National IQ stereotypes are accurate too

Rebecca Sear already trying to suppress the findings

We just published a new article:

Jensen, S., & Kirkegaard, E. (2025). Stereotypes of the Intelligence of Nations. Comparative Sociology, 24(2), 272-295. https://doi.org/10.1163/15691330-bja10134

The authors surveyed a nationally representative sample of 478 Americans on Prolific to assess the stereotypes about national intelligence, and found that these correlated at .78 with measured national IQ s; although the aggregate ratings are accurate, it’s not clear how people determine the average levels of intelligence in a country, whether it’s based on regional stereotypes, economic development, or other methods. Left wingers were slightly less accurate in their ratings of the intelligence of nations (r = −0.21), even after covariates such as age, gender, and race were controlled for. Both race and political views seem to be related to the perception of the intelligence of certain nations; Black people assign much higher ratings to the intelligence of African nations than Whites, and left wingers tend to give lower ratings to the average levels of intelligence of Russians, Israelis, and Americans. Some of the analyses in this article were preregistered.

The background is that prior research has found demographic stereotypes to be very accurate in general. Decades of research has been summarized by Lee Jussim and colleagues a number of times. Typically, if you ask a number of people to rate demographic groups, typically races or sexes, on a number of objectively measured characteristics, the correlation between the average judgment and the true values will be 0.80 or so. For instance, in our study of the sex distribution across occupations in the Netherlands, we found this amazing result:

In another study, we asked Danish subjects to estimate the economic impact of immigrant groups on the state budget (net contribution, that is, revenue from taxes minus expenses), and got this result:

One apparent exception to this finding of high accuracy of demographic stereotypes has been national stereotypes of personality. In one such study:

Consensual stereotypes of some groups are relatively accurate, whereas others are not. Previous work suggesting that national character stereotypes are inaccurate has been criticized on several grounds. In this article we (a) provide arguments for the validity of assessed national mean trait levels as criteria for evaluating stereotype accuracy and (b) report new data on national character in 26 cultures from descriptions (N = 3323) of the typical male or female adolescent, adult, or old person in each. The average ratings were internally consistent and converged with independent stereotypes of the typical culture member, but were weakly related to objective assessments of personality. We argue that this conclusion is consistent with the broader literature on the inaccuracy of national character stereotypes.

The word objective is doing a lot of work here. In reality, the 'objective' measures were self-report personality tests. We know that cross-country survey data has extreme bias (measurements do not have the same meanings), so maybe the stereotypes were right and the personality data results wrong? One study looked into this using actual objective measures of one personality trait, conscientiousness, and the stereotypes of this:

Much research contrasts self-reported personality traits across cultures. We submit that this enterprise is weakened by significant methodological problems (in particular, the reference-group effect) that undermine the validity of national averages of personality scores. In this study, behavioral and demographic predictors of conscientiousness were correlated with different cross-national measures of conscientiousness based on self-reports, peer reports, and perceptions of national character. The predictors correlated strongly with perceptions of national character, but not with self-reports and peer reports. Country-level self- and peer-report measures of conscientiousness failed as markers of between-nation differences in personality.

Their results:

The columns show their objective measures of conscientiousness. One can quibble with their choices, of course, but the difference personality inventory scores (rows 1-3) and stereotypes (row 4, PNC)'s correlations with the objective metrics are striking. Personality inventory data averaged a pathetic correlation of -0.43 in the wrong direction, while stereotypes averaged 0.61. So maybe national stereotypes are not so inaccurate after all. I mean, it is hard to believe they are. I've traveled to 30+ countries and the differences are rather obvious. Just why the personality inventory data are so biased is a very interesting question, I don't know the answer.

Still, their choices of measures for conscientiousness can be questioned, so we decided to try another one: national intelligence. This has the double benefit of both being able to validate national IQ estimates and national stereotypes in a single study. Here's our main result:

We used a fairly representative set of 50 countries of the world. 438 American subjects rated these on a scale from "far below average" to "far above average". We did not ask people using an IQ scale because people don't understand IQ scales, and trying to convert Likert scales into IQ points is a bad idea. The correlation between our best national IQs and the stereotypes was r = 0.78. This value is not different from the other results summarized above. Curious was that the relationship was nonlinear. It appears Americans don't have a good sense of intelligence rankings among countries with IQs below 90 as they were all rated relatively similarly, but Americans do know that the Japanese are smarter than Canadians and Ukrainians. India was a very large positive outlier. This is expected because Americans are familiar with elite Indian immigrants, and many apparently do not realize that these are extremely positively selected. As a result, Americans think Indians are about on par with central Europeans like English and French.

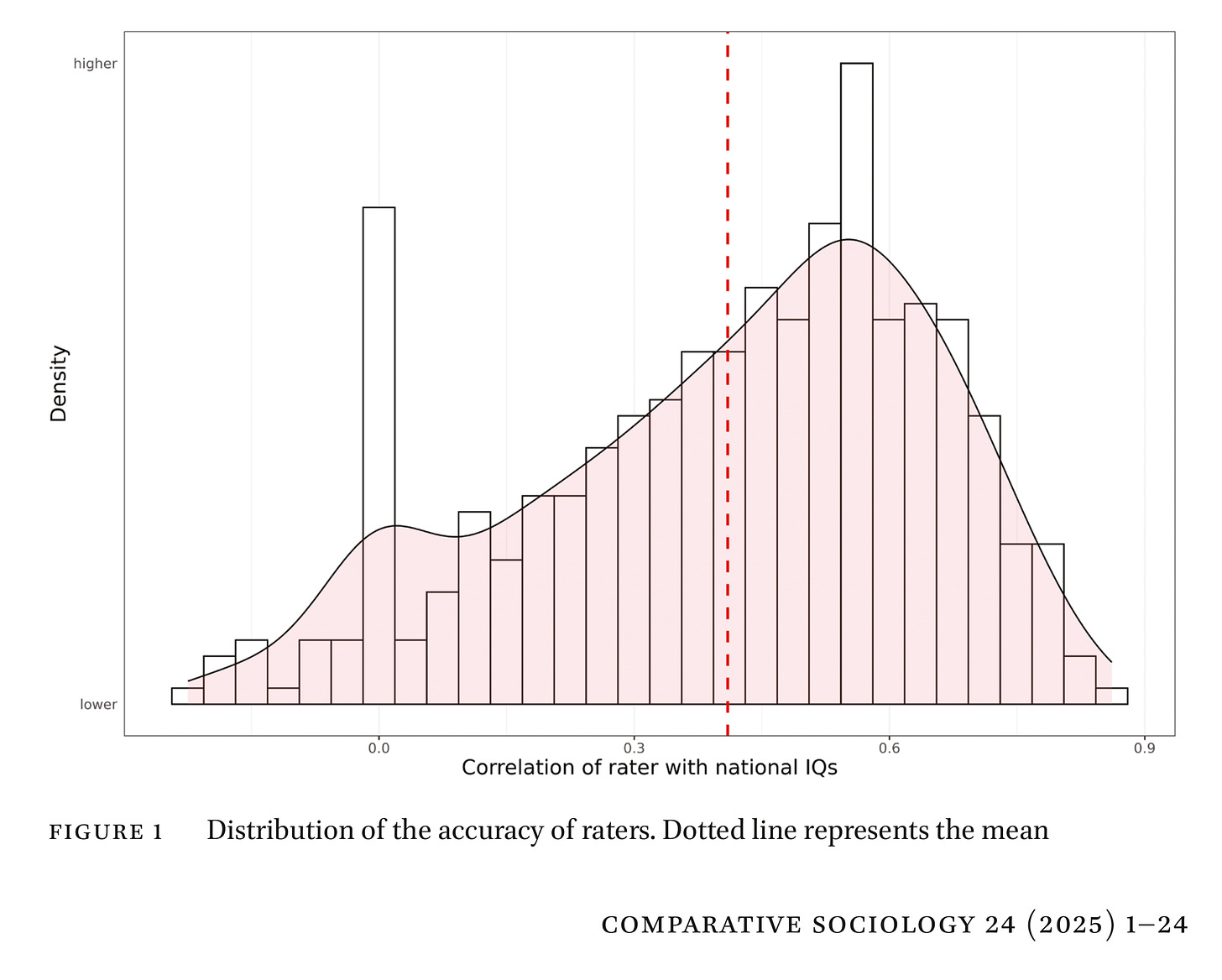

We can also score each person's stereotype accuracy instead of averaging the estimates across subjects. Doing so reveals that there was substantial individual variation in accuracy:

The big spike at 0 is because many subjects rated every country the same, thus making the correlation undefined (0 variance). These correlations were then set to 0 for some analyses. The median accuracy was 0.45, which is not so bad at all considering the usual findings of political and general ignorance among the general population. So what predicts stereotype accuracy?

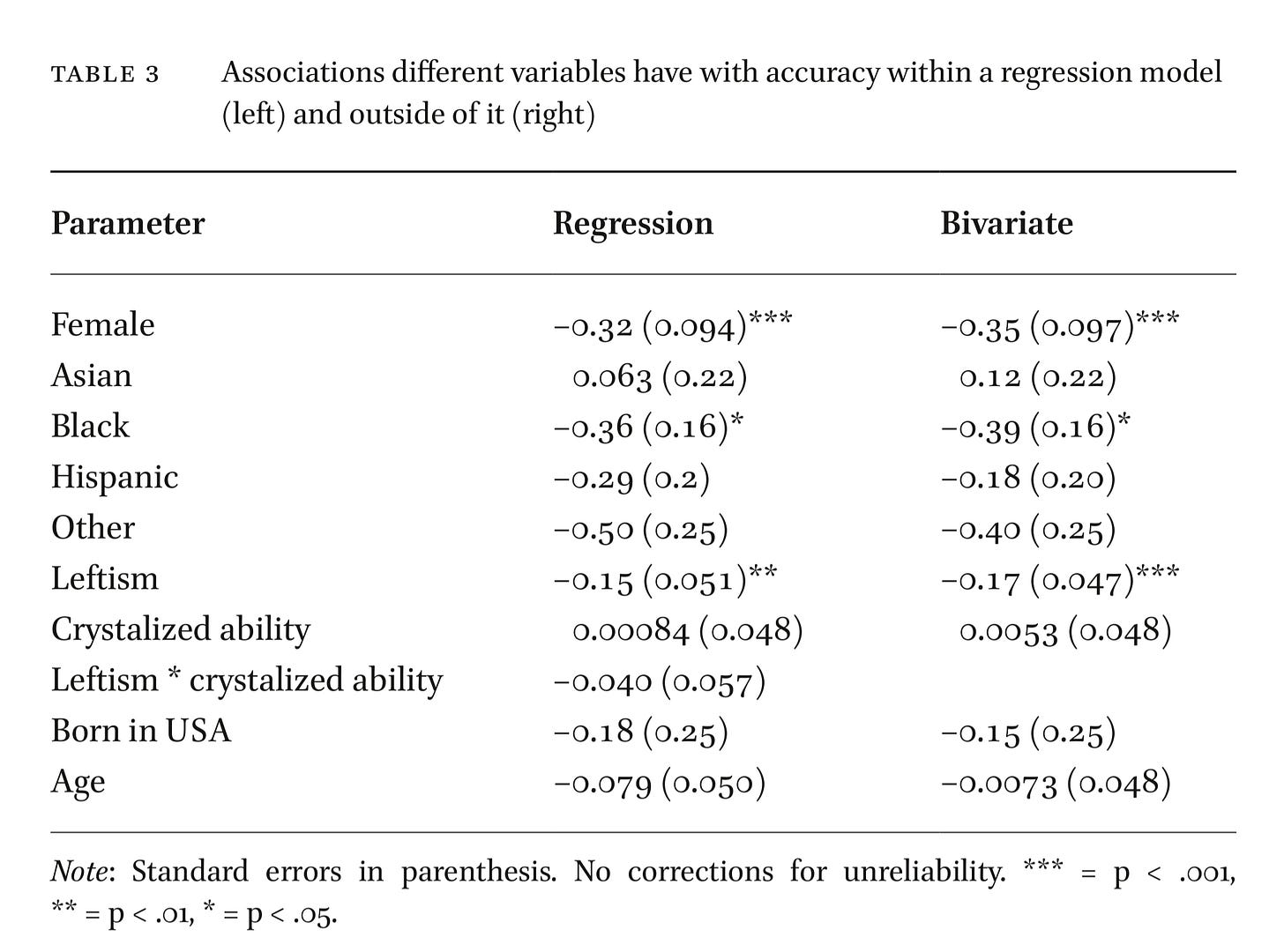

Being female was associated with lower stereotype accuracy (-0.32), which might tell us something important about women and their views on immigration and world inequality in general. The same was true for leftism (beta -0.15). The only strange finding was that crystallized intelligence (30-item test, vocabulary, science, and general knowledge) did not correlate with stereotype accuracy, as it did in every prior study I conducted. We don't know why that is the case. Curiously, the associations were almost the same when used alone in a correlation or when combined in a regression model (compare numbers in the same rows across columns).

Also interesting is to look at which countries are rated higher or lower by groups. Let's begin with leftists:

Leftism correlated with rating poor countries higher, especially African (r = 0.26). This was also true for the communist countries Cuba and Venezuela. Reversely, they also rated United States, Israel, and Russia lower. These 3 countries are associated with right-right geopolitical opinions, as well as the usual American nationalism, which now is a very good measure of rightism. So what about nationalism? We used a 26-item scale of mixed questions, which allowed us to also measure other dimensions of political ideology other than leftism vs. rightism:

American nationalists rated European descent countries higher, and especially America itself and the other Anglos. America first!

Since America has people from all over the world, we can also check whether Africans rate Africans higher in line with positive ethnocentrism:

As expected, African subjects rated African countries quite a bit higher than Whites did. In fact, they rated every country higher than did Whites. This probably reflects some kind of survey bias effect between the races. However, to note, there were only 48 Africans in our sample (11%). The other racial groups were even smaller and their results did not indicate anything too exciting. Asians did estimate Malaysia and South Korea quite a bit higher than Whites did, but not Japan and China. Since most American Asians are from China, the evidence for ethnocentrism was not strong. Asians also rated Saudi Arabia and Romania much higher, but why is that? I have no idea.

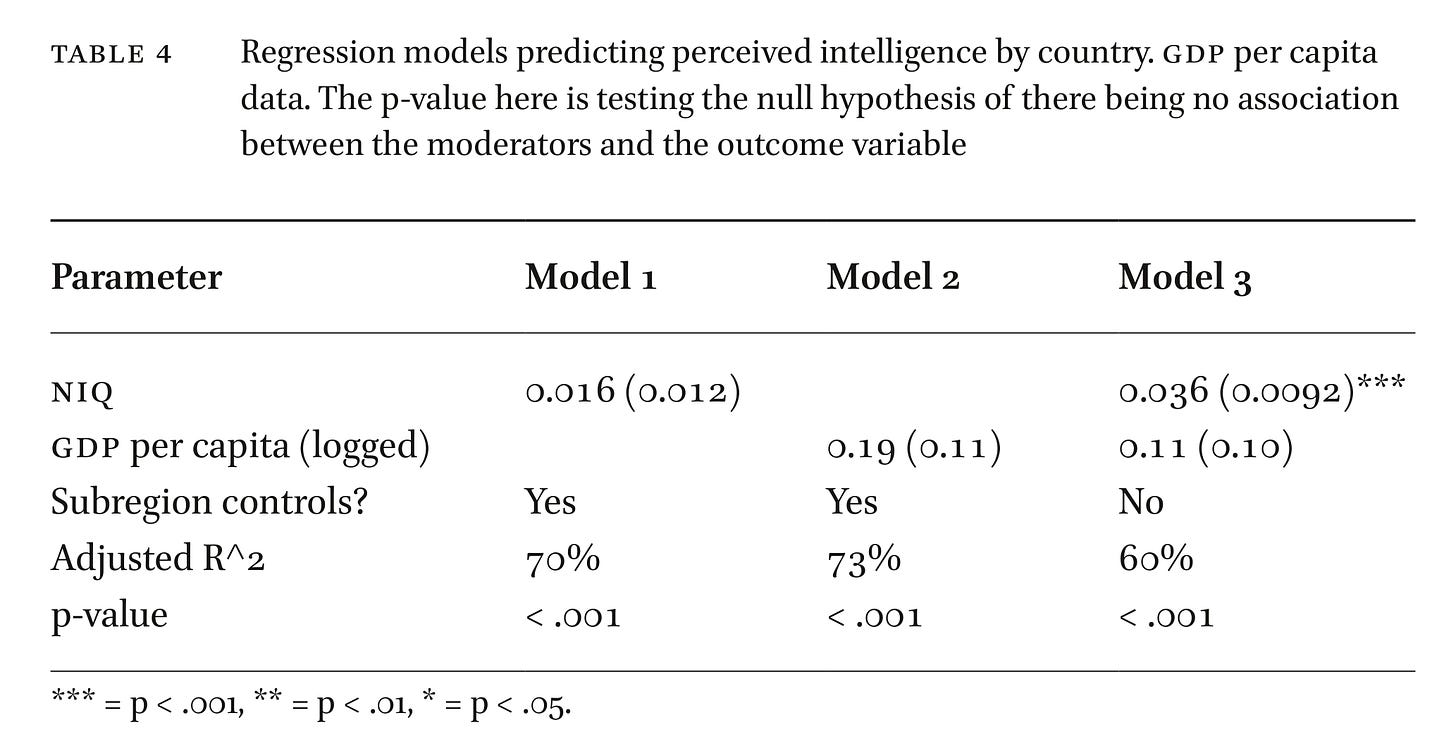

We also tried to figure out if people used wealth (here measured as GDPpc) as a proxy for estimating intelligence. I mean, we cannot expect the typical American to have memorized Lynn's world IQ maps, but maybe they have an idea about the world GDPpc map. We did this using a regression model:

The outcome variable is the perceived intelligence of countries. If we just include the actual national IQ estimates and regional dummies, then national IQs don't predict anything (model 1). Neither does GDPpc if that is used instead (model 2). However, if the regional dummies are removed, actual national IQs predict stereotypes while GDPpc does not (model 3). It doesn't seem that average Americans rely on GDPpc as a proxy. This would generally lead to accurate estimates, but would fail for countries that get their wealth from natural resources, chiefly oil and gas. If you look back at the plot of countries above, you will see that Americans do not think Saudi Arabians are smart even though they are from a wealthy country, and the same is true for the Irish (tax haven).

Overall, then, our study found mostly what we expected. Overall stereotype accuracy was high, r = 0.78 but nonlinear. Being female and leftism predicted worse accuracy, but intelligence did not predict better accuracy.

What is also interesting is the usual stalker censors are already trying to get the study removed from the public view. This is curious because none of the authors have shared the study online yet, and this blogpost was not written! Clearly, they must be spending their time searching for our names on Google or monitoring Google Scholar pages. Censorship fan Rebecca Sear is openly trying to get people to email the journal and its editorial board members:

She also lets us know that she started doing this 2 years ago. Maybe nothing will happen, but maybe something eventually will. These censorship fans previously succeeded in having various Richard Lynn and Phil Rushton papers retracted. It ultimately doesn't matter so much because social media and the internet in general has changed how science findings are spread. You lose, Rebecca!

Interested to discover that Rebecca Sear has failed to update her own webpage to include her trendy blueski ID to go with her Xitter one (or maybe to replace it? she hasn't Xeeted for a couple of months)

Looking at her blueski blatherings she seems to personify the "AWFUL" (affluent, white, female, urban, liberal) stereotype. Censorship is of course a requirement for such people

What was I surprised by when I started reading Lynn and Vanhanen's National IQ work in 2002?

I was surprised Israel is mediocre. I expected France to score a little above the European average. The big gap between India and China was not unanticipated but still strikingly large. Maybe I expected Switzerland to be above average.