Good science on national IQs

Contra Shae Mclaughlin on national IQs

Shae Mclaughlin (SM) has a new blogpost attacking national IQs. I thought it would be suitable to provide the usual rebuttal since I don’t see any such post yet. She describes herself as “PhD student in bioengineering at Stanford. Former speechwriter and political adviser. I write about science and what happens when science goes out into the world.”. Her CV seems otherwise ok, with some background in genetics. The opening of the post describes her motives, I guess:

There is an effort underway to discredit scientific institutions and universities on the charge that science has become “too political.” The argument goes something like this: science should be value-neutral, concerned only with objective truth. When scientists discredit research because they fear the political implications – say, data showing that intelligence differs between races and nations – they have abandoned the scientific method in favor of ideology.

It is a seductive argument, and a clever one. It allows its proponents to position themselves as defenders of Reason against the corrupting influence of politics. But the argument serves a purpose beyond epistemology. It provides cover for a specific set of claims that have no legitimate scientific basis yet are presented as forbidden truths that the “woke” scientific establishment refuses to acknowledge. If you can convince people that “scientific racism” is an oxymoron – that science deals only in truth, and truth cannot be racist – then you can launder a centuries-old ideology of racial hierarchy through the prestige of science itself.

Fortunately, we have herself to set the record straight. Idealized science is an open field, in the sense that anyone can come in and contribute or criticize (though she has no relevant publications).

Her post contains some typical left-wing history information beginning with Aristotle, eugenics, and how Steve Sailer once had a mailing list. I just glanced over since it’s irrelevant. Getting to the empirical claims meat:

But ideology alone cannot sustain itself indefinitely. It requires the appearance of evidence. Enter Richard Lynn’s “National IQ” dataset, which purports to rank countries by average intelligence. This dataset, first published in 2002 and updated several times (most recently in 2023), is now maintained by David Becker at the Ulster Institute for Social Research and contains 660 studies spanning 130 countries. It is cited by every major proponent of human biodiversity. The dataset is also garbage. Not flawed, but still useful garbage. Not rough, but directionally correct garbage. It is the kind of garbage that, upon close inspection, can only make sense in the shadow of the ideological project standing behind it.

OK, so it’s going to be an attack on the Lynn Becker dataset. Poor Richard Lynn’s motives are always attacked:

My objection to Richard Lynn is that his methods are indefensible, and that his stated purpose was not inquiry but advocacy. That is not a political opinion. It is a methodological one.

It’s curious because Lynn like Jensen was very apolitical. If you read his works, they rarely mention anything about his own particular politics. Here the reader might sensibly assume that the reason SM sees a lot of politics and ideology is because she is herself very much into politics and ideology (”Former speechwriter and political adviser”). First criticism:

Lynn never published any selection criteria or methodology for how he chose which studies to include in his dataset. Meta-analyses are supposed to specify inclusion and exclusion criteria before data collection begins, to prevent the analyst from cherry-picking studies that support their preferred conclusions. In 2010, psychologist Jelte Wicherts and colleagues at the University of Amsterdam conducted their own systematic literature review of IQ studies in sub-Saharan Africa. They discovered that the only consistent feature in Lynn’s selection process was the IQ score itself: the lower the reported IQ, the more likely Lynn was to include the study.

Lynn’s database of papers predates this modern emphasis on inclusion and exclusion criteria, so it’s hard to fault him for this, unless you want to be consistent and fault just about any meta-analysis published before these standards were created. The underlying criticism is true enough. Yes, maybe if one cherry picked studies very carefully, one could bias results in some direction, and maybe Lynn did this and that’s why his African values are so low. This is a concern for any meta-analysis. I don’t think there’s any solid evidence that reporting PRISMA-like criteria relates to the accuracy of the meta-analysis. In any case, Lynn’s results are basically exhaustive in that he tried to include every study he found. Lynn’s dilemma was this: if he includes every study, critics will complain some of them are of low quality. If he excludes some, critics will accuse him of selection bias. Wicherts et al’s old (2010) studies are a nice point to bring up. It was Wicherts et al themselves who were doing the selection bias. You can read the entire set of back and forths with Lynn et al:

Wicherts, J. M., Borsboom, D., & Dolan, C. V. (2010). Why national IQs do not support evolutionary theories of intelligence. Personality and individual differences, 48(2), 91-96.

Lynn, R. (2010). Consistency of race differences in intelligence over millennia: A comment on Wicherts, Borsboom and Dolan. Personality and individual differences, 48(2), 100-101.

Wicherts, J. M., Dolan, C. V., & Van der Maas, H. L. J. (2010a). A systematic literature review of the average IQ of sub-Saharan Africans. Intelligence, 38(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2009.05.002

Lynn, R. (2010). The average IQ of sub-Saharan Africans: Comments on Wicherts, Dolan, and van der Maas. Intelligence, 38(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2009.05.003

Wicherts, J. M., Dolan, C. V., & Van der Maas, H. L. J. (2010b). The dangers of unsystematic selection methods and the representativeness of 46 samples of African test-takers. Intelligence, 38(1), 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2009.11.003

Wicherts, J. M., Dolan, C. V., Carlson, J. S., & Van der Maas, H. L. J. (2010). Raven’s test performance of sub-Saharan Africans: Mean level, psychometric properties, and the Flynn effect. Learning and Individual Differences, 20(3), 135–151.

Lynn, R., & Meisenberg, G. (2010). The average IQ of sub-Saharan Africans assessed by the Progressive Matrices: A reply to Wicherts, Dolan, Carlson & van der Maas. Intelligence, 38(1), 21–29/30–37 author’s rejoinder context.

Wicherts, J. M., Dolan, C. V., Carlson, J. S., & Van der Maas, H. L. J. (2010). Another failure to replicate Lynn’s estimate of the average IQ of sub-Saharan Africans. Learning and Individual Differences, 20(3), 155–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2009.12.002

Rindermann, H. (2013). African cognitive ability: Research, results, divergences and recommendations. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(3), 229-233.

I think that’s all of them. So who won the debate? Well, are now 15 years into the future, and multiple other unrelated research teams have conducted their own meta-analysis including based on newer studies. What do they find? Well, they find that Lynn was right. In fact, one main goal of David Becker’s recalculations of the Lynn database was to assess whether Lynn had biased or had other mistakes in his calculations. You see, to do this meta-analysis, you need to 1) find studies, 2) note their results, 3) convert raw scores to IQ if not done already, 4) adjust for Flynn effects, 5) adjust for representativeness. Lynn had done these but not in a transparent way. After all, he was just one man without much support and his database was built over decades. Contrary to what SM says, Lynn started collecting these data already back in the 1970s or so. His first review was published already in 1978. There was another major update in 1991 as well.

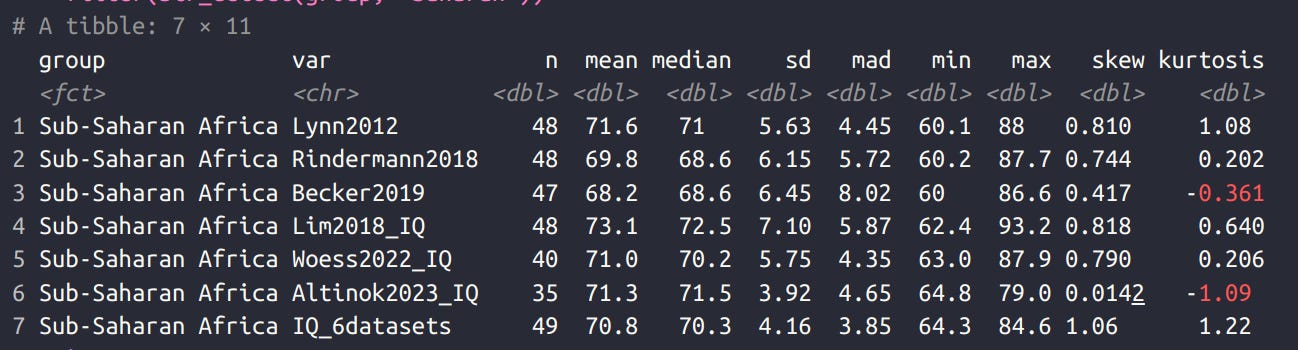

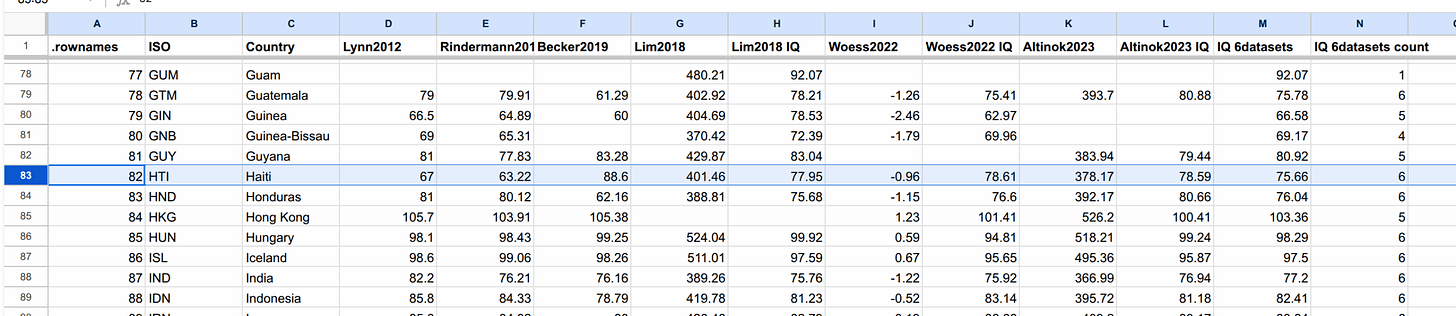

I have calculated the sub-Saharan African mean IQs using the newer meta-analyses 2 years ago. Here’s the results:

Or in graphical format:

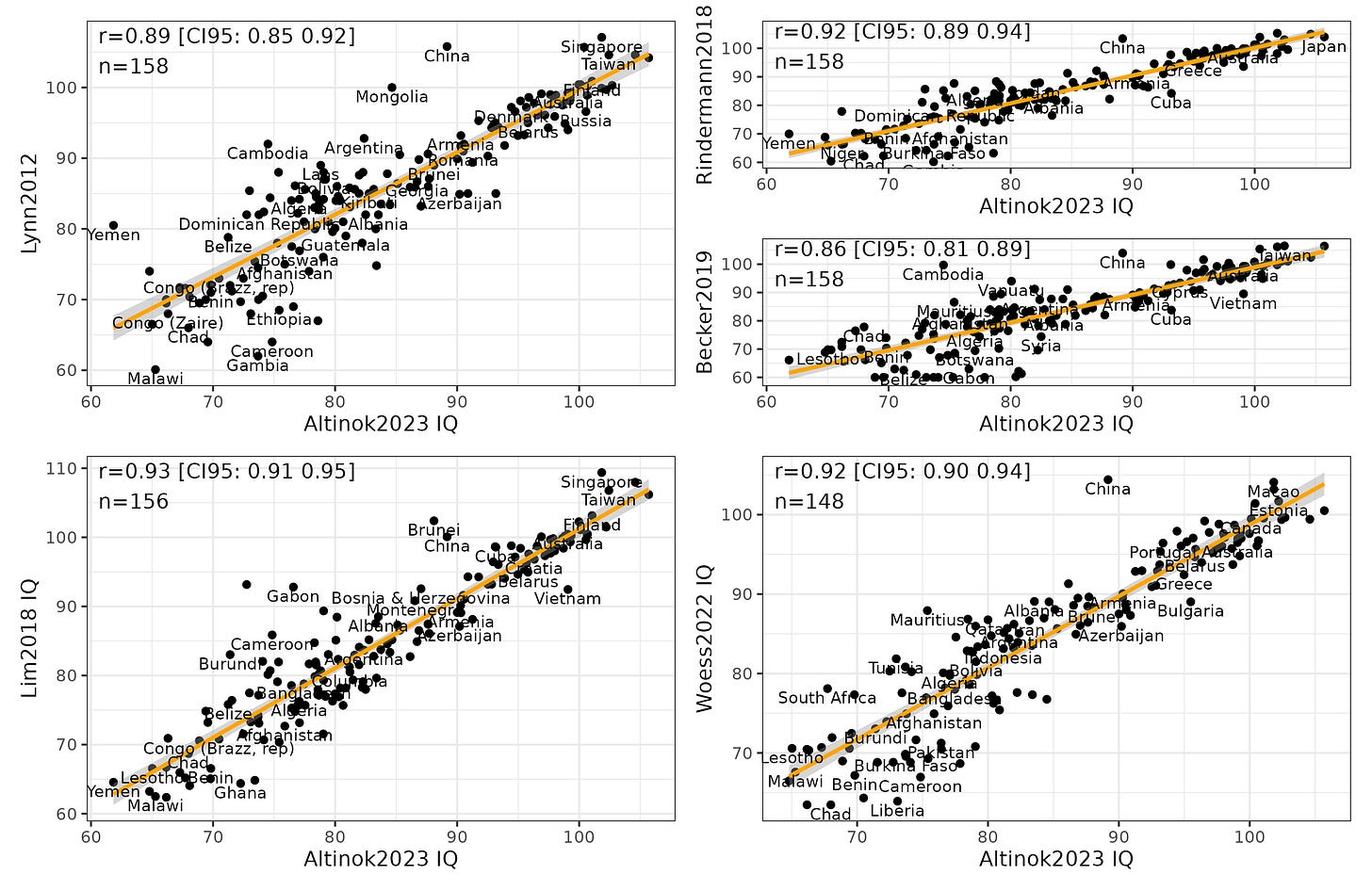

The correlations between the meta-analyses are invariably high. The newer economist studies (Altinok, Woess) in fact don’t use the Raven’s and other traditional psychometric intelligence tests. They rely solely on the scholastic tests carried out mainly on children (PISA, TIMSS, PIRLS, and the various regional tests). But it doesn’t really matter because the results are about the same. This is not surprising because any relatively diverse test of cognitive skills measures mainly general intelligence (g), no matter what the authors call the test. Amusingly, Lynn’s 2012 database actually is the one that provides the (marginally) 2nd highest estimate of sub-Saharan African IQs (72).

The key mistake of Wicherts et al is a common one. They balked at the studies for including many children who were starving or suffering from various kinds of nutritional deficiencies. Often they were taking part in studies run and sponsored by Europeans trying to remedy these. However, the fact of life is that many people in Africa and elsewhere are starving and lacking in various nutrients. If you exclude such samples, then you are not studying poor 3rd worlders as they are, but some subset of upper class 3rd worlders who don’t suffer from these deficiencies.

First, there is the floor effect. The dataset imposes a minimum IQ of 60 – any study producing a lower score gets raised to this threshold. Forty-three studies hit this floor, meaning their actual calculated values were lower still. For Nepal, all eight studies in the dataset registered at exactly 60 after correction. The uncorrected values ranged from 40.7 to 48.3. This is data censorship that disguises the implausibility of the underlying methodology.

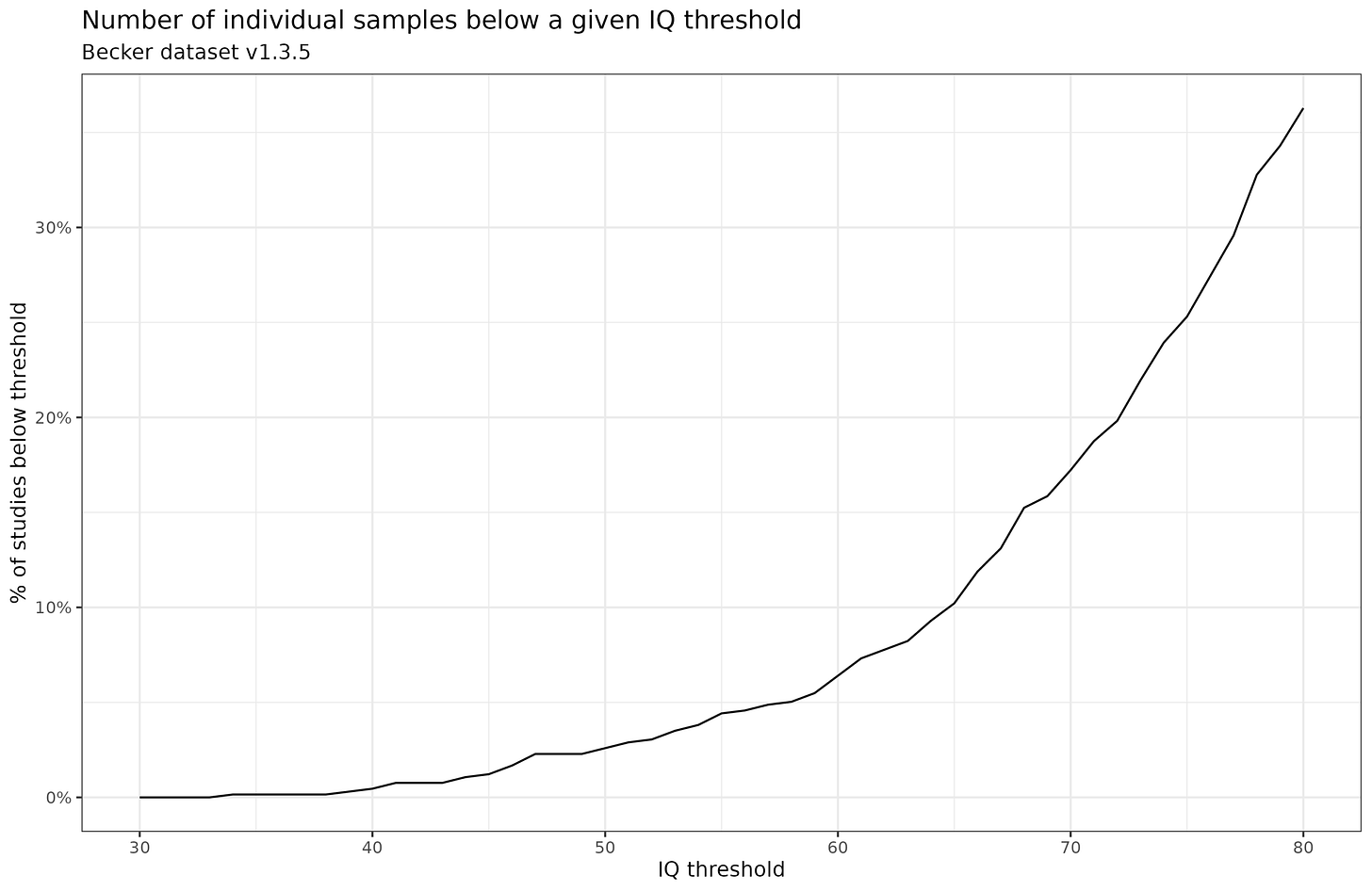

This change was made later in the Becker dataset, not the Lynn 1978-2012 datasets. Why? Well, critics had complained about unreasonably low IQ results for some countries. So Becker decided to impose a floor based on the idea that the results below that were probably due to problems of measurement. Now another critic says imposing a floor is also bad. You can’t win with these people. Speaking of Nepal, I found a large well-done study investigating a nutritional intervention for pregnant women. It produced no effect of the intervention and a mean IQ of 78. Since this is close to that of India and Afghanistan, it’s more sensible than the studies reporting values in the 40s. Other hereditarians have since reported other samples with such low scores, suggesting measurement issues (South Sudanese sample). Subjects may not care about the study, so they don’t try at all, or the instructions weren’t explained properly. Raven’s items requires sustained effort to solve, and if the test is already hard for you, why bother? Who knows what went wrong in a particular study. In any case, if you don’t apply the floor of 60, nothing much changes about the overall pattern. Becker provides comments on the revisions of the dataset and the plausibility of the <60 values on his blog. There’s a setting in his absurdly large spreadsheet that changes the minimum (in the SET sheet). Here’s the % of samples reporting values below a given threshold:

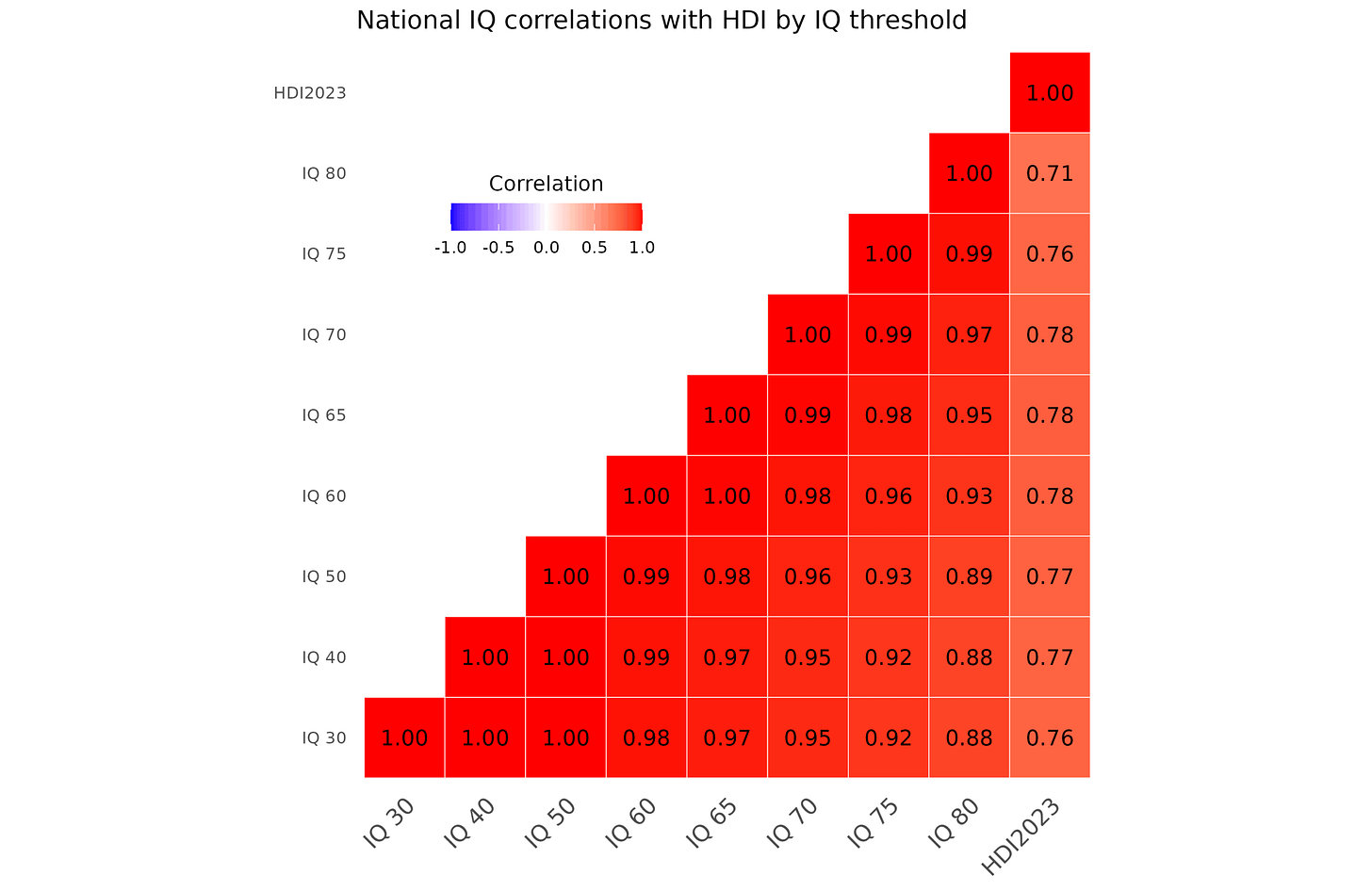

At the value Becker chose, about 6% of samples produced a mean IQ below 60. We can also calculate the country level means (using the quality*sample size as weights for weighted means) using different thresholds and see what difference this makes:

Generally, which low floor (threshold) is chosen makes little difference. The last variable is the human development index from 2023 (latest per OWID). As you can see, no matter which floor is chosen from 30 (none since no samples give <30 IQ) to 80 (Wicherts’ like), the correlation with HDI ranges from 0.71 to 0.78. Empirically, if we use the correlation with HDI as the ground truth, then a floor around 60-70 is optimal (even if the effect is very minor).

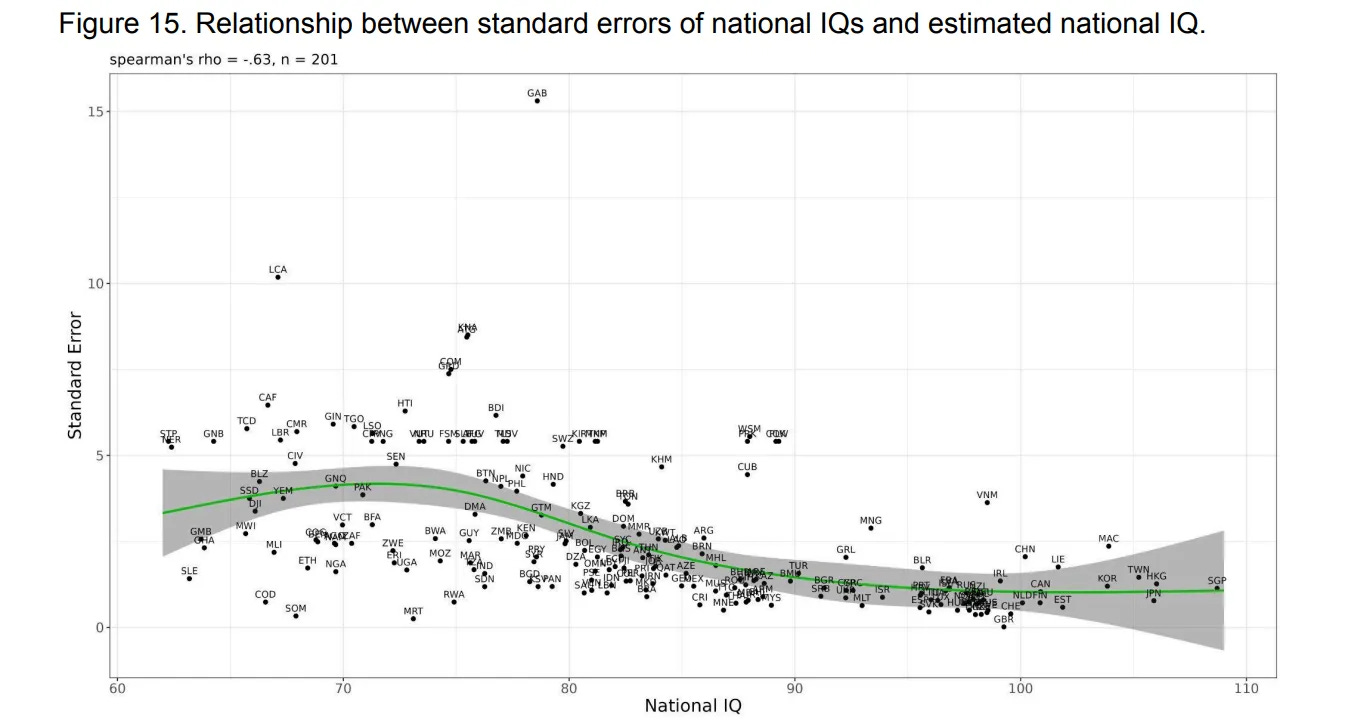

The rest of her post concerns nitpicking low quality data from various countries of American political relevance (e.g. Haiti, Somalia). There’s no point in doing this kind of exercise. Everybody knows that poor countries have low data quality. Inquisitive Bird has a good post on this topic. This is not restricted to intelligence but concerns every datapoint we get from such countries. This is also why researchers are increasingly relying on e.g. satellite data to ascertain the growth of such economies (as well as those from authoritarian regimes that report fake statistics). As such, demanding top quality data is isolated demand for rigor and not generally possible. It doesn’t ultimately matter if Haiti is estimated at 65 or 75 for the worldwide results (it’s a tiny half-island not of much significance). As we can see in the figure above, imposing various different floors make little difference, until we start making the floor so high that real variation is clearly reduced (such as using the floor of 80). Here’s the correlation between data quality (estimated standard error of national IQ) plotted against the countries’ IQ (based on our own work):

We see that generally for countries with IQs below 80 or so, there’s probably a nontrivial amount of error in the estimate of it’s national IQ. You can also discern certain patterns in which countries have more uncertainty. In the top near 100 IQ we have Vietnam, a communist country, and Cuba (CUB) is also above expectations. Haiti (HTI) has significant uncertainty as you might expect. Generally, smaller countries and those beset with incompetent or authoritarian governments have higher uncertainty. This is not very surprising. We can also illustrate this by looking at Haiti’s estimate across different meta-analyses:

Haiti’s estimate ranges from 63 to 89. Ironically, both high and low estimates were produced by Lynn 67 vs. 89 IQ (2012 vs. Becker-led 2019). The economists estimated around 79. The overall average across the datasets is 76 IQ. In other words, no one really knows what the Haitian IQ is, but it’s obviously not near 100.

Recently, I also used Noah Carl’s method of imputing the low IQs using only non-test data. This also depends on the specific methods chosen, but produces estimates around 70 as well.

So the case against national IQs is hopeless:

Cherry picking countries with bad data is a useless exercise because this is expected and normal for such countries, and not unique to national IQs.

Excluding samples of people with various nutritional issues is improper because people in such countries routinely suffer from such problems. Including them is therefore correct insofar as sampling representativeness is concerned.

Various research teams have produced national IQ datasets (under various names) that are very highly correlated and agree well on regional means, including SS Africa.

Meta-regression to impute SS African IQs using non-test variables produce about the same results.

This post’s investigation of artificial floor effects shows that the best floor value to use is around 60-70 IQ, meaning that the true mean IQs are not higher than that and possibly not lower either.

For those interested in more on national IQs, Cremieux has a great review post here.

I admire your patience with these people. Much of the race-IQ debate seems to be babysitting people who cannot reconcile their moralistic biases with obvious scientific truths.

But, in a way, they might be right. If you accept the obvious fact of race differences in socially important traits, a moral hierarchy in practice is likely inevitable. More truth thus means more racism.

Thus, they have to deny reality. The interesting part here is whether they do this consciously or subconsciously.

Has anyone ever studied why they want Africans to be smart so badly?