New causal variant estimates for intelligence

Well, "new".

There’s a new genetic analysis of intelligence out:

Chen, H., Liao, Y., Tang, L., Wei, X., Li, T., & Chen, W. (2025). Multivariate genome-wide analysis reveals shared genetic architecture and brain structural correlates of human cognitive abilities. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 41596.

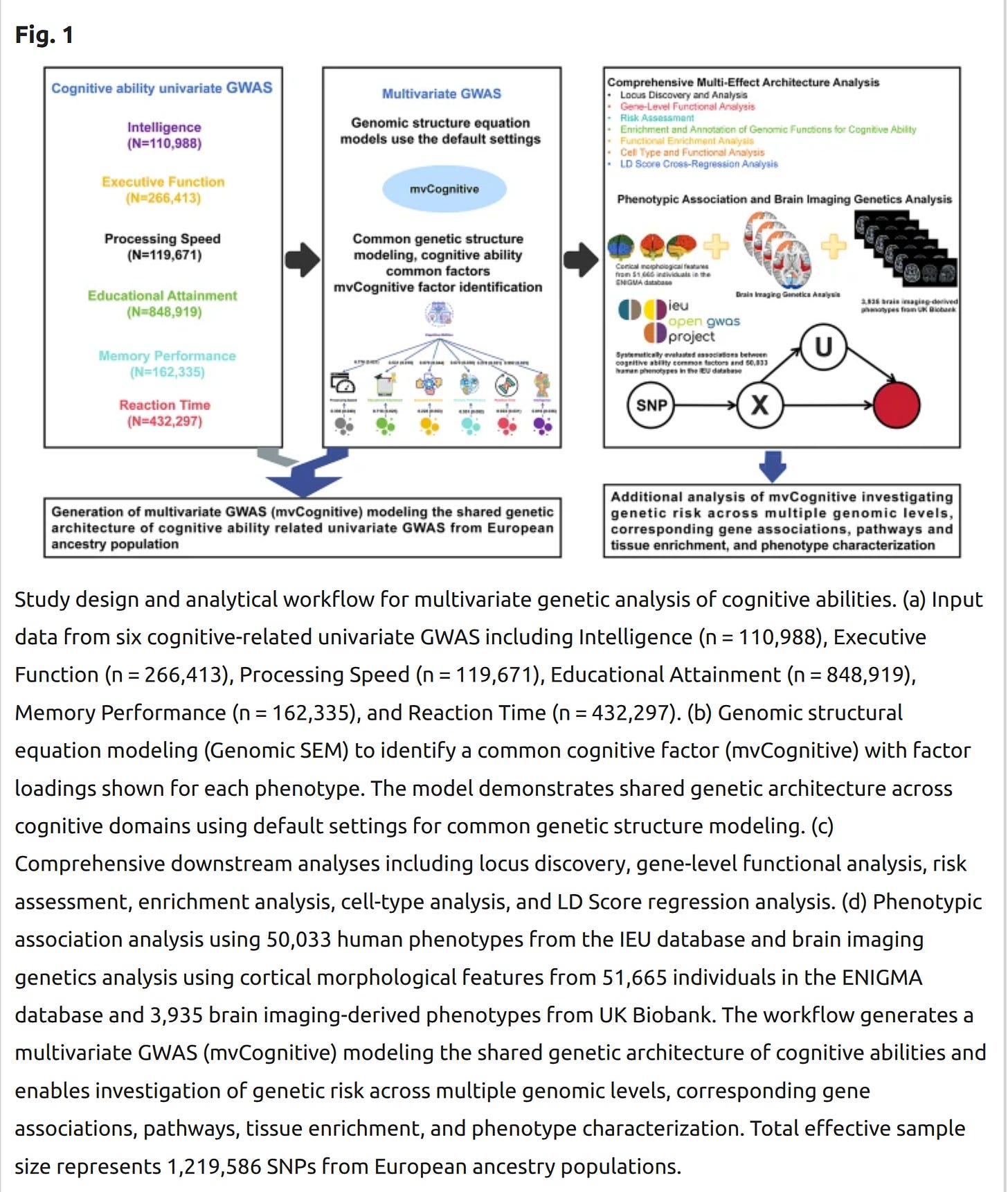

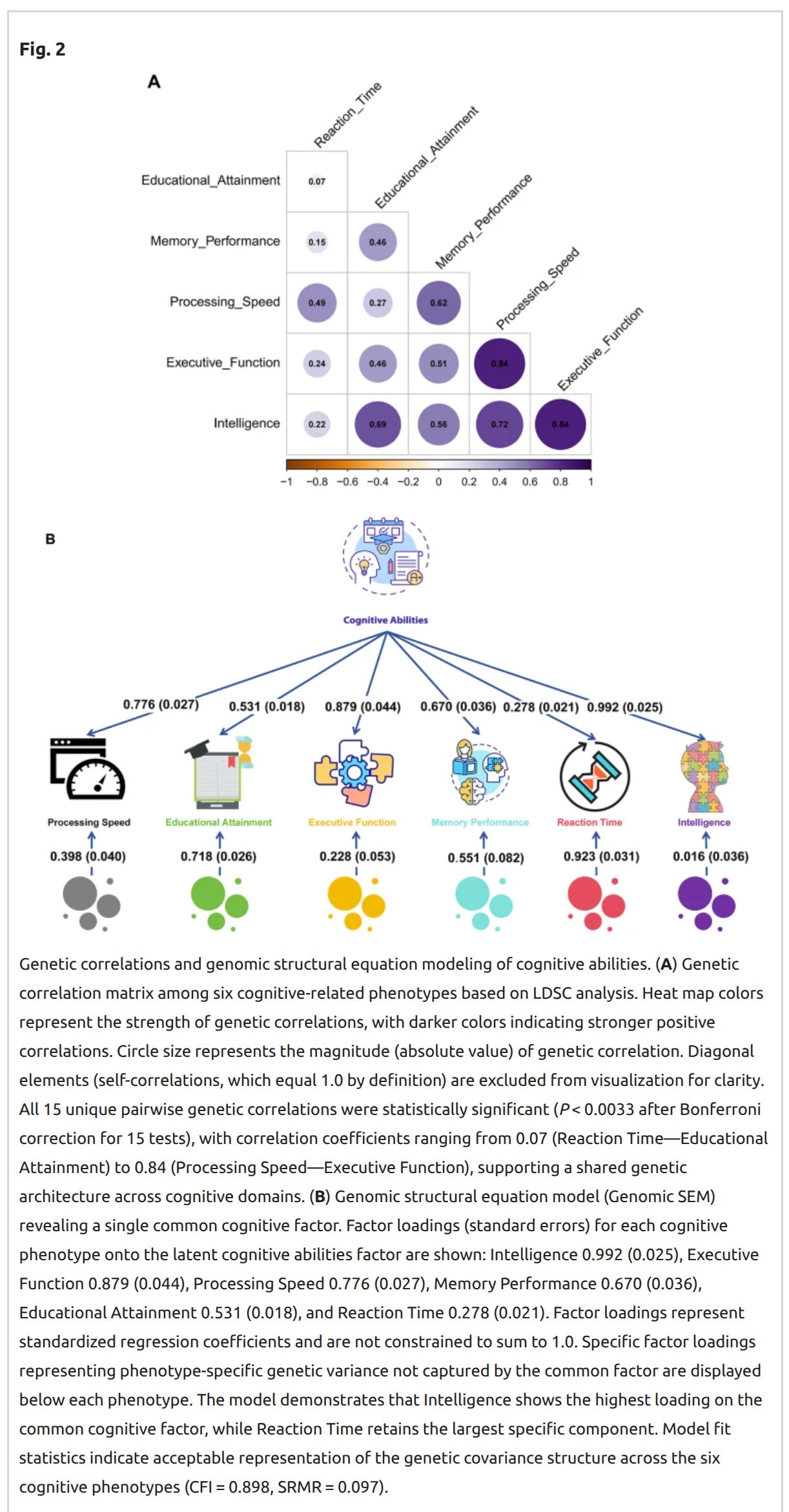

Limited knowledge currently exists regarding the shared genetic architecture influencing human cognitive ability-related traits. We utilized Genomic Structural Equation Modeling (Genomic-SEM) along with multiple post-GWAS methods to estimate potentially causal single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with cognitive ability phenotypic variation. Our study identified 3,842 genome-wide significant loci, including 275 novel loci. Applying multiple transcriptome-wide association methods, we analyzed susceptibility gene signal loci highly correlated with cognitive ability GWAS from tissue, cellular, and genomic element perspectives, identifying 13 high-confidence candidate causal genes and related functional element information. Subsequently, we systematically evaluated 80–90% of currently known human common disease data in the IEU database, along with 3,935 brain imaging-derived phenotypes from UK Biobank and cortical morphological features from 51,665 individuals in the ENIGMA database to determine cognitive ability-related susceptibility factors. We applied the BrainXcan pipeline for brain imaging genetic analysis of cognitive abilities. Additionally, we used summary data-based polygenic scoring methods to systematically analyze the genetic contribution of different chromosomes to cognitive abilities and their risk prediction value. Our study, through multivariate GWAS analysis of cognitive ability common genetic factors, contributes to mapping the shared genetic architecture of human cognitive abilities.

It’s not a new study with more data unfortunately. Rather, it is an attempt at better aggregation and fine-tuning of existing datasets. I often get asked: when do we get more data for intelligence GWAS/genetic models? The answer is that we have more datasets. We here meaning humanity. 23andme published a little known GWAS of their intelligence testing that they added a few years back (one preprint from 2019 about digital symbol substitution test, and a 2020 preprint expanded version with vocabulary etc., n up to 335k). However, as far as I know, the summary statistics are not available for building on, and in their most recent work, they even refused to use their sibling data to estimate heritabilities: “We could not analyse EA and cognitive traits because of ethics restrictions”. It would be nice to know which asshole blocked this research.

Another dataset is the great American Million Veterans Program (MVP). They aim to genotype 1M American veterans, which is awesome. Veterans have a lot of data already measured for them, including electronic health records, military performance, and most importantly, AFQT scores for entry testing. These are scores from the ASVAB tests, which is an excellent intelligence battery. There are some studies using the MVP already. For instance, this 2022 study of height, which used genetic data from 320k people (a cohort description from the same year describes 850k having filled out surveys, this preprint from 2020 describes an initial sample of 485k subjects with genetic data). If the Trump admin. could cut through the red tape here and get GWASs done and published (full summary stats) for all the phenotypes, it would be a great boon to science, and basically free since the data is already collected. In fact, for relatively little money, the NIH should just get cheap 1x whole genome sequencing done on all subjects in all federally funded datasets. The cost per person should be about 50 USD/person including everything. They should target the largest existing datasets with lots of phenotypes already measured. For instance, NHANES series (maybe 200k across all years, some are now dead), or the Nurses’ Health Study (350k total or so).

A third idea is to administer new, better cognitive tests to existing genetic databases. For instance, in the UKBB the existing test coverage is poor (most people have no data) and the tests are very short and produce unreliable data (the fluid reasoning test is 13 items only). There are potentially other large cohorts one could add either genetic testing to, or intelligence testing to so as to obtain both in the same subjects.

A fourth idea is to leverage the Nordic datasets. Denmark has the excellent iPsych, which seems to have about 140k people (1.7% of the population!). They are merged with government data, which includes end of mandatory schooling (9th grade) standardized tests. These have already been analyzed before for genetic findings, but the data are not integrated with other datasets to my knowledge.

Anyway, back to the new study. The relied on the following prior GWASs:

Intelligence GWAS data were obtained from Hu et al. 2025 (GCST90310159, n = 110,988)23. This study was based on UK Biobank fluid intelligence scores (data field 20,016), primarily from individuals of British ancestry, using standardized intelligence assessment tools, providing an important foundation for genetic research on general cognitive ability. This dataset has high phenotypic measurement precision and serves as a core phenotype for cognitive ability research.

Executive Function GWAS data came from Perry et al. 2025 (GCST90503115, n = 266,413)24. This study analyzed multiple executive function GWAS data through genomic structural equation modeling, improving gene discovery efficiency and providing valuable genetic information for higher-order cognitive control and cognitive flexibility. Executive function, as a core component of cognitive abilities, has important clinical and educational significance.

Processing Speed GWAS data were from Carey et al. 2024 (GCST90309368, n = 119,671)25. This study used confirmatory factor analysis (factor 34) to comprehensively evaluate cognitive and processing speed phenotypes, providing an important foundation for genetic research on cognitive processing efficiency. Processing speed, as a fundamental dimension of cognitive ability, reflects the information transmission efficiency of the nervous system.

Educational Attainment GWAS came from Xia et al. 2025 (GCST90566697, n = 848,919)26. This study used multi-trait analysis and genomics (MTAG) methods to analyze educational attainment data, providing strong statistical power for understanding the genetic basis of educational achievement. Educational attainment, as an important external manifestation of cognitive ability, has the largest sample size advantage.

Memory Performance GWAS data were from Hatoum et al. 2022 (GCST90179116, n = 162,335)27. This study evaluated genetic variation in memory function based on prospective memory tasks, providing a foundation for research on genetic mechanisms of memory-related cognitive processes. Memory performance, as an important component of cognitive ability, reflects the capacity for information encoding, storage, and retrieval.

Reaction Time GWAS data came from Hatoum et al. 2022 (GCST90179115, n = 432,297)14. This study provided important statistical power for understanding the genetic basis of cognitive processing speed and neural conduction efficiency based on reaction time measurements. Reaction time, as a fundamental measurement indicator of cognitive ability, reflects the basic functional efficiency of the nervous system.

I don’t know why the names are wrong. The intelligence GWAS is really from Savage et al 2019, not Hu et al 2025 (there is no Hu et al 2025 in their references).

They then integrated these into a systems biology workflow:

The real meat of the paper is that they take up the task that Lee et al 2018 started in trying to find causal variants:

To identify the most likely causal variants associated with our cognitive ability structural equation GWAS, we used SuSIE and FINEMAP, implemented in the echolocatoR R package v.2.0.341,42. We set a probability threshold of 0.95 to define credible sets of potentially causal variants. We used 250 kb windows around each lead SNP to calculate causal inference probabilities for each SNP within these regions. The echolocatoR defines a ‘consensus SNP’ as variants appearing in both SuSIE and FINEMAP results, with average posterior probabilities calculated for these consensus SNPs.

Of course, since they are limited to typical snp-like data, many variants are either not measured or nor imputed well, and if the causal one is one of those in some region, no causal snp can be found in the data. This problem can be solved using WGS data, so we have to wait until further work has been done using the few large WGS datasets (mainly UKBB). Genomic SEM is the same as regular SEM just with genetic variables and appropriate covariances and errors, so one can fit standard models like these:

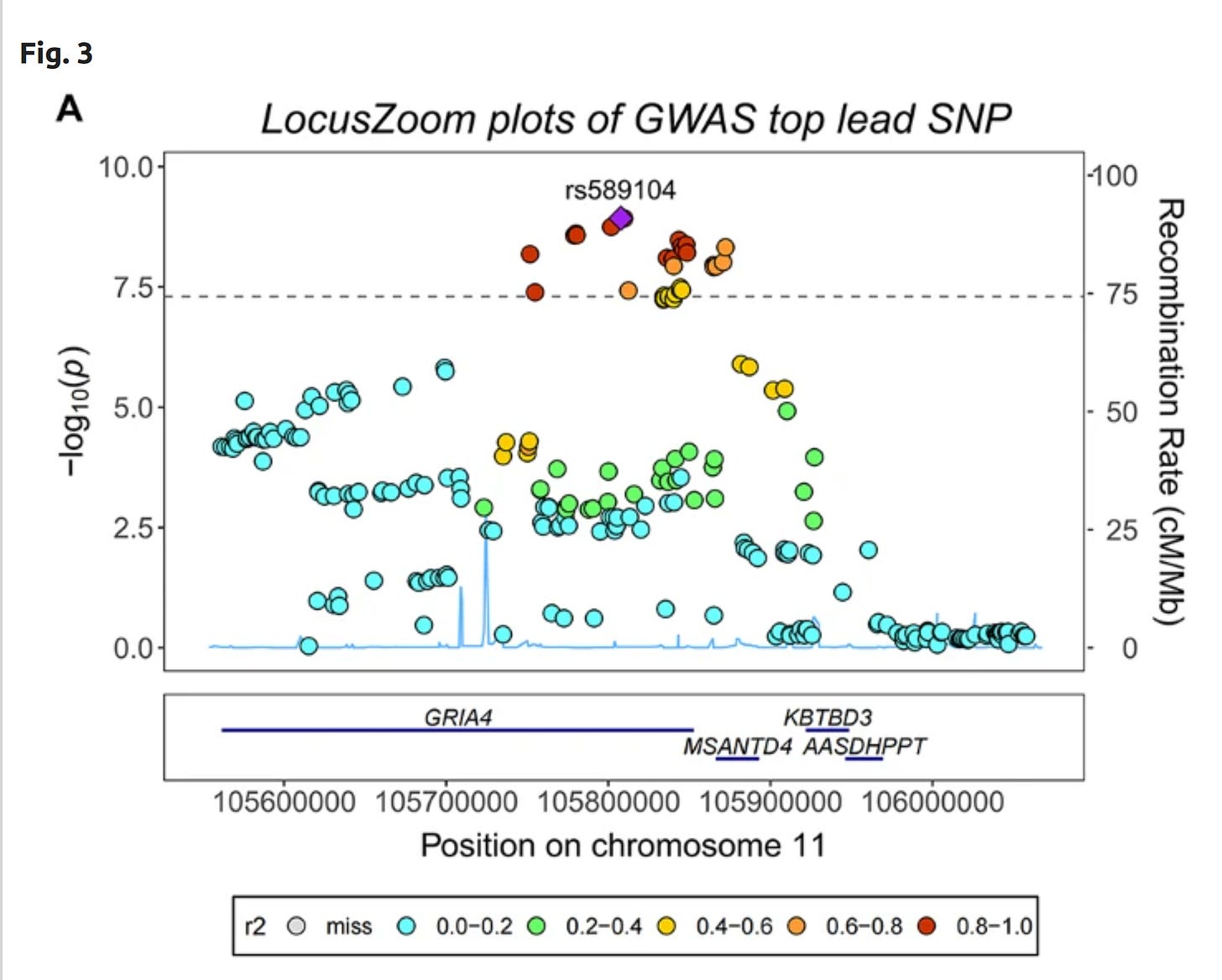

Since one obtains 1000s of snps with p <1e-8 with these datasets, the real trouble is figuring out which snp in a given region is the best one for prediction, or which ones are likely causal. The results look like this:

So in this particular region of chromosome 11, there are many snps with low p values (dashed line = p < 1e-7). These are mostly near the end of gene (protein-coding region) GRIA4 (related to neurotransmission) and the start of MSANTD4. The purple snp is the lead snp, the one with the smallest p value. Colors show the correlation (=linkage disequilibrium) between that and the other snps (in r²).

Overall, their findings showed the regular pattern for these studies:

By extending structural equation modeling (SEM) to incorporate individual variation, we generated a latent factor GWAS that estimated associations between 1,219,586 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and our cognitive ability factor (Supplementary Table 5a). We identified 62 lead SNPs across 1,067 genomic loci at P < 5 × 10–12, and 33 lead SNPs across 322 genomic loci at the more stringent threshold of P < 5 × 10–16 (Supplementary Table 5b,c). The newly identified cognitive ability lead SNPs were primarily enriched in pathways related to neurotransmitter metabolism, neurodevelopment, and synaptic plasticity, while also involving metabolic regulation and immune system modulation.

That is, the areas of the genome that lights up for intelligence-related traits are those that code for pathways related to brain functioning.

While we wait for the summary statistics to be properly posted (the paper has 38 tables attached, all of which are cryptic .txt files), we can note the hereditarian prediction: causal SNPs show larger population differences than non-causal SNPs among those associated with whatever phenotype in study (assuming there is divergent evolution for the particular phenotype). This prediction was previously tested using the Lee et al 2018 causal snp set, but it was underpowered. This new study seems equally underpowered, however, maybe there is something there.

(1) To get the supplemental .txt files to display correctly, open them in e.g. Excel or OpenOffice-Calc, and choose "tab" (and make sure "space" is *not* selected) as the separator (like so: https://ibb.co/p610NZdv); it'll display as a spreadsheet, with everything nicely tabulated therein.

--------------------------

(2) I have sometimes seen people of a certain stripe deny that there is any censorship of genetic data, *in re* heritability (esp. inter-racial) of cognitive traits; have you—meaning our esteemed host, Hr. E.K. (...or, for that matter, anyone else with relevant input!)—written, or encountered, any useful resource(s) on the topic?

(I've encountered many different sources reporting that this sort of censorship absolutely does obtain—we see it here, again: viz., bullshit "ethics restrictions"—but it'd be nice to have a more complete picture.)

Your favourite llm should be able to recreate the tables from the txt files