"public policy never necessarily follows from scientific findings", yes and no

How does one convince the public to support eugenics?

I am currently reading Bryan Caplan's new book collection of old blogposts in book format. One of them was pretty interesting: Behaviorial Geneticists versus Policy Implications from 2009. He quotes Plomin et al's textbook as saying:

The idea of genetic contribution to g has produced controversy in the media, especially following the 1994 publication of The Bell Curve by Herrnstein and Murray (1994). In fact, these authors scarcely touched on genetics and did not view genetic evidence as crucial to their arguments. In the first half of the book, they showed, like many other studies, that g is related to educational and social outcomes. In the second half, however, they attempted to argue that certain conservative policies follow from the findings. But, as discussed in Chapter 18, public policy never necessarily follows from scientific findings; and on the basis of the same studies, it would be possible to present arguments that are the opposite of those of Herrnstein and Murray.

Caplan's criticism is that: surely this is obvious. Policy recommendations always follow from some joint set of factual premises and some moral ones. Plomin et al is avoiding talking about the implications of their field's central findings because:

So why are behavioral geneticists so eager to downplay the practical relevance of their field? The most plausible explanation is that these scientists already have enough trouble with political correctness. They don’t want to amplify their public relations problem by pointing out that their science undermines a bunch of popular, feel-good policies.

Caplan was quoting the 5th edition, published in 2008. We are currently on the 7th edition, from 2018. I, uh, acquired a copy of it, and this passage no longer exists. There is still some brief mention of The Bell Curve though:

During the 1960s, environmentalism, which had been rampant until then in American psychology, was beginning to wane, and the stage was set for increased acceptance of genetic influence on g. Then, in 1969, a monograph on the genetics of intelligence by Arthur Jensen almost brought the field to a halt because a few pages in this lengthy monograph suggested that ethnic differences in IQ might involve genetic differences. Twenty five years later, this issue was resurrected in The Bell Curve (Herrnstein & Murray, 1994) and caused a similar uproar. As we emphasized in Chapter 7, the causes of average differences between groups need not be related to the causes of individual differences within groups. The former question is much more difficult to investigate than the latter, which is the focus of the vast majority of genetic research on IQ. The storm raised by Jensen’s monograph led to intense criticism of all behavioral genetic research, especially in the area of cognitive abilities (e.g., Kamin, 1974). These criticisms of older studies had the positive effect of generating bigger and better behavioral genetic studies that used family, adoption, and twin designs. These new projects produced much more data on the genetics of g than had been obtained in the previous 50 years. The new data contributed in part to a dramatic shift that occurred in the 1980s in psychology toward acceptance of the conclusion that genetic differences among individuals are significantly associated with differencesing (Snyderman & Rothman, 1988).

Elsewhere they repeat the same no policies follow line:

Although it is useful to think about what could be, it is important to begin with what is — the genetic and environmental sources of variance in existing populations. Knowledge about what is can sometimes help guide research concerning what could be, as in the example of PKU, where the effects of this single-gene disorder can be blocked by a diet low in phenylalanine (Chapter 3). Most important, heritability has nothing to say about what should be. Evidence of genetic influence for a behavior is compatible with a wide range of social and political views, most of which depend on values, not facts. For example, no policies necessarily follow from finding genetic influences or even specific genes for cognitive abilities. It does not mean, for example, that we ought to put all our resources into educating the brightest children. Depending on our values, we might worry more about children falling off the low end of the bell curve in an increasingly technological society and decide to devote more public resources to those who are in danger of being left behind. For example, we might decide that all citizens need to reach basic levels of literacy and numeracy to be empowered to participate in society. [page 100]

...

Finding genes that account for the heritability of cognitive abilities has impor tant implications for society as well as for science (Plomin, 1999). The grandest implication for science is that these genes will serve as an integrating force across diverse disciplines, with DNA as the common denominator, and will open up new scientific horizons for understanding learning and memory. In terms of implications for society, it should be emphasized that no public policies necessarily follow from finding genes associated with cognitive abilities because policy involves values (see Chapter 20). For example, finding genes that predict cognitive ability does not mean that we ought to put all of our resources into educating the brightest children once we identify them genetically. Depending on our values, we might worry more about the children falling off the low end of the bell curve in an increasingly technological society and decide to devote more public resources to those who are in danger of being left behind. [page 190]

So Plomin et al were perhaps reading Caplan's blogpost as the new version definitely was updated on this matter and in line with what Caplan might have suggested on a nice day. The book now doesn't even mention any supposed conservative policy implications.

We can go further though. As I argued in my policy outline, really, our policies ought to be affected by what science says. No one really disagrees with this. The main benefit of science is that it is a guide to action. If social science was as truthful as physics it would provide good recommendations for policies. Alas, social science is mainly false or misleading for a variety of reasons (see e.g. this discussion by eminent work psychologist Frank Schmidt). That aside, we may still gauge whether people appear to be rationally affected by their factual beliefs with regards to policies on the topic. That is, people who believe facts about the genetic influence on traits, or the lack thereof, do they also hold policy opinions that fit? When Caplan was writing in 2009, there was perhaps no research on this. But Zigerell 2020 looked into this matter in his paper Understanding public support for eugenic policies: Results from survey data:

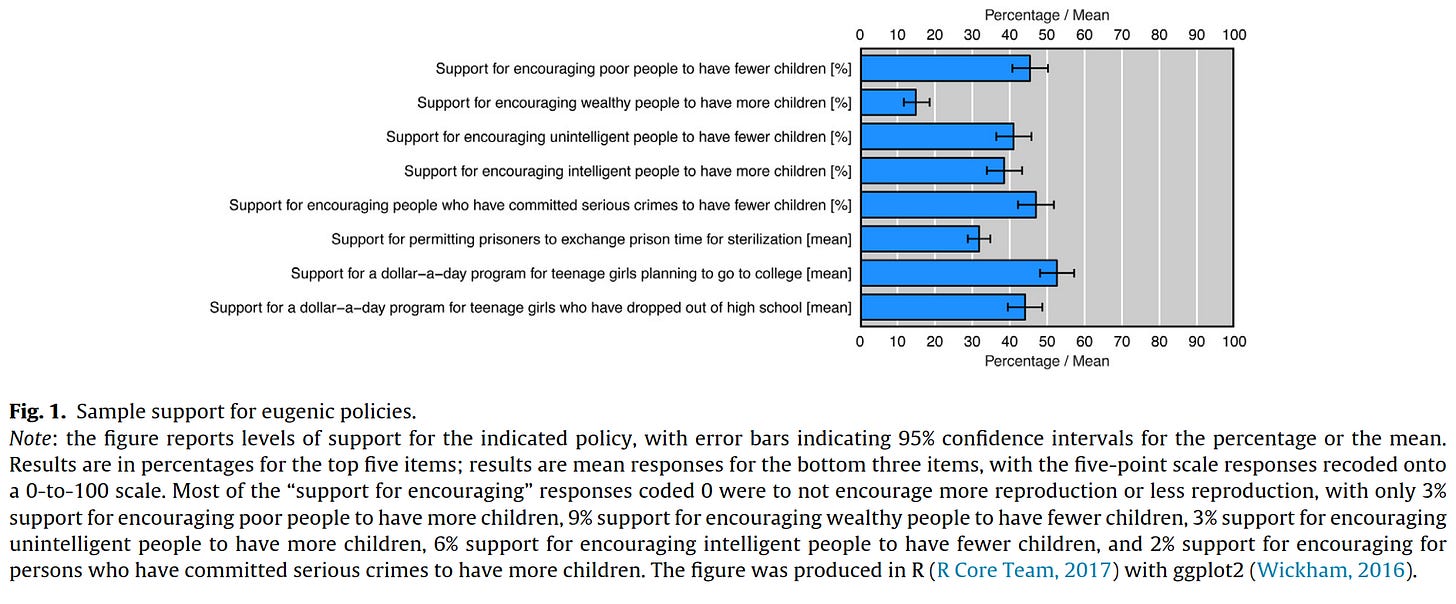

Little published empirical research has investigated public support for eugenic policies. To add to this literature, a survey on attitudes about eugenic policies was conducted of participants from Amazon Mechanical Turk who indicated residence in the United States (N > 400). Survey items assessed the levels and correlates of support for policies that, among other things, encourage lower levels of reproduction among the poor, the unintelligent, and people who have committed serious crimes and encourage higher levels of reproduction among the wealthy and the intelligent. Analyses of responses indicated nontrivial support for most of the eugenic policies asked about, such as at least 40% support for policies encouraging lower levels of reproduction among poor people, unintelligent people, and people who have committed serious crimes. Support for the eugenic policies often associated with feelings about the target group and with the perceived heritability of the distinguishing trait of the target group. To the extent that this latter association reflects a causal effect of perceived heritability, increased genetic attributions among the public might produce increased public support for eugenic policies and increase the probability that such policies are employed.

The main results are telling:

So overall, there was widespread support for eugenic policies, with one of them even reaching a slight majority (the error bar crosses 50%, so we don't really know). It is certainly false that public support for eugenic policies is fringe or rare. As a matter of fact, the sample here was an unrepresentative sample of US MTurkers, which means more young and left-wing people than the American general population, so this will understate the level of support.

The second plot shows the model regression results, read the caption to understand the method. In each case we see a linear pattern so that the higher people thought the heritability of X (e.g. crime) was, the more likely they were to support a eugenic policy related to that (e.g. sterilization in exchange for earlier release). We can then rephrase Caplan's complaint. Given that Plomin et al were aware of how the public might reasonably interpret the findings, they are able to predict the probable policy implications of making the findings more well known (ASSUMING causality!). It is thus somewhat of a cop out to just say that there are no necessarily implications of the research findings.

The issue with this kind of complaint is that it is too easy. Should we require every researcher team who writes a textbook to specify how they thought the people were to change their policies if their results were more widely known? That seems silly. I also think this plays into the hands of the communist/woke activists, who are always attacking behavioral geneticists for exactly this reason. They too think that the public would favor more eugenic and conservative policies if the findings of the field were more widely known. As such, they think it is important to discredit the field, prevent more findings through a variety of means such as attacking researchers for being racist, trying to get funding removed etc. As a matter of fact, these attacks have increased in frequency on Plomin. As such, if behavioral geneticists were to be more up front about what they thought the public's reactions to their findings would be, Woke activists would have a field day. "Aha, finally, the truth finally comes out! This is not a real scientific field, but merely fake science meant to support the austerity policies of Donald Drumph!". And don't try a both-sides-ism argument. We know perfectly well that leftists always get to speculate on possible public policy implications in their papers (challenge: try to find a paper that advocates a conservative policy). That's because social science is implicitly, and sometimes explicitly, left-wing. I don't really think scientists should be speculating on the policy implications in their works. It should be a lot more "just the facts ma'am" autistic style. We don't need more politics in science, we need a lot less.

"We don't need more politics in science, we need a lot less."

No. The point of doing all of this work is to achieve policy outcomes. Knowledge that doesn't impact the world is useless. What's the point of publishing The Bell Curve if not to influence policy!

The problem is that your enemies are defeating you politically despite being wrong. That's a political problem to solve, not run away from. Running hasn't accomplished anything or made your opponents any less insane.

If for instance the science has something to say about education policy, pass some damn laws. People HATE public education right now. Arizona just passed universal school choice. San Fransisco just recalled school board members that tried to get rid of merit. We need a little less "there are no policy implications" and a little more Chris Rufo out there.

I've never seen more support for big child tax credits either. Are these things going to be eugenic (go up to $400k like the Romney plan) or dysgenic (cap at like $75k or whatever under one of those Dem proposals). If the science has something to say, say it. Show at least as big a balls as Elon Musk on this.

Crime...let's just say that people really hate crime now and would like some straight shooting on the matter.

One could go on. There are implications of this research and people shouldn't be afraid to say it. The purpose of scientific research is to improve society by changing he way we live, not to publish papers and have no effect.

"Aha, finally, the truth finally comes out! This is not a real scientific field, but merely fake science meant to support the austerity policies of Donald Drumph!".

Then just push through unapologetically. You aren't trying to convince progressives that use the word Dumpf! And austerity is just another word for fighting inflation these days, turns out it's politically popular now.

You are trying to convince normies who would benefit from your policies. They respond to strength, confidence, and results.

"For example, we might decide that all citizens need to reach basic levels of literacy and numeracy to be empowered to participate in society."

People capable of reaching basic levels of literacy and numeracy usually do so before high school. And it doesn't take the 29k/year/pupil that NYC public schools spend to teach basic literacy and numeracy.

Back in the Stone Age of say the 1960s, we had universal education of basic literacy and numeracy of all those capable of doing so that was provided for 1/3 the cost per capita in real terms with far less administrative bullshit and far better school discipline (probably even worse numbers for places like NYC).

Yes, teaching basic literacy and numeracy to the dims would still pass an ROI calculation in Based Eugenistan, but that doesn't mean research into genetics wouldn't imply massive changes from the policy status quo.