Science vs. ideology on vertical transfers

Meta-analysis shows vertical transfer on average accounts for ~1% of variance

Last year Marcus Feldman and Kevin Lala published one of those anti-hereditarian pieces:

Lala, K. N., & Feldman, M. W. (2024). Genes, culture, and scientific racism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(48), e2322874121.

Quantitative studies of cultural evolution and gene-culture coevolution (henceforth “CE” and “GCC”) emerged in the 1970s, in the aftermath of the “race and intelligence quotient (IQ)” and “human sociobiology” debates, as a counter to extreme hereditarian positions. These studies incorporated cultural transmission and its interaction with genetics in contributing to patterns of human variation. Neither CE nor GCC results were consistent with racist claims of ubiquitous genetic differences between socially defined races. We summarize how genetic data refute the notion of racial substructure for human populations and address naive interpretations of race across the biological sciences, including those related to ancestry, health, and intelligence, that help to perpetuate racist ideas. A GCC perspective can refute reductionist and determinist claims while providing a more inclusive multidisciplinary framework in which to interpret human variation.

The piece itself is not particularly interesting. We can sum it up by saying that 1) the authors want others to use ill-defined gene-culture models they advocate, 2) people who investigate genetic causes are bad racists. The present the following intuitive line of argument which they consider wrong:

People can use skin color and other easily observed anatomical features to allocate individuals to racial categories. These physical differences have a genetic basis, so it is easy to imagine that they are representative of human biology, and that genetic differences between races extend to less-visible characteristics, including temperament and mental ability. In addition, ancestry analyses, confirm that there are genetic differences between populations, while the medical community uses race as a disease-risk criterion, and links differences between populations to the incidence of medical conditions (e.g., stroke, heart disease). The dominance of particular races in some sports, and variation across races in scholastic performance, educational attainment, and IQ, is interpreted as reflecting biological differences. As a result, the assertion that races are social constructs may be regarded with suspicion, and viewed as politically motivated.

One might instead say that it’s a pretty accurate description of findings. They don’t actually cite evidence against it, just say it is incorrect. After that they spend pages on summarizing the history of the eugenics movement in the 1900s (yawn). Anyway, their article makes some obvious blunders such as invoking the Flynn effect to show that Jensen’s variance argument was incorrect. Actually, Flynn effects are a violation of measurement invariance across time, so the effect, while interesting, is not relevant to Jensen’s variance argument. Better for them would be to point out that human height can increase over time despite high heritabilities, but then again, Jensen was talking about same-time differences between groups, not across-time differences within-groups. They are wrong, anyway, about the lack of a link between heritabilities of phenotypes and modifiability.

It turns out there is no further need to point out the numerous errors because a paper was just published doing this:

Figueredo, A. J., Peñaherrera-Aguirre, M., & Woodley of Menie, M. A. (2025). Obsolete Science and Egalitarian Meta-political Activism in Contemporary Gene-Culture Coevolution: A Response to Lala and Feldman (2024). Evolutionary Psychological Science, 1-24. PDF

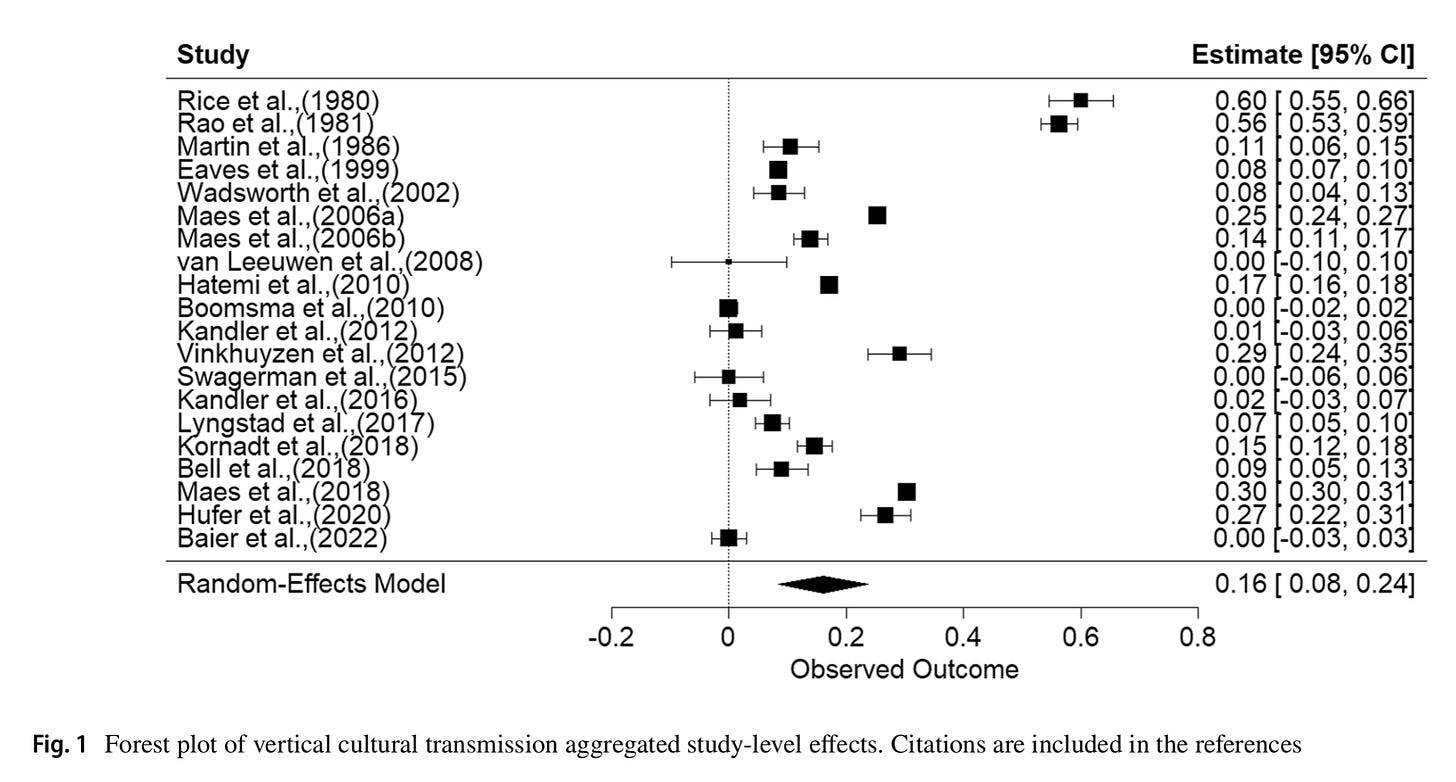

We counter two broad claims offered by Lala and Feldman (L&F) in support of what they call Contemporary Gene-Culture Coevolution (CGCC): (1) Cultural transmission pathways confound and inflate heritability estimates for a range of traits: This is tackled via a meta-analysis of behavior-genetic studies that estimate vertical cultural transmission effects on trait variance for a wide variety of phenotypes. We find that this pathway plays only a very small role (relative to genetic effects) in conditioning phenotypic variance. (2) GCC only works narrowly on functionally well-circumscribed genes; in the case of complex polygenic traits drift mechanics prevent the emergence of population differences as there is an extremely low probability of coherence involving drift direction across many genes favoring (in terms of associated trait means) one population over another; purely cultural forms of evolution are therefore sufficient to account for cross-cultural variability in the means of certain traits: We conduct a cross-cultural sociogenetic analysis of the causes of variation in life history characteristics and find indications that culture-gene coevolution (but not purely cultural evolution) best describes the distribution of these traits. Drift is also ruled out as a cause of the underlying genetic variegation among our units of analysis. Multiple other contrary lines of evidence are also reviewed in light of the biocultural dynamics research program, which we posit as an alternative to CGCC. We also highlight meta-political activism latent in L&F’s selection and interpretation of evidence, concluding that this risks anti-scientific censorship and fails to address the political issues that concern them.

This paper has a few paths: 1) attacking the errors in L&F, 2) actually presenting a meta-analysis of vertical transfer effects from the existing literature, 3) presenting some research using their preferred gene-culture co-evolution model. Vertical transfer is a parameter that cannot be estimated separately in classical twin designs (it is part of the shared environment), but it can be estimated in extended family designs. Recall that shared environment include any non-genetic causes that make family members more similar, and thus includes parent-to-child, child-to-parent, and sibling-to-sibling causes. The vertical transfer is the degree of similarity caused by non-genetic means between parents and children, in either causal direction (child to parent is possible, and plausible in some cases, e.g. parenting behaviors respond to child behavior). They cite some theoretical work from the 1970s and 1980s which was wrong. Anyway, so Figueredo et al used my review of vertical transfer studies from 2018 and augmented it into a real quantitative meta-analysis. Amusingly, they noted this but without giving the reference:

Another researcher has conducted a comprehensive qualitative review of this (not especially extensive4) literature, which currently spans 14 studies

published between 1986 and 2020, all of which we use in the present meta-analysis. [Footnote 4 is not relevant]

I imagine citing a blogpost by Emil Kirkegaard might have reduced their chances of acceptance during peer review, so it is common for these kinds of citations to go missing. We also know that people like Stuart Richie tell authors to remove references to disliked sources during peer review. Naughty!

Anyway, they produced this plot of vertical transfer effects across different phenotypes (intelligence was one of them, but also others):

The Rice and Rao studies from the 1980s used the wrong methods which is why they are large outliers. In their words:

A regression test for funnel plot asymmetry was per-formed using the regtest function (t = -0.906, p = 0.3768).A trim-and-fill analysis suggested the absence of five studies on the right side of the funnel plot’s center line, as indicated in Fig. 2. The recomputed effect for vertical cultural transmission slightly increased in magnitude, but remained small (zr = 0.213, se = 0.038, p < 0.0001; r = 0.210, R2 = 0.044) and was also associated with high levels of heterogeneity (Q = 4043.372, p < 0.0001). Overall, these results indicate that vertical cultural transmission explains between 2.5 and 4.4% of the variance in human attitudinal, cognitive, and personality traits. This effect is inflated by the inclusion of Rice and colleagues (Rice et al., 1980) and Rao and colleagues (Rao et al., 1982), which are clear visual outliers. Consistent with this, the removal of these two studies reduces the aggregate effect size (zr = 0.115, se = 0.025, p < 0.0001; r = 0.115, R2 = 0.013). Rerunning the trim-andfill test indicated no missing studies after removing these outliers, these results are featured in Fig. 3.

Note that the values in the plot are square roots of variances (standardized paths). As such, the average effect for vertical transfer across the 60ish reported effects was r = 0.12, or 1.3% variance. Clearly, vertical transfer is not generally a big deal. This is the same conclusion reached by an earlier review from 2004 (Richerson & Boyd 2004):

Results from several independent studies suggest that cultural transmission within the family is not very important; the similarity between parents and offspring is mainly due to genes. If these results stand up and generalize to other sorts of characters, then it would tell us that parents are less important in cultural transmission than many people suppose.

Figueredo et al like to do complex path models, and they present some results along those lines. These kinds of models have endless researcher degrees of freedom, so I don’t like them much (not even my own!). Anyway, the general problem with studying actual gene-culture co-evolution is that we don’t generally have long-running datasets of cultural measures. There were no surveys in the 1500s, nor even the 1700s (Galton pioneered questionnaires in the late 1800s). One is thus reduced to relying on indirect cultural measures like burials, religious relics, marriage patterns (insofar as these can be estimated from genetics and historical sources). It is no wonder that the favorite example of gene-culture co-evolution is lactase persistence (milk tolerance) since this depends on a single gene (variant), which is easy to track over time, as is the number of milk-producing animals people kept (from their bones). The evolution of polygenic traits is more difficult.

As is typical with these kind of Feldman papers, they are full of woke blah blah:

The term racism and cognates appear 21 times in the main text of L&F’s paper, the word even being included in the title. Racism per se is never defined concretely anywhere in the text of their article. This strategic vagueness permits the casting of shade over any idea or concept that does not sit well with the egalitarian ideological views of the authors. That these authors are committed egalitarians is clear from a plain reading of their essay. They proclaim that thinking of race and racial differences in any reductively biological sense, or even entertaining ideas that could lead to such reductively biological thinking, is dangerous as “inequities in power and wealth could be (falsely) cast as natural and inevitable” (p.8), and yet they prevaricate on the issue of the actual harms stemming from a mere belief in “natural inequality,” alluding simply to “racism and hate crimes” being “on the rise” (p.1), the only reference given here being to a book written by a left-wing journalist.

Amusingly, Figueredo et al school them on Fst’s, which is helpful since this claim keeps getting repeated:

Fst (also termed the fixation index) is not and has never been used as a basis for ascertaining the existence of subspecies, a strictly taxonomic category. Traditionally visual sorting approaches by phenotype, such as the 75% rule, have been used to taxonomically validate subspecies. This rule is based on the idea that a prospective subspecies is taxonomically valid only when ≥ 75% of those organisms comprising it fall outside 99% of the range of variation for a given trait, or set of traits, when compared to a second grouping in the same species (Patten & Unitt, 2002).

Fst therefore has nothing to do with the identification of subspecies, it does however describe the degree to which loci are differentiated at the level of population structure as opposed to at the level of individuals and functions analogously to group and individual level partitioning in ANOVA type models. Low values indicate no differentiation (such as in the case of a panmictic population), and high values indicate the presence of great differentiation, with such populations being organized into discrete subgroups. When Sewall Wright (1978) developed this metric, he proposed that values between 0.15 and 0.25 be used as the basis for determining the presence of moderately great levels of population subdivision. Contrary to what is claimed by L&F an Fst > 0.25 is not and never has been a criterion for accepting the existence of “population subgroups” which they seem to imply would count as subspecies. This peculiar claim originated in a paper by Alan Templeton published in 1998 (Templeton, 1998), having since gone on to become something of a scientific urban legend. Wright (who believed that humans were polytypic purely on the basis of visual classification5) notes also that “[d] ifferentiation is, however, by no means negligible if [Fst] is as small as 0.05 or even less” (p.85, italics for emphasis). This is because small numbers of highly polymorphic loci varying at only a few sites in the genome can generate substantive differentiation, even when Fst is low (see Coyne, 2010, Ch. 8).

While Fst cannot be used to establish the presence of taxonomic subspecies, it is nonetheless notable that there are several species whose Fst values have been found to be lower than or within the range of values reported for humans by L&F (0.052 to 0.083), but which are nevertheless considered to be taxonomically polytypic (again based on visual classification). Examples include the Canadian Lynx (Lynx canadensis, autosomal Fst = 0.033, Schwartz et al., 2002), K = 3 subspecies (according to at least some taxonomists, see Wozencraft, 2005), and the African Buffalo (Syncerus caffer, autosomal Fst = 0.059, Van Hooft et al., 2000), K = 5 subspecies. Trying to argue against the idea that humans are polytypic on the basis of their modest Fst value is flawed and can easily backfire, as illustrated by the aforementioned examples. To reiterate, Fst is not used as grounds for identifying subspecies. That errors of this sort permeate L&F’s essay does not help their case in any way.

I think John Fuerst was the first to point out this Templeton error, so let’s call it Templeton’s fallacy. It is also commonly committed by woke philosophers.

There is in fact a good study waiting to be done here. Compile the (autosomal) Fst values (or other genetic heterogeneity metrics) by species and the numbers of subspecies/races that are recognized. Humans are probably fairly typical in the degree of genetic differentiation. We are only weird in that for political reasons, it is inconvenient to acknowledge the subspecies. One would think this would be a powerful argument for the preservation of diversity!

In the spirit of history, I should like to note that Feldman is an old-school coauthor with Richard Lewontin, who was openly communist and thought science should be interpreted through communist lenses (Not in Our Genes). Given Feldman’s writings that last few years, it would appear he holds similar antiquated views.

These ideologues have been making such bogus arguments, complete with adjectives like racist, for as long as I've been around, and no doubt will be making them 50 years from now...My study of the tens of millions of SAT scores from the 1960s refutes their claims in great detail.....At least as far as intelligence and math ability are concerned....

Your Substack is of great value, and people should pay you, as I do.