Good vs. bad scientific questions

Why can't science tell us how to cure hiccups?

The scientific method is a kind of general truth generating approach that involves:

Making some claim (hypothesis) in clear enough language (clarity) ...

... that some observation can be done to figure out if it is true or not (testability).

Having public discussion of such claims and observations (discussion).

Trying to construct causal models based on such claims (mechanisms).

Classifying observations into more and less related kinds (classification).

Science can deviate from these principles. Some scientists used the inputs of others but worked mostly in isolation, at least for a while (little discussion). Similarly, scientists in the private sector work in secrecy at least for a while. Sometimes it is not immediately obvious how to test a particular claim. Some implications of Einstein’s general theory of relativity were only technologically feasible to test many decades later, while others could be tested within a few years. The initial theory of continental drift was difficult to test as humans can’t just wait 100 million years to see if they move, and the theory was largely rejected for some decades.

But what about the role of the questions asked? We could attempt to classify or rank scientific questions as well. Some are better than others. Questions such as whether at the current time you read this, there is an even number of spiders on Earth, could maybe be determined (we could attempt to exterminate all spiders except for some in some labs that we observe), but wouldn’t be very interesting or useful. Interestingness, we can perhaps think of in terms of whether the question’s resolution would have implications for other claims. In Quine’s terminology, whether the claim is strongly connected in the web of belief. Useful would perhaps be a subset of interestingness, concerning whether the resolution of some question would enable some beneficial change in behavior. For instance, knowing whether a small amount of boron helps plants grow is a useful question. If we were to try to make fertile soil on Mars (the soil there is poisonous we think), then we would have to acquire some boron if this is needed or helpful. The answer turns out to be yes to that question. Since we aren’t currently trying to farm on Mars, this scenario is of limited utility, but farmers do test for and manage the boron levels in their soil. Much more important was to learn how the nitrogen life cycle worked, which lead to production of artificial fertilizers, which saved 100s of millions of people from starvation.

If you follow popular scientific discourse you will notice that there are a lot of claims with poor evidence behind them. Sometimes this is for political reasons, but usually it is just because the claim is inherently hard to test. Take parenting advice. There’s a lot of advice with almost no real evidence behind it. The best thing in general we have is that some survey was done asking parents whether they do X (e.g. punish their kids using time-out method), and asking the parents or teachers whether the child behaves well. You might find some correlations, which could mean it works, or could mean other stuff such as genetically shared causes or other family-level non-genetic causes. The correlations aren’t that useful for inferring causality. Ideally, you would somehow enroll some parents in a study, and assign them parenting methods at random, then monitor the kids afterwards over some years. If you check the scientific literature, you will find that such causally informative experiments are exceedingly rare. Humans have been doing parenting for as long as our species has existed. People have been scientifically debating parenting methods since the birth of science. Yet a recent meta-analysis of ‘exclusively positive parenting’ (never punishing) could find only 24 such randomized studies of some kind or another, which includes time-out and other punishments. Given the amount of attention to parenting and the amount of scientific debate (speculation), this is very minuscule amount of good evidence. In comparison, there are probably over 200 such trials on stereotype threat from the last few decades alone (and it turns out most of them show wrong results because of cheating and the phenomena is mostly unreal). Or take a favorite example of mine: hiccups. You can find lots of advice about what to do about hiccups. But there seems to be close to 0 randomized trials about such methods, though there are a few about pharmaceutical interventions (for people who get hiccups frequently). So science can’t really tell us what to do about hiccups despite this being a common annoyance. Why aren’t there studies? Well, imagine you wanted to do such a study. First, there is no obvious financial motive for a company to sell a anything to help you hold your breath, so funding would have to come from the public/state. Second, measurement is hard because hiccups are infrequent and people would have to self-observe at whatever location they are currently in. You would have to ask them to start a timer immediately once they notice they have hiccups, then apply for method they were assigned at random, and then stop the timer immediately after they notice the hiccups have gone. This sounds like a study that could be done, but it just never has been done. I guess no one was interesting enough in this question. By the way, I use the drink water up-side down method, and have used for this 3+ decades with 100% success rate (hiccups stop immediately). As far as I know, there is no proper experiment of this method, but there’s this doctor who said:

In an interview with Business Insider, New York University otolaryngologist (an ENT doctor) Dr. Erich Voigt said that “drinking water upside down” is the only hiccup cure that works, in his professional opinion. But it’s not the water-drinking that does the trick, but the tilting of your head. This movement forces your abdomen muscles to contract, and probably also distracts you from your hiccups as you try to drink without making a mess. Dr. Voigt claims it even helped to cure a patient who had the hiccups for two weeks straight.

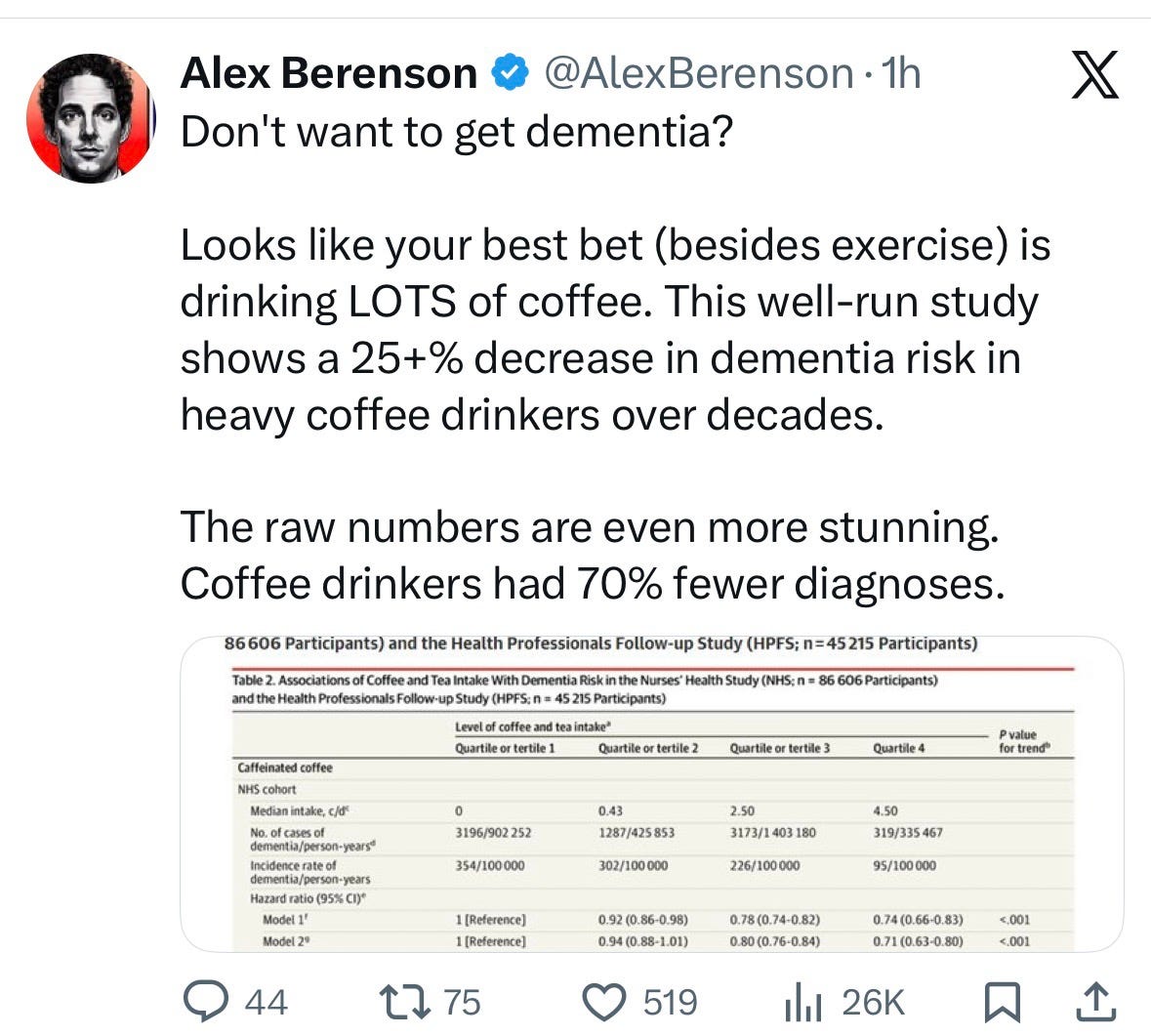

Worse are claims like these:

So does coffee protect against or cause dementia? Well, are you going to randomly assign people to drink coffee for some decades and see what happens? Not really, so you have to rely on observations of natural variation. These kinds of simple observational studies are almost useless in term of causality, since obviously it’s not random who decides to drink a lot of coffee (self-selection bias). I looked up some other studies similar to the one above and they didn’t even point in the same direction (some positive, some negative). Are there better methods? You can find some Mendelian randomization studies but I don’t think this method works in general, so shrug. There’s a large study using a GWAS for coffee consumption and it shows a null or positive relationship to the polygenic scores (more coffee genes, more dementia, p=4%). Basically, I don’t think science can answer this question either. Maybe if we can find some monozygotic twins with different coffee habits. Some twin studies have been done, but seemingly not on dementia and coffee. Well, it turns out there is one such study that is both a monozygotic twin study and a randomized control:

Coffee drinking was compared with tea drinking in monozygotic twins in 18th century

EDITOR,— One of the more peculiar attempts to throw light on the question of whether drinking coffee is bad for one’s health¹ was carried out in the 18th century by King Gustaf III of Sweden. He is better known for instituting the Swedish Academy, the august body of 18 (18 because the king liked the sound of the Swedish word for that number, arton) whom Alfred Nobel later selected to award his prize in literature.

A pair of monozygotic twins had been sentenced to death for murder. Gustaf III commuted their death sentences to life imprisonment on the condition that one twin drank a large bowl of tea three times a day and that the other twin drank coffee. The twin who drank tea died first, aged 83—a remarkable age for the time. Thus the case was settled: coffee was the less dangerous of the two beverages. The king, on the other hand, was murdered at a masked ball in 1792 at the age of 45 and became the subject of an opera by Verdi.

Unfortunately, the sample size is 1 pair.

The point of this post, is that you want to focus your attention on scientific claims or questions that:

Are useful to know (not whether there is an odd or even number of spiders).

Can be known with current data or at least data we can easily gather (not something hypothetically possible in 50 years).

Have implications for other scientific theories.

Finding such research questions is not so easy, which is probably why most science is relatively useless. Of course, most working scientists have other motivations since they must keep publishing to further their career, even if they publish on questions that fail one or more of the above criteria.