Psychotics are bad, anti-psychotics are good

More people should be on high quality anti-psychotics

Remember this guy?

His name is Noah Esbensen. Actually, he is not a big deal outside of Denmark, but he made a brief stir in the media by going into a mall in Denmark and shooting people. This kind of thing happens very rarely in Denmark, so it gets a lot of attention. His kill count was terrible: 3 deaths, and at least one was a foreigner, Russian male. Esbensen doesn't appear to be very political. There's no manifesto or anything or the sort. However, he did have a Youtube channel that indicated what was to come (it was immediately censured, so we use the archived version which hasn't been censured yet):

Each video has this description (archived):

The attentive reader will see: Quetiapine doesn't work. What is Quetiapine? Wikipedia:

Quetiapine, sold under the brand name Seroquel among others, is an atypical antipsychotic medication used for the treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder.[6][7] Despite being widely used as a sleep aid due to its sedating effect, the benefits of such use do not appear to generally outweigh the side effects.[8] It is taken orally.[6]

So it's an anti-psychotic, i.e., drugs we give to people who have or are prone to psychosis. Psychosis, for those not familiar with shrink language, means:

Psychosis is a condition of the mind that results in difficulties determining what is real and what is not real.[6] Symptoms may include delusions and hallucinations, among other features.[6] Additional symptoms are incoherent speech and behavior that is inappropriate for a given situation.[6] There may also be sleep problems, social withdrawal, lack of motivation, and difficulties carrying out daily activities.[6] Psychosis can have serious adverse outcomes.[6]

So it basically means people who are schizophrenic or have a similar kind of illness, such as bipolar disorder (in the manic phase), or drug abuse of stimulants (speed/amphetamine, cocaine etc.) leading to psychosis. These people are unable to tell reality from fiction even at a very basic level. Consequently, they are very dangerous to themselves and to others.

So the Fields shooter, named after the mall he shot up, was very likely a psychotic of some sort. He openly posted videos of himself with weapons, and he was receiving but perhaps not taking, some kind of anti-psychotic medicine. Is he a bad example? Is there a relationship between psychosis, and psychotics, and crime? It's almost in the word, but there's a whole industry of academics who downplay or deny this association. Take this 2006 paper with a strange framing:

Objective: This study aimed to determine the population impact of patients with severe mental illness on violent crime.

Method: Sweden possesses high-quality national registers for all hospital admissions and criminal convictions. All individuals discharged from the hospital with ICD diagnoses of schizophrenia and other psychoses (N=98,082) were linked to the crime register to determine the population-attributable risk of patients with severe mental illness to violent crime. The attributable risk was calculated by gender, three age bands (15-24, 25-39, and 40 years and over), and offense type.

Results: Over a 13-year period, there were 45 violent crimes committed per 1,000 inhabitants. Of these, 2.4 were attributable to patients with severe mental illness. This corresponds to a population-attributable risk fraction of 5.2%. This attributable risk fraction was higher in women than men across all age bands. In women ages 25-39, it was 14.0%, and in women over 40, it was 19.0%. The attributable risk fractions were lowest in those ages 15-24 (2.3% for male patients and 2.9% for female patients).

Conclusions: The population impact of patients with severe mental illness on violent crime, estimated by calculating the population-attributable risk, varies by gender and age. Overall, the population-attributable risk fraction of patients was 5%, suggesting that patients with severe mental illness commit one in 20 violent crimes.

So really, psychosis people only commit 5% of crime. One might imagine an implicit conclusion that people need not be worried. The reader should ask: how many % of the population is in this category? What is the relative crime rate? If we read the paper, we find:

For schizophrenia, the crude odds ratio was 6.3 (95% CI=6.1–6.6), and for other psychoses, it was 3.2 (95% CI= 3.1–3.3). We calculated the population-attributable risk and the population-attributable risk fraction for these patients. A total of 26,663 individuals were discharged from the hospital with schizophrenia, and 71,419 individuals were discharged with other psychoses. The number of violent crimes committed was 328 per 1,000 patients with schizophrenia and 173 per 1,000 patients with other psychoses. The population-attributable risk for patients with schizophrenia to violent crimes was 1.0 (out of 45) per 1,000 inhabitants in the population, and for other psychoses, it was 1.4. This corresponded to a population-attributable risk fraction of 2.3% for patients with schizophrenia and 2.9% for patients with other psychoses.

So the relative rates (OR is almost the same here) are 6.3 for schizophrenics and 3.2 for the other psychotics. Those are large relative rates! Or take this 2015 paper: Refuting the Myth of the “Violent Schizophrenic”: Assessing an Educational Intervention to Reduce Schizophrenia Stigmatization Using Self-Report and an Implicit Association Test

The goal of this study was to determine whether an educational intervention designed to reduce stigmatization of individuals with schizophrenia improves implicit attitudes, in addition to the improvements in explicit attitudes that have been demonstrated in past research. Participants were 94 undergraduate students randomly assigned to one of two conditions: the experimental group received education about low rates of violence in individuals with schizophrenia; the control group read facts unrelated to mental health. Participants completed an Implicit Attitudes Test measuring unconscious attitudes about schizophrenia and violence before and after reading their assigned information; participants then reported the social distance they desired from individuals with schizophrenia. The intervention improved explicit but not implicit attitudes about schizophrenia, suggesting that educational interventions may not be sufficient to improve the lives of people with schizophrenia by reducing stigmatization against them.

Myth of the violent schizophrenic!

Or this 2019 paper: Debunking the Myths: Mental Illness and Mass Shootings

There is a pervasive assumption that mental illness equates to dangerousness and violence as it relates to mass shootings. The researchers examine the assumption and present a comprehensive literature review of how issues of mental illness impact violence and dangerousness. Many risk factors for violence are associated with mental health conditions, but they also occur in the absence of a diagnosis. A range of issues will be explored, including the unpredictability of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, stress from mental health problems inhibiting emotional stability, and past inpatient hospitalizations for suicide attempts as they impact likelihood of committing targeted violence. Risk mitigation strategies will be presented following a review of the literature.

There's also something that innocuously is called The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, which has this 2018 piece: Debunking the Myth of Violence and Mental Illness:

It is important that people come to know the facts, and end the mistaken, widespread belief that acts of violence are driven by mental illness. Studies have found that of all violent acts in the U.S., less than five percent of violence in the U.S. is attributable to mental illness. While people who commit violent acts certainly have a host of problems that lead them to become violent, in the vast majority of cases, a treatable mental illness is NOT the cause. It should also be noted that the category of mass violent acts includes domestic/family violence, which are a much more common form of violence than public mass shootings.

The same error of absolute % taken as indicator of causality or importance.

One could go on with these kind of writings, but now let's look at proper studies of the association:

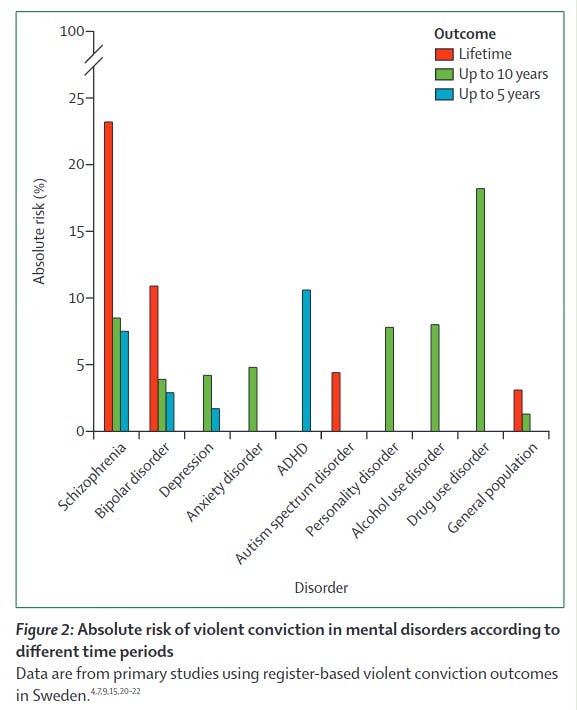

In this Review, we summarise evidence on the association between different mental disorders and violence, with emphasis on high quality designs and replicated findings. Relative risks are typically increased for all violent outcomes in most diagnosed psychiatric disorders compared with people without psychiatric disorders, with increased odds in the range of 2–4 after adjustment for familial and other sources of confounding. Absolute rates of violent crime over 5–10 years are typically below 5% in people with mental illness (excluding personality disorders, schizophrenia, and substance misuse), which increases to 6–10% in personality disorders and schizophrenia spectrum disorders, and to more than 10% in substance misuse. Past criminality and comorbid substance misuse are strongly predictive of future violence in many individual disorders. We reviewed national clinical practice guidelines, which vary in content and require updating to reflect the present epidemiological evidence. Standardised and clinically feasible approaches to the assessment and management of violence risk in general psychiatric settings need to be developed.

Here we see a meta-meta-analysis by mental illness category. The value we care the most about is the diagnosis vs. general population. All the values are starkly elevated except for autism. Unsurprisingly, autistics are not generally considered violent. Rather they tend to be stay-at-homers and not do much of anything related to other humans. For schizophrenia, bipolar, depression and ADHD, we see quite high rates of: 5-8x, 5x, 3x, and 4x. The sibling studies are interesting for causality, but as we know that siblings who lack a diagnosis generally speaking high on the underlying trait, these comparisons don't tell us about the full causality of a person with a diagnosis vs. a representative person without a diagnosis. Still, they are all positive, so the causality is hard to get around. Not that many ordinary people (not academics) would question that causality is craziness -> violence.

The second plot has more diagnoses, but has risk over time instead of relative rates. We see that the life-time risk of violent crime for the general population is something like 3.5%. For schizophrenics it is 23%, so the rate is about 6.6x by eye-balled math. A such high rate is nothing to scruff at. Almost a 1 in 4 chance when you meet a such person they will be convicted for violent crime at some point in their life! Maybe a normal people would decide not to take their chances. For bipolar, the lifetime risk is still about 11%, or 1 in 9 people. There was no lifetime risk study for ADHD, but already after 5 year, it hit about 11%, so the lifetime risk must be fairly high. Actually, their 5 year risk was higher than the schizophrenics, so these numbers imply ADHDers are higher risk than the schizophrenics. But was that not the case in the first figure, so I assume it has to do with differences between the studies. People who abuse substances are also particularly dangerous, their rate is higher than schizophrenics after 5 years, and it may be true. Stay away from drug abusers, especially of alcohol and stimulants. People with the more ordinary illnesses of depression and anxiety seem to be about 2x risk of the general population, so not too much reason to worry.

The year after, in 2021, there was a systematic review of schizophrenia-like disorders and violence: Association of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders and Violence Perpetration in Adults and Adolescents From 15 Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Importance Violence perpetration outcomes in individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders contribute to morbidity and mortality at a population level, disrupt care, and lead to stigma.

Objective To conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the risk of perpetrating interpersonal violence in individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders compared with general population control individuals.

Data Sources Multiple databases were searched for studies in any language from January 1970 to March 2021 using the terms violen* or homicid* and psychosis or psychoses or psychotic or schizophren* or schizoaffective or delusional and terms for mental disorders. Bibliographies of included articles were hand searched.

Study Selection The study included case-control and cohort studies that allowed risks of interpersonal violence perpetration and/or violent criminality in individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders to be compared with a general population group without these disorders.

Data Extraction and Synthesis The study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines and the Meta-analyses of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) proposal. Two reviewers extracted data. Quality was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale. Data were pooled using a random-effects model.

Main Outcomes and Measures The main outcome was violence to others obtained either through official records, self-report and/or collateral-report, or medical file review and included any physical assault, robbery, sexual offenses, illegal threats or intimidation, and arson.

Results The meta-analysis included 24 studies of violence perpetration outcomes in 15 countries over 4 decades (N = 51 309 individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders; reported mean age of 21 to 54 years at follow-up; of those studies that reported outcomes separately by sex, there were 19 976 male individuals and 14 275 female individuals). There was an increase in risk of violence perpetration in men with schizophrenia and other psychoses (pooled odds ratio [OR], 4.5; 95% CI, 3.6-5.6) with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 85%; 95% CI, 77-91). The risk was also elevated in women (pooled OR, 10.2; 95% CI, 7.1-14.6), with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 66%; 95% CI, 31-83). Odds of perpetrating sexual offenses (OR, 5.1; 95% CI, 3.8-6.8) and homicide (OR, 17.7; 95% CI, 13.9-22.6) were also investigated. Three studies found increased relative risks of arson but data were not pooled for this analysis owing to heterogeneity of outcomes. Absolute risks of violence perpetration in register-based studies were less than 1 in 20 in women with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and less than 1 in 4 in men over a 35-year period.

Conclusions and Relevance This systematic review and meta-analysis found that the risk of perpetrating violent outcomes was increased in individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders compared with community control individuals, which has been confirmed in new population-based longitudinal studies and sibling comparison designs.

So in other words: rape was about 5x risk, homicide (murder etc.) was a whopping 18x risk! The more severe the crime, the higher the relative risk. This is because of the nature of extreme crimes and normal distributions. Let's illustrate this with... global warming:

So as the average temperature goes up, we get much higher chances to hit extremely hot temperatures. The higher we set the threshold for "extremely hot", the higher the relative rate of a normal distribution with a higher mean. In crime terms, we can think of an individual as having a criminal disposition. Each day, we pick a random value from that person's distribution. When a value is above some threshold, we get a minor crime. When it is above the next threshold, we get a more severe crime. When it is above a really high threshold, we get an extreme crime, like a mall shooting, or a cop killing rampage. Thus, if we compare normal people vs. people with very high crime dispositions, the more extreme the threshold we pick -- the more extreme crime type we look at -- the more extreme will be the relative rates. So for homicide above, we saw a risk of 18x, i.e., 1700% more like, whereas for any ordinary violent crime, it may be only +500%. This model of thinking about things is general, and also works when comparing immigrant groups, racial groups etc., the differences are larger for murder rates than for shoplifting. Of course, this same model holds for positive outcomes too. For IQ/height/etc, you can play around with the values with this simulator.

What about treatment?

What can we do about these people? The rate of schizophrenia appears to be about 1% of the population across time, relatively stable. So we have had to deal with these people for decades. I would guess the traditional solution was to lock them up in mental hospitals and try to forget about them. We now consider this somewhat too inhumane, so we do the next best thing: we give them drugs that basically make them docile (and fat). The question is whether these drugs work or not. Danish spree shooter Esben says the one he took doesn't work. Is he right?

Sariaslan, A., Leucht, S., Zetterqvist, J., Lichtenstein, P., & Fazel, S. (2021). Associations between individual antipsychotics and the risk of arrests and convictions of violent and other crime: a nationwide within-individual study of 74 925 persons. Psychological medicine, 1-9.

Background: Individuals diagnosed with psychiatric disorders who are prescribed antipsychotics have lower rates of violence and crime but the differential effects of specific antipsychotics are not known. We investigated associations between 10 specific antipsychotic medications and subsequent risks for a range of criminal outcomes.

Methods: We identified 74 925 individuals who were ever prescribed antipsychotics between 2006 and 2013 using nationwide Swedish registries. We tested for five specific first-generation antipsychotics (levomepromazine, perphenazine, haloperidol, flupentixol, and zuclopenthixol) and five second-generation antipsychotics (clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and aripiprazole). The outcomes included violent, drug-related, and any criminal arrests and convictions. We conducted within-individual analyses using fixed-effects Poisson regression models that compared rates of outcomes between periods when each individual was either on or off medication to account for time-stable unmeasured confounders. All models were adjusted for age and concurrent mood stabilizer medications.

Results: The relative risks of all crime outcomes were substantially reduced [range of adjusted rate ratios (aRRs): 0.50-0.67] during periods when the patients were prescribed antipsychotics v. periods when they were not. We found that clozapine (aRRs: 0.28-0.44), olanzapine (aRRs: 0.46-0.72), and risperidone (aRRs: 0.53-0.64) were associated with lower arrest and conviction risks than other antipsychotics, including quetiapine (aRRs: 0.68-0.84) and haloperidol (aRRs: 0.67-0.77). Long-acting injectables as a combined medication class were associated with lower risks of the outcomes but only risperidone was associated with lower risks of all six outcomes (aRRs: 0.33-0.69).

Conclusions: There is heterogeneity in the associations between specific antipsychotics and subsequent arrests and convictions for any drug-related and violent crimes.

So what they do is compare the same persons when they are on treatment and when they are not. This within-person design avoids genetic confounding and stable environmental factors (e.g. childhood abuse). Since we know these are the main sources of variance for violent crime between persons (and another one with just twins), the remaining variation that we can link to a drug is probably largely causal. The values in the abstract have to be read as ‘smaller is better’ because 1.00 is a reduction of 0.00. So really, just read the values as 1-value for the reduction %. In a figure:

On the right side, we see the relative rates. The grey results are from the between-person analysis with all the genetic and shared environmental biases included. The red results are from within-person analysis. In those we see about 50% reduction in crime rate overall, i.e., across the different anti-psychotics.

Finally, in this plot, we see a rank ordering of the different anti-psychotics. Esben said that Quetiapine sucks, and the results agree: among the 13 examined drugs, it was in the 11th spot. I guess we should be giving them Clozapine. The question is why was Esben on this third rate treatment? I am told that Clozapine has terrible side effects and that's why clinicians prefer to prescribe the other ones (at least at first). However, the most pressing question here is: how much should society care about the side effects of treatments for schizophrenics compared to reducing to their damage to other citizens? If one only thinks about side effects on the user and not efficacy, that is the same as saying that the well-being of other people doesn't matter at all compared to the schizophrenics. I think it is most sensible to prioritize the well-being of ordinary citizens. Maybe the case of the Esben can force some people to think more carefully about this decision.

tangentially, we should consider lock up to avoid damaging others in some cases.

ie violent psychotics refusing treatment, Isis graduates, Mafia bosses.

Research how many mass shooters are on anti-depressants, esp. SSRIs, known to produce emotional numbness. The German pilot who flew SwissAir into a mountain was depressed, not just about his relationship break-up, but about his failing eyesight. They gave him more anti-depressants, known to have adverse effects on the eyes, so he got more depressed and more emotionally numb. The result was predictable. At the time, it was said that Transport Canada was still allowing pilots on these Rx pills to fly..... Such is the power of Pharma.