People did not used to marry early in the good old times

The European marriage pattern AKA Hajnal line

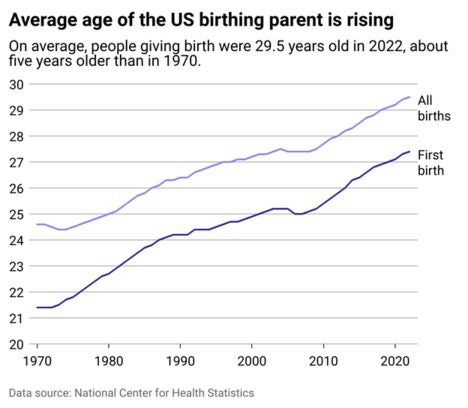

If you look at a plot of age of first marriage and age of first birth (usually following marriage), you might get the idea that the 1960s cultural revolution, feminism or general leftism have caused a historically unique delay in childbearing:

However, this is not actually true. Despite what you might have heard about marrying at 20 or whatever in Victorian England, this was not the norm. The misperception may result from people consuming media relating to upper class or nobility/royal marriages, which were earlier and more often arranged for political reasons. Here's a long time series for marrying in England and Wales:

There are two problems with the figure. First, it concerns all marriages not just the first. Probably most marriages were first marriages given the culture and law surrounding divorce, but some were not. Second, even if marriage was earlier, first child was not necessarily immediately after marriage. The authors explain the relevance of the findings:

Relatively late marriage in Britain and across a swath of North-West Europe is linked to something called the ‘European Marriage Pattern’. The key characteristic of this is that young couples usually set up a new household on marriage.

Establishing a new household involved the considerable expense of purchasing the cooking pots, blankets and tools they would need to equip their new home, and consequently both men and women would spend their late teens and early twenties earning money and saving some of it in preparation for marriage. Sometimes they would continue to live with their parents while doing this, but it was quite common to take a position as a domestic or farm servant which involved lodging with their employer.

This process of working and saving pushed marriage ages into the mid-twenties for both men and women. It also had the effect of making marriage responsive to the economy, as when wages were low it took longer to save for marriage, but when wages were high people were able to marry a bit earlier. In this way the long fluctuations in marriage age until about 1750 have been attributed to extended economic cycles.

The period referred to as the industrial revolution was characterised by a large increase in factory labour, and the comparatively high wages of factory work, together with the security it offered, meant that people could afford to marry at younger ages.

This (NW) European Marriage Pattern is the same thing as the Hajnal line map (after John Hajnal, a Hungarian Jew, curiously, a German Nazi called Werner Conze came up with it before):

So comparatively late marriage is not a new thing, it is the old thing. We don't know exactly how old, but the British data above suggests at least since the 1500s.

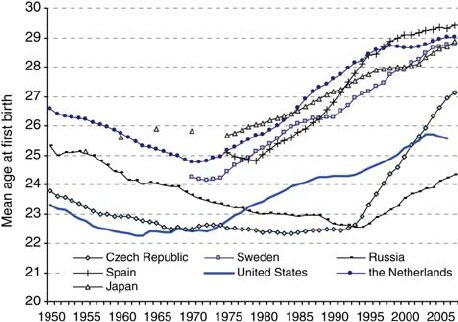

What about age of first birth specifically? Here is some comparative data:

Between the 7 countries, they don't even have the same lowest point. It looks like Russia reached their minimum only after the fall of communism around 1995, while USA reached it already in 1960, Sweden in 1972 (but hard to say for sure). Here's another time series with different countries for first marriages:

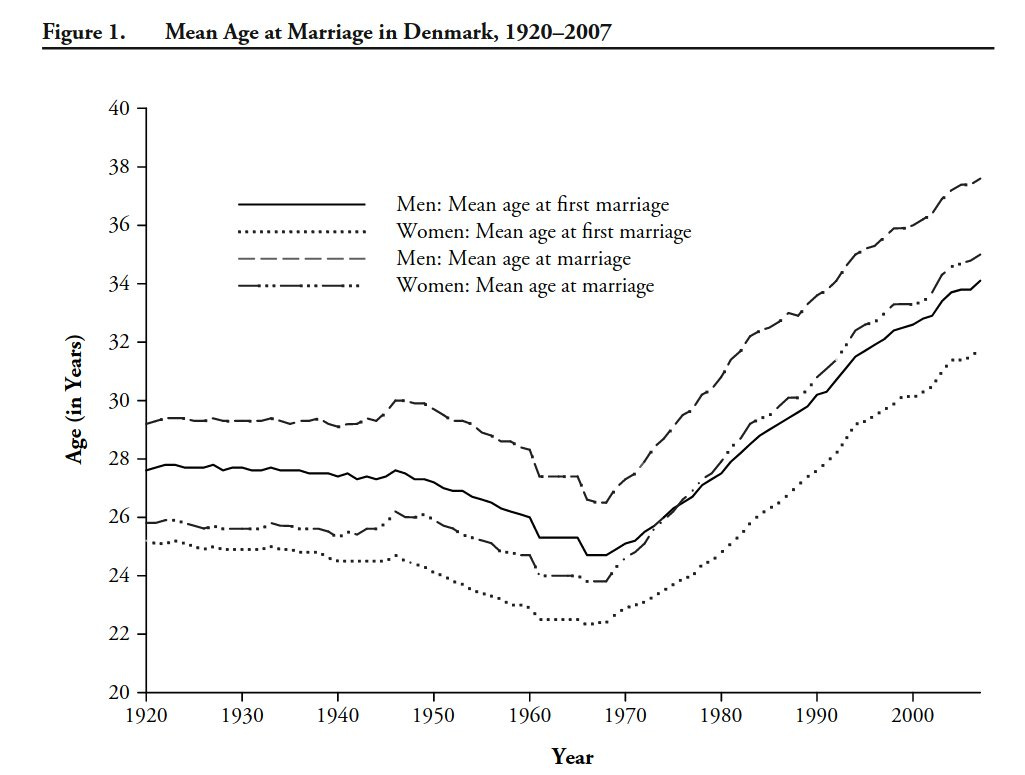

Concerning again marriage, here's Danish marriage data by first vs. all:

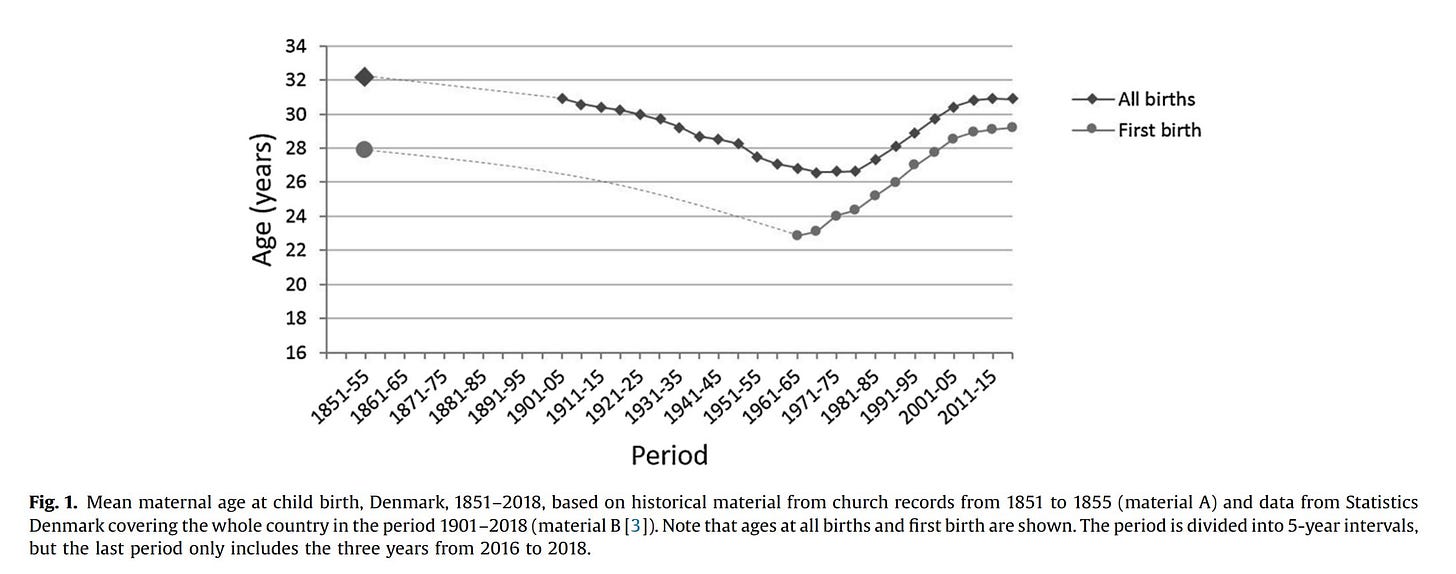

Helpfully, this time we have first marriages. Denmark reached its low point in 1967, whereas only 100 years ago, the average first marriage age for men was 28 and 25 for women. Helpfully, I found a matching time series for age of mothers:

The one datapoint from 1850 comes from a detailed study of a regional church's notes, and should be roughly representative of Denmark at the time. Assuming it is, we can see that though Danish women may have married first at around 23, their first child was usually around 26. And in 1850, the age of first birth was about the same as the modern values.

I also found marriage data for USA directly from the censuses:

Again, we see that the lowest point is around 1960, whereas in 1890, the age for women was the same as in 1980 (22, still quiet young), and 26 for men (same as in 1990). The USA is clearly an outlier compared to the European nations, probably has something to do with settler and migration culture (marry and move to the USA, or move to USA and marry someone quickly). Note also that USA has abnormally low first marriage ages for women in the 1800s (in the plot with 9 countries).

It is surprisingly difficult to find these historical time series since almost all research one finds when searching for "age at first birth" is concerned with age at first birth are medical studies that seek to show this is associated with negative outcomes. Similarly, one can look between countries and get the same result. This suggests to readers that delayed childbirth is good (and lower fertility is good, hence pressuring poor countries to adopt fertility reductions). Actually, only recently, early marriage was associated with stronger economic growth:

A decrease followed by an increase in the age of marriage was observed in the twentieth century in all advanced economies. This stylized fact is intriguing because of the non-monotonic relationship between age of marriage and economic growth. Today, a high level of economic development is associated with late marriage, but for most of the twentieth century the opposite was true: economic growth was associated with early marriage. Studies published around the middle of the century document the trend toward an earlier marriage. For example, Newcomb (1937) writes with respect to the United States that

“Today the prospect of marriage and children is popular again; 60 percent of the girls and 50 percent of the men would like to marry within a year or two of graduation… boys and girls tend to take it for granted that they will be married, as they did not a decade ago.”

Almost 35 years later, Dixon (1971) writes that

“The trend away from the ‘European’ pattern is most obvious in the wealthier nations of the West, especially in the English-speaking nations overseas and in England, France, Belgium and parts of Scandinavia. These are also countries with increasingly assertive and independent youth who are taking advantage of the opportunities to marry young that the wealthy and secure economies provide.”

The decades that followed have shown that the downward trend in the age of marriage was temporary. The age at first marriage has climbed sharply since the 1960s in the United States and advanced parts of Europe and since the 1970s and 1980s also in Southern Europe and Ireland. This upward trend reached the former Communist Eastern European countries in the 1990s.

This delayed marriage pattern in NW Europeans was because of neolocalism, the cultural pattern that newlyweds move out to a new place. Since buying or renting a place required first establishing a career, this caused some delay. However, it also caused a selection effect as not everybody could succeed in this game. Hence, we see relatively large numbers of childless women (20-25%), which is not seen in historical data from other civilizations. Thus, plausibly, neolocalism is associated with faster natural selection for traits allowing people to succeed in this game, that is, human capital. Furthermore, due to the fact that people didn't live with their relatives, their social mobility would be more mobile as they could move somewhere else to pursue a more gainful career (for the man usually). This should result in higher economic efficiency. The combination of also avoiding cousin marriages would tend to make people less inbred and less nepotistic. These patterns together probably explain the unique psychological package found in NW Europeans.

> However, it also caused a selection effect as now everybody could succeed in this game.

I'm pretty sure you meant "not" instead of "now".

Yes, North-western European culture is adapted to late marriage. Although the age of first marriage among females has never risen as sharply nor as high as over the last thirty years.

The main worry, though, is the proportion of women who never have children. That seems to be rising as sharply as the age of first marriage. (As with climate change, it is the rate of change that matters, not, within reason, the particular numbers at any one time.)

The rate of childlessness was almost the same thing as the proportion of never-married women before the development of the welfare state. Not so much any more perhaps, but there are other things driving childlessness now.

Stephen Shaw, in interviews about his research for his documentary "Birth Gap", found that the majority of childlessness was involuntary. It was due to women believing what they have been told since the 1960s, that "there is plenty of time to have children", "the twenties are for having fun; you can settle down later", and "career comes first", and similar masculine life-narratives.

In the current culture, with those narratives and a welfare state, one heritable characteristic likely to correspond with fertility is impulsiveness/poor planning ability.