against migrants whose ancestors came from other countries. People from high-trust societies pass on about half of their high-trust attitudes to their descendants, and people from low-trust societies pass on about half of their low-trust attitudes. On average, hyphenated-Americans appear to get about half of their attitudes toward trust from the land that comes before the hyphen.

But maybe that 46-percent number comes mostly from second-generation immigrants, those born in America. Maybe if you looked just at the fourth generation, you’d find that the great-grandchildren of immigrants have become indistinguishable from other Americans. Algan and Cahuc check that theory out, looking only at those fourth-generation immigrants, people whose great-great-grandparents were the most recent ancestors to live their full lives overseas. And what did they find? The same 46 percent persistence.

Jones also proposes the Spaghetti model of cultural mixing:

Consider the case of spaghetti. The Order of the Sons of Italy—a group I’d love to join if I could make a halfway credible claim to Italian ancestry—says that about 6 percent of Americans have Italian ancestry.19 Yet National Geographic reports that about 12 percent of all restaurants in the U.S.—one in eight—serve Italian food.20 And everyone knows why so many restaurants serve Italian food: because it’s delicious. It’s not just Italian Americans eating the pizza and pasta and veal chops; it’s pretty much everyone. What started out as a lower-class ethnic cuisine of southern Italians adapted to its new American home—adding more meat, in particular—and became one of the great culinary defaults that’s been embraced across American ethnicities.

So, when it comes to spaghetti, Italians came to America, and Italians changed America, making it just a little bit more like Italy. A naïve statistician who analyzed American dining choices might say, “It looks like Italian Americans and all the other Americans are eating pretty much the same food as each other. They’re all eating burgers and spaghetti and pizza and hot dogs. It looks like the Italians pretty much fully assimilated!”

But of course, that statistician would be missing a big part of the story: the spaghetti and pizza. When it comes to food, Italian Americans and all the other Americans met in the middle—they changed each other. The Italians took some steps toward the other Americans, and the other Americans took some steps toward the Italians. To some degree, the Italians assimilated the rest of us. It’s an obvious point once you think about it, but it’s one that too many students of immigration ignore: You can’t tell whether migrants are assimilating to the preexisting culture just by looking at the post-migration culture.

No doubt true. Immigrants in Denmark are probably more trusting than those who remained at home, and Danes are now less trusting (sensibly so given the crime issues the migrants bring with them), and Denmark changed a bit for the worse.

With regards to the more typical economist focus on money, Jones spends a lot of time talking about the Putterman and Weil study:

Around fifteen years ago, two economists at Rhode Island’s Brown University took up the task of answering this question. David Weil and Louis Putterman ultimately published their findings in 2010 in the Harvard-run Quarterly Journal of Economics. The paper has a great title: “Post-1500 Population Flows and the Long-Run Determinants of Economic Growth and Inequality.”5

By any measure, both scholars are famed economists, and both excel at getting a lot of mileage—a lot of intellectual oomph—out of simple concepts. This paper continues that tradition. They start with a grid—a migration matrix—that keeps track of who has moved where over the last five hundred years. They explain why the question of who moved where is so important for understanding national prosperity: “The further back into the past one looks, the more the economic history of a given place tends to diverge from the economic history of the people who currently live there.”6 Those words hint at a big idea that Putterman and Weil back up with hard evidence: if you want to understand the prosperity of a particular place—a particular country—focusing on the ancient history of the land itself will tell you only so much. A major part of the story, and the more insightful explanation, comes from focusing on the ancestors of the people who now live there.

We all know that from the 1500s through the 1700s, a lot of Western Europeans moved to North and South America, and they violently forced millions of Africans to move as well. In addition, many people left China and moved across Southeast Asia, especially in the 1800s as the Qing dynasty weakened and those who were able tried to jump off that sinking ship. Other migrations happened too: Dutch migrants to southern Africa, many French to Polynesia and to the tiny island of Mauritius off the east African coast, Japanese migrants to Brazil, many Portuguese to Indonesia and to the tiny Chinese island of Macau—the list goes on.

We used their data as a basis of our big Admixture in the Americas study (we are currently working on the 2025 update, stay tuned). Other researchers also built on this line of work ("deep roots") and wrote papers with titles such as The European origins of economic development. So just like one can predict the attitudes of people based on where their ancestors came from, one can also predict the economic functioning of countries from the economic performance of their origin countries. It's not rocket science.

Jones also attacks the usual diversity is our strength, which it can be in a few niche contexts (in a typical heist movie, you need a driver, explosioneer, hacker, love interest, shooter, and big plan guy), but in general it is a liability (imagine a sports team speaking 10 different languages). Jones quotes a lot of reviews from business research on aspects of diversity, most of which are quote negative:

By the 2010s business researchers were finally able to state it clearly: “Research and practice has found the business case for diversity to be elusive.”20 And the team that wrote those words summed up another era of scholarly research into diversity in the workforce—both ethnic and otherwise. Drawing on data from studies run around the world, they reported “no overall relationship between diversity and performance or a very small negative effect.”21

And finally, a team of professors in the Netherlands, in the course of showing that ethnic diversity itself was a predictor of slightly weaker team performance, summed up the way scholars tend to talk about the issue today: “Indeed, it has become a truism that diversity is a double-edged sword.”22

Next up, Jones wants to draw our attention to the power law distribution of global innovation (in absolute units):

PAUL ROMER WON A NOBEL PRIZE for showing how ideas are different from things, how concepts are different from objects. That might sound like an obvious “discovery,” just another example of professors reinventing the wheel, of out-of-touch academics restating common sense in math-heavy jargon.

But notice: I didn’t say Romer showed that ideas are different from things. I said that Romer showed how they were different. And a big part of the difference is that good ideas—like the theory of gravity or the lyrics to the Beatles’ “Hey Jude,”—are cheap to copy, while good things are expensive to copy. Once you have inexpensive printing presses—let alone the internet—people the world over can easily access the world’s best ideas. Great ideas invented in one country eventually get shared worldwide. That means that when it comes to reaping the benefits of new ideas, we’re all in this together: whenever one nation gets better at idea-finding, that’s typically the world’s gain, but whenever one nation gets worse at idea-finding, that’s typically the world’s loss.2

We’ve already seen evidence that a nation’s SAT score and its ethnic and cultural diversity shape the quality of its government, from its level of corruption to attitudes toward government regulation, to its supply of public goods—and good ideas are one of the very greatest of public goods. So, if national innovation depends partly on government quality (as we’ll see, it apparently does), then citizens of every nation have a strong interest in the SAT scores and in the ethnic and cultural diversity in the world’s high-innovation nations.

The University of Colorado’s Wolfgang Keller is exactly right: there are only a small handful of such nations—and as we’ll see, seven of them stand out as particularly innovative, a group I call the I-7. Whether we look at patents, research spending, or the number of scientific publications, the quest to find great new ideas mostly occurs in just a few of the world’s nearly two hundred countries. There are over seven billion humans on the planet—and each of us, every one, relies on lab work that occurs in the I-7. Let’s find out which countries are these Atlases of scientific discovery, sustaining global innovation on their shoulders.

Is he really talking about national IQs SATs? Well, no, and yes:

Let’s also remember that if the extremely ancient past matters, it will matter for the less recent past, not just for today. Putterman and Weil made this point in their original paper. They used an early version of Comin’s tech index and found that if you were trying to predict a nation’s prosperity today, the year 1500 Technological History (T) beat out their ancient State and Agricultural History scores (S and A). They had a simple and likely correct explanation for that finding: the cultural traits that created past S and A scores ultimately shaped T scores in the year 1500: places with centuries of organized states and a long history of settled agriculture were likely, at least by the year 1500, to be using a lot of the world’s best technology. That makes the tech index in 1500 a shorthand for past S, past A, and other past experiences that spurred a region to adopt the world’s best technology.

But it is of course just a way to make the reader think about intelligence without explicitly saying it (in line with The Hive Mind book). Anyway, so if you count patents or anything else really, you will find that a few large and relatively productive countries produce most of everything new in the world. Of course, the country size is doing a lot of work on this way of aggregating things, and specific legal quirks result in misleading rankings (e.g., Japan files 31% of international patents). But since everybody else benefits from the innovations developed in these 7 relatively large, relatively productive countries, the rest of the world has a huge self-interest in keeping the machine working:

The entire world stands to gain when the biggest countries with the best institutions innovate. And we all stand to lose when they don’t. That means the entire world has a stake in the governance, the institutional quality, of the world’s seven most innovative nations:

China

France

Germany

Japan

South Korea

United Kingdom

United States

And since SAT scores, transplanted cultural traits, and some forms of diversity appear to shape a nation’s institutional quality, that means that the entire world has a stake in the SAT scores, transplanted cultural traits, and forms of diversity that exist in these seven high-innovation nations, our world’s I-7. If any of these nations takes even a small hit to the quality of its government, within a decade or two that probably means a big hit to the world’s stock of great new ideas. And there aren’t any heavily populated, well-governed, strong Tech History nations waiting in the wings to take up the slack if an I-7 nation drifts toward mediocrity. Outside of China and the U.S., the world’s high-population nations lack great prospects for South Korean, Japanese, or German levels of innovation. It’s as if we’re ninety minutes into the movie, and the I-7 are the only heroes left standing who can battle the supervillain of scientific sluggishness.

Citizens of every country on earth should be more than just “concerned” about improving governance in these seven nations. Since these seven nations create the vast majority of the world’s innovation, this calls for more than mere concern. Instead, it calls for obsession.

In my 2017 interview (since deleted but there's a copy on archive.org), I made the same point but more specifically. The world in general depends on the right tail inventing, innovating, researching, and building. This is just as true within a country as it is between them. As such, everybody loses when the few clusters in the world that contain the most such right tail people are disrupted. We see this disruption all over the Western world, but especially in the most critical places. Time and money is wasted on diversity (read: anti-meritocratic) hiring, communist-like indoctrination, and the parading of the mentally ill in public spaces (drag shows, pride events). This must come at a cost of progress. Criminal and unproductive foreigners are imported to the most productive places on Earth where they can cause maximum disruption (the capitals of Western Europe, Californian cities). This is crazy and not even in migrants' own long-term interest. However, modern Western politics seems to have forgotten everything about long-term interests (massive COVID debts, short-sighted democratic vote buying). I could go on, but you get the point.

Jones spends a chapter talking about the unique Chinese experience in Asia. This is basically just the thesis of World on Fire by Amy Chua, but from a positive perspective. Not about ethnic conflict, but about how much better off the South Asians with more Chinese neighbors are. The Chinese may own most of their countries, but if their own salaries and standard of living increases by some substantial percentage, we have to ask ourselves how much self-determination is worth. Humanity as a whole may face the same question soon if general artificial superintelligence is created (yes, I know there are skeptics among my readers, I have finally started reading the case for GAI skepticism).

Finally, Jones reviews the evidence for the United States specifically (his home country). Some economists worked out that one can estimate the ancestry composition of each county (3000+ units) by looking at migration patterns. Thus, in this way, one can look at the varying estimates across time for the same units, and see how this affected their relative standing on socioeconomic status indicators. They unsurprisingly found that these help explain between-county variation, and it is a strong method.

What about causation? Obviously, 'culture' that transfers with people even when they lose their native language (and native culture in any normal sense), and also stays present across sometimes 200+ years in a new country, this doesn't sound a lot like culture, but it does sound like genetics. Jones presumably doesn't want trouble, so he says:

How Culture Is Transplanted

Obviously, the story of aspirin is a metaphor for the cultural transplant channels we’ve investigated. We know pretty clearly that culture persists and that culture substantially survives migration, but we really don’t know exactly why it persists. As we head into the middle of the twenty-first century, that’s the state of knowledge on the crucial role that culture plays in national economies: it’s like a lab experiment where we can be relatively confident that correlation really is causation, but we can’t be at all sure where the causation really comes from. We can’t be sure why cultural traits are so persistent. Culture today is a lot like aspirin in 1800.

Are group cultural differences 100 percent genetic? Are they 100 percent teachable and easily changeable, something fixable with some regular public service announcements on Facebook? Or instead, is there a third option, that culture is a set of switchable focal points, social norms that are hard for one person to change alone but fairly easy to change if we all do it at once? In other words, are cultural norms a lot like deciding which side of the street to drive on?

If the focal-point theory turned out to be true, then in principle there might be some way for everyone in a culture to switch to better, more productive cultural norms, just a little like the way that Swedes all switched from driving on the left-hand side of the road to the right-hand side of the road on 1967’s famous H Day. On H day—September 3—at 4:50 p.m., everyone in Sweden stopped their vehicle and had ten minutes to move their cars to the other side of the road. Then, at 5:00 p.m., they all started driving for the first time ever—simultaneously—on the right-hand side. Perhaps some bigger, much more important cultural reforms could work like that—even some of the most important ones. Or perhaps, cultural persistence is created through some synthesis of two or three of these channels: genetic, individual learned norms, and group focal-point norms. Perhaps different channels matter more for different cultural traits.

But all of that is speculative. And those few sentences represent only the beginnings of a wide range of possibilities for future speculation. Indeed, anything I might write about the why of cultural persistence would be purely speculative. This hasn’t been a book with a lot of speculation, and it’s not going to turn into one now: I leave the speculation to future researchers.

I sure wonder if some people had looked into these matters. Jones doesn't talk a lot about genetics as such, but he does spend a silly amount of time on the wrong theory about genetic distances and phenotypic diversity, no doubt because it was proposed by economists (Galor and Ashraf). In general, this book has the same economist-centric bias as the other books. This is a shame because it would greatly benefit from including findings from other fields investigating the same topic of human inequality. Jones' approach of not confronting the key issue of heritability head on is typical of his books. He seems to want to stay within the Overton window, but go pretty close to the edge, so that the reader will draw their own conclusions, and perhaps seek out some of the evidence slightly to the right of the evidence the book covers. This is also similar to Charles Murray's Human Diversity (2020), which didn't cite any of Piffer's or my work (and neither does this book).

Jones is almost certainly a hereditarian and probably a race realist too, but he's a mainstream academic with a lot to lose so I understand why he doesn't address that aspect directly. I think his work is mostly good at making the case that the quality of people matters most, this being of course totally antithetical to modern western immigration policy.

Jones is a hereditarian. You just have to read in between the lines and see that. If you listen closely to podcasts he’s interviewed in, you can hear that he’s subtly a person who believes that people and not the environment matter and that he vouches for high IQ standards in immigration reform etc.