On genocide and the worst modern ideology

The causes of genocides, and an attempt at ranking major modern ideologies

Some time ago I read Bradley Campbell's The Geometry of Genocide: A Study in Pure Sociology. Like his other books, it's short, to the point, and well worth reading. First, the subject matter:

The most extreme and well-known genocide, the Holocaust, resulted in the deaths of nearly 6 million Jews, about two-thirds of Europe’s Jewish population. Other victims of genocide include 1 million Armenians in Turkey in 1915 and 1916; 800,000 Tutsis in Rwanda in 1994; 400,000 Africans in Sudan between 2002 and 2010; 200,000 Muslims in Bosnia in the early 1990s; 200,000 Gypsies in Nazi-controlled Europe between 1939 and 1945; 200,000 Chinese in Nanjing in 1937 and 1938; 100,000 Hutus in Burundi in 1972; 50,000 Kurds in Iraq in 1988, 20,000 Aborigines in Australia during the nineteenth century; 20,000 Hereros in South-West Africa (now Namibia) between 1904 and 1907; 10,000 Haitians in the Dominican Republic in 1937; thousands of California Indians in the 1850s; and 2,000 Muslims in Gujarat, India in early 2002.

All of these are cases of genocide, or, as I define it here, one-sided, ethnically based mass killing. Since genocide is one-sided rather than reciprocal, warfare is not genocide.1 Since it involves killing on the basis of ethnicity, killings on the basis of class or political identity are not genocides.2 And since genocide is mass killing, the suppression of a language or religion, the forcible transfer of children, and the non-lethal deportation of ethnic groups are not genocide.3 This definition is narrower than some, broader than others.4 It captures what most people mean by genocide, though, and it is easy to apply to actual cases.5

The goal of the book is to explain genocides, that is, under which conditions they happen. The cruelty seen in these situations is hard to read about. Some examples:

A U.S. Army officer describes a group of women who had survived one of the marches: “In addition to their clothes being dirty, worn out, ill fitting, tattered and torn they were covered for the most part with human stool which was spread for the most part all over the floor.… They were too weak to walk to evacuate their bowels” (quoted in Goldhagen 1996:331). During their march these women were so hungry they tried to eat grass and, at one point, a rotting pile of animal fodder. Yet their guards even prevented them from eating food offered to them by German civilians. They beat prisoners who tried to accept food, and one guard took the food and fed it to chickens (Goldhagen 1996:347–48).

If we look closely at the killing in other genocides, what we see is similar. In 1994 Rwanda we see Hutus kill their Tutsi victims with low-tech weapons such as machetes and clubs studded with nails. They chop off arms, legs, and breasts. They throw children down wells (Diamond 2005:316). They impale people like kebabs (Hatzfeld 2005a:81). They cut the Achilles tendons of those they cannot kill right away to keep them from running (Alvarez 2001:109; Taylor 2002:164). Japanese soldiers in 1937 Nanjing bury their Chinese victims up to their necks and then run over their heads with tanks. Others they nail to wooden boards or set on fire (Chang 1997:87). They rape young girls before slashing them in half with a sword. They rape a Chinese woman and then kill her by lighting a firecracker they have shoved into her vagina (Chang 1997:91, 94–95). In 1860s California four white men kill every member of a group of thirty Yahi Indians, including infants and small children. One of the killers switches from a rifle to a revolver during the massacre because, as he puts it, the rifle “tore them up so bad” (quoted in Kroeber 1961:85). In 1915 Turkey, Turkish gendarmes play the so-called game of swords, which involves tossing Armenian women from horses and impaling them on swords sticking up from the ground (Balakian 2003:315). In 2002 India we see mutilated and charred bodies in the aftermath of Hindu attacks on Muslims: “None of the bodies were covered. They were all burnt and shrunken. There were a few bodies of women where ‘lola dandas’ [iron rods] were shoved up their vagina” (quoted in Ghassem-Fachandi 2006:135).

Since by definition, genocides are systematic killings of ethnic groups, these result from group conflicts. He goes on:

The fundamental cause of genocide is overdiversity. Whenever two previously separated ethnic groups come into contact, conflict results. And wherever two ethnic groups live alongside one another, conflict is present. The latter situation may not seem to involve an increase in cultural diversity, and at the societal level it may not. But in any multicultural society people are constantly encountering those who are different, increasing the diversity in their lives. Diversity is thus an unstable property of social life, and as Black puts it, “who says diversity says conflict” (2011:102). This applies to all types of diversity, including political, religious, and ethnic diversity. All lead to cultural clashes.

Genocide does not always happen in contexts with ethnic diversity, there is usually some kind of triggering cause, a change in status:

An increase in ethnic diversity alone may lead to genocide or similar behavior, such as when certain tribal groups kill all outsiders they encounter (Black 2011:103). Usually, though, something else must happen: an inferior group rises (or threatens to rise) or a superior group falls (or is in danger of falling). These social changes are understratification, reductions in stratification. Genocide normally involves superior ethnic groups attacking inferior ones, but prior to the genocide, the stratification between these groups decreases, and this causes the conflict that leads to genocide. Note that even though this involves a change in inequality rather than culture, all conflicts that occur across cultural boundaries—such as across ethnic boundaries—are in danger of becoming cultural conflicts. When murders or thefts cross ethnic boundaries, they are no longer just murders or thefts of individuals, but offenses by one group against another. Even if the original conflict has nothing to do with ethnicity, interethnic conflict has the potential to become collective, with each side mobilizing its own ethnic supporters.10

He gives the full example of the Rwandan genocide:

Many other cases of genocidal conflict, though, do not begin with sudden increases in diversity. In Rwanda Tutsis and Hutus had lived alongside one another for centuries prior to the 1994 genocide. The degree of overdiversity was low, the result of fluctuations of cultural diversity in daily life rather than the drastic increases that arise when previously separated groups come into contact. The degree of understratification, on the other hand, was much greater. The minority Tutsis had been politically subordinate to Hutus for decades when in 1990 the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF)—consisting mostly of Tutsi exiles from Rwanda—launched an invasion from Uganda. Prior to this, Rwanda’s ruling party had faced an internal political challenge, and the president, Juvénal Habyarimana, had allowed rival political parties to form. After the invasion he began peace talks with the RPF and eventually agreed to what were known as the Arusha Accords, a power sharing agreement very favorable to the RPF.

The Arusha Accords would have excluded a major anti-Tutsi political party from the government, and they would have mandated that 50 percent of Rwanda’s army officers and 40 percent of its troops come from the RPF. The president’s party, though, and later President Habyarimana himself, opposed the agreement and sought to block its implementation. Others too began to see the RPF invasion and the Arusha Accords as a threat to the gains Hutus had made in the 1959 revolution, when the previously subordinate but majority Hutu population had gained political power. Each of the opposition parties split into two factions: a Hutu Power faction, which aligned with the regime to oppose the Arusha Accords, and a moderate faction, which continued to support the power-sharing agreement. The anti-Arusha Hutu Power forces gained further support with the October 21, 1993, assassination of the Hutu president of neighboring Burundi by Tutsi army officers and the anti-Hutu massacres that followed (Fujii 2009; Mamdani 2001; Prunier 1995).

So there are 2 groups in a country, and one is more numerous than the other, but the minority has social power. This creates animosity. At some point, the majority gains that political power, so some animosity is reduced in the majority group. But an outside invasion from members of the same minority group upsets the status quo, and a genocide starts as a solution to the Tutsi problem.

In the Nazi case of genocide of the Jews, there was an initial change in power following the loss of World War 1. A scapegoat was needed. Propaganda and magical and religious thinking along with certain statistical regularities made the Jews a convenient target:

In other genocides the major accusations are completely false, perhaps delusional. This was the case during the Holocaust, where, according to political scientist Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, the Nazis’ “proneness to wild, ‘magical thinking’ … and their incapacity for ‘reality testing’ generally distinguishes them from the perpetrators of other mass slaughters” (1996:412). One false accusation was of Jewish treachery—a “stab in the back” that led to Germany’s defeat in World War I (Friedländer 1997:73–74; Staub 1989:100). But the idea of Jews as organized conspirators went much further. For example, the Nazis believed that all their apparent enemies were simply Jewish puppets. The Nazis’ form of socialism—National Socialism—differed from both capitalism and communism, and they believed that international Jewry was the real source behind both of those competing economic systems. This belief was later confirmed, they thought, by the alliance of capitalist and communist nations—the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union—against Germany (Snyder 2010:217). More broadly, the Nazis believed that the Jews sought to dominate all of humanity and that they were thus behind all sorts of other evils. Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels, speaking of the Jews in 1937, put it like this: “Look, there is the world’s enemy, the destroyer of civilizations, the parasite among the peoples, the son of Chaos, the incarnation of evil, the ferment of decomposition, the demon who brings about the degeneration of mankind” (quoted in Cohn 1969:204).

The Jews as an ethnic group had not much to do with the loss of Germany and its allies in WW1 (it seems Jews were over-represented in the army in fact). However, due to Jewish prominence in promoting major ideologies belonging to the enemies (liberalism and communism), as well as over-representation in journalism and social status in general ("In 1914, Jews were well-represented among the wealthy, including 23.7 percent of the 800 richest individuals in Prussia, and eight percent of the university students."), made it a convenient fiction that they were responsible for German loss. Most Jews at the time were poor peasants living in Slavic countries to the east who had nothing much at all to do with left-wing Jews in USA and Germany. And even those in Germany itself constituted a meager 500k out of a population of 65M, so thus about 0.7% of the population in 1933. Nazi anti-Jewish thinking was thus not really rooted in rational group warfare, but was mainly mythological. The same points are true for the Armenian genocide after Ottoman losses. In summary form, the model is this:

If one reads World on Fire by Amy Chua and From Third World to First: Singapore and the Asian Economic Boom by Lee Kuan Yew, one gets the impression that some leaders understood this. They witnessed many genocides of the Chinese in Asia, the horrors of communism, and they sought to reduce the factors above. In the case of Malaysia, it expelled Singapore as a country, since it was largely composed of Chinese and this caused racial tensions. After this, Singapore was still left with sizable minorities of non-Chinese. The leaders then sought to reduce ethnic tensions by forcing closer relations between the ethnic groups. Specifically, they were forced to share housing roughly proportional to their population fractions. This reduced cultural distance and resulted in some ethnic mixing. Immigration was controlled to as to keep the ethnic balance roughly as it was, again, to avoid tensions from changes to this.

In Thailand, Chinese culture was diminished by banning the use of their language in schools. The Chinese were converted to cultural Thais. Harsh? Yes, but Thailand experienced no Chinese genocides unlike other countries in the region. Why not? Amy Chua gives some history of Chinese suppression and forced integration in Thailand:

Prior to the 1930s, most Thai Chinese spoke Chinese, attended Chinese schools, studied Chinese history, and maintained Chinese customs. In the 1930s the Thai government declared that Chinese schools were “alien” in character. Their very purpose was “to preserve the foreign culture of a minority population, to perpetuate the Chinese language and Chinese nationalism.” Accordingly, the government passed a decree requiring that in a 28-hour school week, 21 hours were to be devoted to studies in the Thai language. Mathematics, science, geography, and history were all to be taught in the Thai language. In addition, teachers in Chinese schools were required to pass difficult examinations in the Thai language.

As intended, the effect was a severe restriction of the Chinese language. As time went on, the government began closing Chinese schools altogether; twenty-five private Chinese schools were closed in July 1939, followed by seven more a month later. In addition, Chinese books were banned and Chinese newspapers shut down. Chinese social organizations were prohibited, and regulations were passed requiring “Thai dress and deportment.” Chinese culture generally was suppressed in a calculated effort to destroy ethnic Chinese consciousness and identity. At the same time, more subtle pressures for assimilation played a role as well. As late as the 1960s and 1970s, any Chinese with ambitions to succeed had to pursue a Thai education, adopt a Thai surname, speak the Thai language, and, ideally, marry into a Thai family.5

The Chinese Thai were thus erased as an ethnic group, but not via genocide as defined above (I am aware that the UN and others have expansionist definitions). They were not killed, but forced to assimilate culturally thus eventually genetically.

Trade and thus interdependence is another way to prevent genocide:

We see something similar with European settlers and American Indians.14 Where interdependence was greatest, genocide was absent. For instance, in the seventeenth century, the French—who established settlements to enable fur trading with the Indians—had more peaceful relations with Indians than the English did. In the French settlements, those who were not trying to trade furs were there to evangelize among the Indians, and both of these tasks required cooperation (Nash 2000 [1974]:44; see also Senechal de la Roche 1996:117). In the early eighteenth century, however, when the French established permanent settlements along the lower Mississippi, trade with the nearby Natchez was minimal, and conflicts became violent. Eventually the French killed at least one thousand Natchez and sold four hundred of them into slavery. Others fled to find refuge among other tribes, and the Natchez ceased to exist as a sovereign people (Nash 2000 [1974]:47–48).

From this perspective, one sees that global trade, and strong integration of markets in e.g. the European free trade zone (that eventually became the EU) has probably decreased the chances of war and thus genocides. Even the Nazis were reluctant to kill highly integrated German Jews:

Many German Jews were highly assimilated—culturally similar to and intimate and interdependent with German Christians. Why did this not protect them against genocide? The answer is that sometimes it did. For example, the Nazis initially exempted intermarried German Jews and their children from the Final Solution. Even though Nazi propaganda condemned all Jews and especially condemned intermarriage and miscegenation, they behaved more leniently toward German Jews who were socially close to other Germans. Later, on February 27, 1943, in what was meant to be the final roundup of Jews from Berlin, they began arresting intermarried Jews and Jews working in armaments factories. They separated the intermarried Jews (mostly men married to non-Jewish women) and held them at a welfare office. The intent was to deport them to the East, but after a massive protest from their wives and others, the men were released, and almost all of them survived the war (Stoltzfus 1996:xxii, 209–57).

Moreover, despite some assimilation, more culturally distant Jews were highly visible. Prior to the Holocaust, Eastern European Jews had immigrated in large numbers to the cities of Germany and Austria. In 1852, for instance, only 11,840 Jews lived in Berlin, compared to 108,044 in 1890 (Rubenstein 1983:146; see also Brustein 2003:104–7). And if Germans were distant from immigrants from the East, they were even more distant from those Jews who remained in the East—the first and most numerous of the genocide’s targets. The mass killing of Jews began in Eastern Europe, along with the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union. And most of those killed were Eastern European Jews, who made up the vast majority of European Jews. For example, three million Polish Jews were killed—half of all of those who died in the Holocaust—compared to only 165,000 German Jews.

This case reveals somewhat of a paradox. The Nazis blamed the Jews for the loss of WW1, but the local Jews, who presumably had the largest influence, were the ones who were spared the most, in proportional terms, unlike the east European Jews, who had little to do with the WW1 loss, but who were killed the most. From a rational perspective, it makes little sense. This brings us to the degree of genocide:

Separation prevents ethnic conflicts for obvious reasons. But even genocides have degrees of intensity along key dimensions. The Holocaust was particularly gruesome, being almost entirely one-sided, extreme in proportion (about half of European Jews died) and extreme in scale (~6 million). Even the Nazis first tried to increase the distance by way of deportation:

Expulsion was not an option prior to the Holocaust either, at least not after previous plans fell through. In 1939 and 1940 the Nazis had planned to forcibly resettle the Jews under German control (Browning 1992:6; Gellately 2003:248; Valentino 2004:170–76). One idea was to deport them to the outskirts of the German empire—the Lublin region of Poland. When this proved impractical, they considered deporting Jews to the African island of Madagascar. Their inability to quickly defeat Great Britain, however, made this impossible, and they largely abandoned the idea by September 1940 (Browning 1992:19; Valentino 2004:172). War with the Soviet Union further reduced possibilities for resettlement, and in 1941 Nazi policies increasingly involved mass killings of Jews (Aly 2000:73–75; Browning 2004:187–188; Pohl 2000:86–90; Weitz 2003:129). Clearly any of the Nazis’ schemes of mass deportation would have involved some genocide, but the degree of genocide reached unprecedented levels as separation became more difficult.

This also reveals a conflict between their two goals: eastward expansion lead to more Jews in their lands. When deportations became impractical, genocide was the only remaining ideological option.

Finally, as for the common participant in genocides, there needs to be some motivation aside from ethnic hatred. The main motivations were theft of property and land, sexual (rape), and workforce (slavery). These factors are common in most human warfare historically, where typically soldiers were given the right to loot when cities were taken. All of these motivations were also present in WW2 in the case of the Nazis.

Morality and genocide

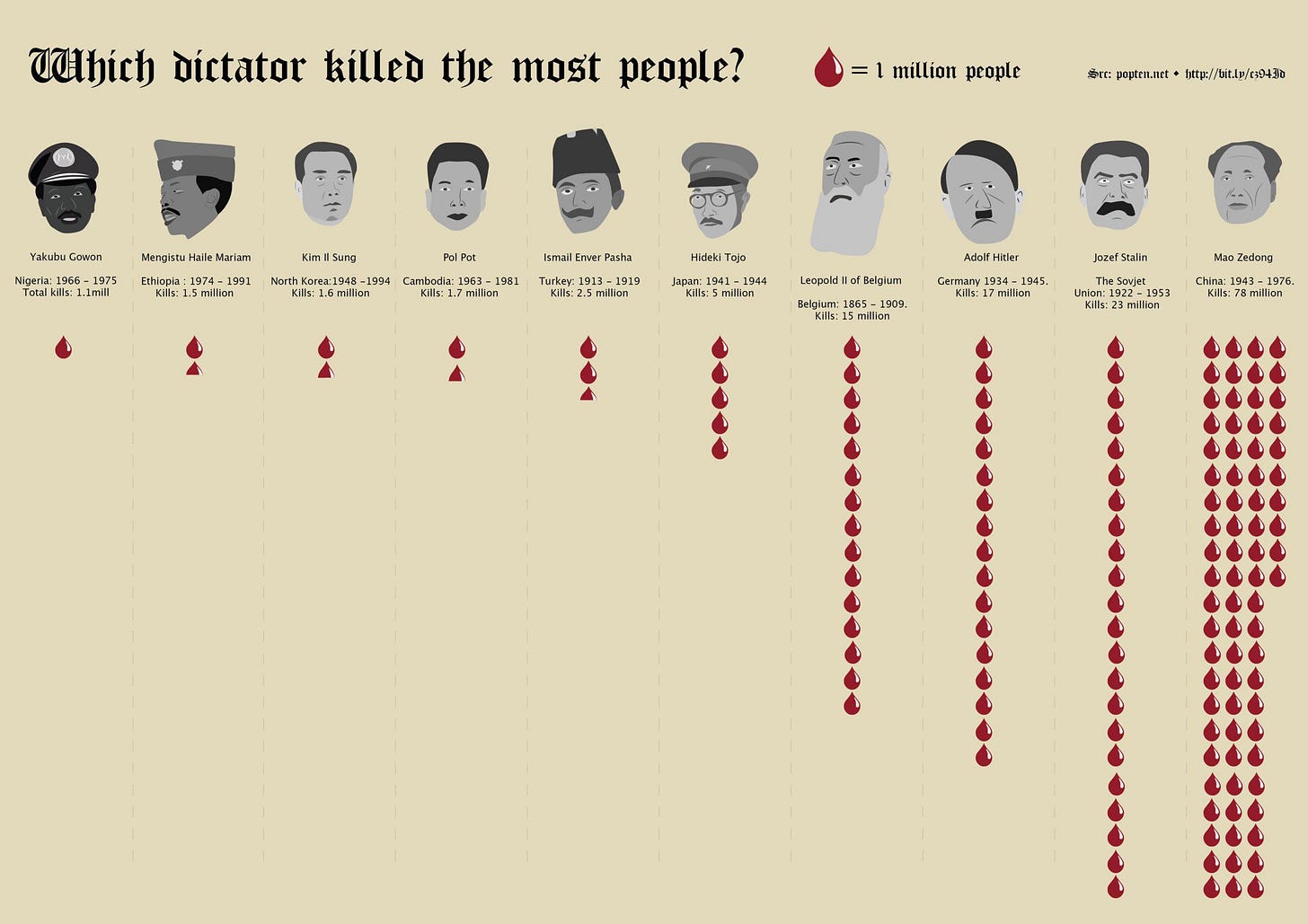

Genocides are extremely evil by modern standards, even if they were common by historical standards (e.g. in the old testament). But if we are to rank ideologies on a scale of evilness, genocide-proneness is not the only factor. Many mass killings of people are not genocides because they are not ethnically targeted. The typical cases of communist cruelty are not genocides. Mao's China killed mainly ethnic Chinese, and mostly due to political incompetence (starvation due to failed policies), not from direct violence. Pol Pot's Cambodia likewise targeted their own ethnic group, not foreigners. Communism does not generally kill through genocide. The largest exception, to my knowledge, is the Ukrainian genocide by Stalin (Holodomor), which did mainly target Ukrainians. If you are a utilitarian, you may not care whether killings were intentional or not, but most people agree that evil intentions are very important for moral judgments, and our legal systems agree (the punishment for accidental killings is sometimes zero, whereas for intentional killings is usually severe). From this perspective, most communism caused deaths were unintentional (exception: Pol Pot's were largely intentional), unlike the deaths caused by Nazi ideology (warfare and genocide). From this perspective, then, using just this popular figure to judge dictators is insufficient:

I can't vouch for the numbers, as it is a free floating figure from the internet, but it looks roughly correct.

There are two further complications to this. First, from a Steven Pinker perspective, proportions matter. Not listed above are people like Ghengis Khan. He and his sons caused immense suffering in their day. Wikipedia has a death toll list (of course, Wikipedia has a left-wing bias, and this may skew some counts on the list), which gives the number of deaths as 20-60 million. But this happened in the years 1207–1405 where the world population was much much smaller than when Mao's policies resulted in a similar number of dead. In some sense, then, Ghengis Khan's killings were much worse if we adjust for population size of the world. It is a murky question from a utilitarian perspective of whether such an adjustment is needed or not. If one is interested in the decline of violence from a statistical perspective, it is surely necessary. If one is interested in morality, a case could be made that a death is a death. However, I think that we can agree that if there was a world population of 100 Pandas, then killing all 100 of them would be much worse than if there was a world population of 1000 Pandas, and killing 100 of them. One is a 100% loss of the population, the other is a mere 10%. Extermination is very bad.

Second, from a human capital utilitarianism perspective, deaths are not equal. If one wants to take into account the future well-being of humans (and animals) on the planet, clearly, some humans are more important than others. Some humans produce many more suffering reducing innovations than others, and some are more prone to causing suffering than others. Cambodians do not contribute much of anything to global human civilization, so in a cold-hearted utilitarian sense, it is better they died than someone else. From this perspective, the deaths that Stalin, Mao, and especially Hitler caused were worse than average given the contributions of the peoples they killed. I recognize that anti-Semites will point to the problems Jews have caused from promoting terrible ideologies, but Jews are also extremely over-represented in science and technology. I think the latter outweighs the former.

Given all of the above, I find it difficult to say which modern ideology is the worst. A good case for communism (left-wing extremism) can be made in that it is an ideology that always results in at best poverty and political suppression (East Germany) and at worst catastrophe (Pol Pot and Mao's mass killings, famine). Unfortunately, humans seem to be particularly prone to liking this ideology. No matter how many times communism fails, it remains popular with intellectuals. The Soviet Union and its east Europe puppets, Maoist China, Pol Pot's Cambodia, Venezuela, Cuba, Vietnam, Yugoslavia, Somalia, the list goes on. But most communist states do not result in extreme death counts, and when they do, it is mostly from stupidity, not outright cruelty.

A good case could also be made for expansionist ethnic supremacy like the Nazis, the Mongols, and Ottomans. These regimes generally result in severe death counts and extreme deliberate cruelty (e.g. the Mongol siege of Baghdad in 1258). Hitler's Germany was particularly bad as Germans are a capable people. They were ruthless in their genocide campaigns, and their targets were high in human capital. The aftermath of their loss caused a massive taboo, which still has a large effect on Western culture, and indeed, is a key component in its decline, even among the enemies of Hitler (Anglo-sphere). The moral reckoning following Nazi atrocities causes so much revulsion that westerners seem hellbent on avoiding anything remotely associated with it, even to their own ruin.

I think a good case can be made for generic conservative extremism is less bad than both of the above. Hitler and Mussolini were very bad cases, but Franco, Salazar, Pinochet, various Latin American dictators, kings and so on, were not as bad as communism. Most of these did not engage in genocides or aggressive warfare that caused mass deaths. They did in general suppress their own populations, but allowed markets to work their magic, or in Pinochet's case, deliberately promoted markets with massive success. This is not an apology for such regimes, they are not my favorite, but they seem a lesser evil compared to the other two options above.

What this has missed is the openly genocidal potential in the various Jihadist movements within Islam. Already the death tolls they have elicited far exceed their formal military power and social-economic-technological achievements. They are the new-old look genocidaires operating in coalitions of fanatical believers but adept at linking up with modern western social justice-victimhood narratives. They are currently focussed on the all-purpose scapegoat of aggressive malcontents, tyrants and sadists, namely the Jews. After that they will come for the soft targets in the West. They are and will continue to have Western supporters who may (or may not) like religion but will certainly be attracted to bullying and sadism.

As a non-European and non-Jew, I think of the Ashkenazi Jewish as simply a version of Northern Europeans if they had continued a bit more in the path towards greater intelligence and pro-sociality (at least, the kind of pro-sociality that leads to solidarity with social justice movements; it's not "scheming" either given that Jewish people intermarry at a very high rate). Just as with Northern Europeans, I view this tendency as naive, but quite literally the opposite of evil.

I believe that there are two main kinds of negative racial stereotypes (I don't have evidence for this so Emil could very well prove me wrong; in fact, he probably has already touched on this making this comment redundant lol): those made by people of "lower" social status about "higher" status people, and those made by people of "higher" social status about "lower" status people. The latter are usually unfortunately often true: People complain about crime, lack of pro-social values, lower intelligence, etc. I think that people have less motivation to lie/deceive themselves in that case (I don't think the pull from having someone to look down on is as strong as jealousy). On the contrary, the former often arises from jealousy. It is perfectly self-serving: you can insult/attack them and feel self-righteous about it.

Every time I see Anti-Semitic, Anti-Chinese, Anti-White comments I just imagine the poster with the word "seething" stamped on his head. I won't even debate with such commenters because I see them for what they are.

A relevant article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stereotype_content_model?oldformat=true