The benefits of marriage

Your wife helps you be a better man

If we have to name the single largest problem with social science in itself it is that of confounding (in real-life social science, the bigger issue is probably statistical cheating with p-hacking, selective reporting and publication bias). We have tons of data from surveys and government registers, but when we examine it and find that two things are statistically related, how do we know this association is not merely statistical, but causal in nature? Finding causes of things is the main goal because making good decisions depends on knowing causes for the most part. It's far too easy to come up with a plausible sounding mechanism for any observed association, so this cannot be much evidence of causality. Jonatan Pallesen has been promoting this useful meme for pointing out confounding in common claims:

That is, we can visually point out the likely confounding variable, in this case, a shared cause. You can make memes from this template here.

Today I wanted to talk about some neat studies that mostly get around the problem of confounding. Decades of research in social science show that the main causes of outcomes of interest are stable to an individual person over time. Chiefly, this is because they are genetic in origin and thus fixed at conception, but even those that are not genetic tend to be quite stable over time. Because of this stability of causes for an individual, one very good way to avoid most of the possible confounders is to compare the same persons at different points in their lives when some hypothesized causal factor has changed. I've previously given a summary of such studies, which you can find here, but here I want to emphasize those related to marriage. American conservatives like to point out these facts:

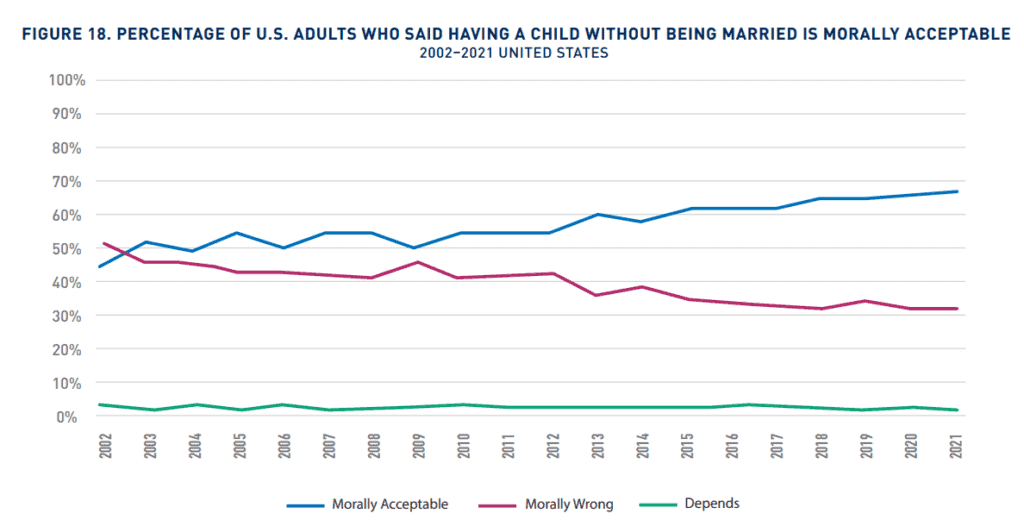

There is a stark increase in 'out of wedlock' (outside marriage) births, especially in Blacks. This relates to what they consider moral decline:

And such out of marriage births are related to worse outcomes for the children:

The effect of married fathers on child outcomes can be quite pronounced. For example, examination of families with the same race and same parental education shows that, when compared to intact married families, children from single-parent homes are:

But we also should be wary of confounding. Who has children inside and outside of marriage is certainly not random, and whatever the causes are, they are probably heritable personality traits that will be passed on to the children. It is thus unsurprising that such children have worse outcomes purely for genetic reasons. We can thus apply the meme:

Can we get around the problem? Well, yes. Some children by the same parents are born when the parents are married and others later or before. One can also expand the definition of 'married' to include de facto civil marriage (long-term cohabitation). I am not aware of a such study, but it might exist, and it could be done using Nordic register data. However, does marriage have good causal effects in other ways? Here's two informative studies regarding crime:

Sampson, R. J., Laub, J. H., & Wimer, C. (2006). Does marriage reduce crime? A counterfactual approach to within‐individual causal effects. Criminology, 44(3), 465-508.

Although marriage is associated with a plethora of adult outcomes, its causal status remains controversial in the absence of experimental evidence. We address this problem by introducing a counterfactual life-course approach that applies inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) to yearly longitudinal data on marriage, crime, and shared covariates in a sample of 500 high-risk boys followed prospectively from adolescence to age 32. The data consist of criminal histories and death records for all 500 men plus personal interviews, using a life-history calendar, with a stratified subsample of 52 men followed to age 70. These data are linked to an extensive battery of individual and family background measures gathered from childhood to age 17 — before entry into marriage. Applying IPTW to multiple specifications that also incorporate extensive time-varying covariates in adulthood, being married is associated with an average reduction of approximately 35 percent in the odds of crime compared to nonmarried states for the same man. These results are robust, supporting the inference that states of marriage causally inhibit crime over the life course.

This study is tiny so not of much interest except for the method and idea. Here's a large-scale replication:

Airaksinen, J., Aaltonen, M., Tarkiainen, L., Martikainen, P., & Latvala, A. (2023). Associations between cohabitation, marriage, and suspected crime: A longitudinal within-individual study. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 9(1), 54-70.

The effects of marriage on criminal behavior have been studied extensively. As marriages today are typically preceded by cohabiting relationships, there is a growing need to clarify how different relationship types are associated with criminality, and how these effects may be modified by relationship duration, partner’s criminality, and crime type. We used Finnish longitudinal register data and between- and within-individual analyses to examine how cohabitation and marriage were associated with suspected crime. The data included 638,118 residents of Finland aged 0–14 in 2000 and followed for 17 years for a suspected crime: having been suspected of violent, drug, or any crime. Between-individual analyses suggested that those who were cohabiting or married had a 40–65% lower risk of being suspected of a crime compared to those who were single, depending on the type of crime. The within-individual analysis showed a 25–50% lower risk for suspected crime when people were cohabiting or married compared to time periods when they were single. Those in a relationship with a criminal partner had 11 times higher risk for suspected crime than those in a relationship with a non-criminal partner. Forming a cohabiting relationship with a non-criminal partner was associated with reduced criminality. The risk reduction was not fully explained by selection effects due to between-individual differences. Marriage did not introduce further reduction to criminality. Our findings demonstrate that selection effects partly explain the association between relationship status and criminality but are also compatible with a causal effect of cohabitation on reduced risk of being suspected of a crime.

The estimates are imprecise, of course, due to the relatively few datapoints most men contribute. But we can clearly see that the periods of a man's life where he is married, he commits fewer crimes as determined by the Finnish justice system. The same finding held for women too.

While it is possible there are confounders at play here, they cannot be genetic or otherwise constant across a person's life. One would have to posit changes in people's personalities that plausibly cause both and are large enough to matter in this case. Perhaps some people got addicted to drugs, got divorced and eventually was convicted of a drug related crime. These studies cannot rule out such scenarios, but they are a great start. A Swedish study found that men who had committed a crime, and then married had a lower chance of committing another crime ... unless their spouse was a criminal too, in which case it was higher. This fits with a causal role of spouses in regulating behavior, and the differential effect of the spouse finding was also replicated in the Netherlands.

If we accept the causal role of marriage in reducing crime, or stable relationships in general, we would make a prediction that the historical decline in relationships should lead to an increase in crime. However, in general, we find that there is a decline in crime in most places if we ignore immigrants and sometimes even if we do not. While we could infer from this that marriage is not really a protective causal factor, I think a wiser conclusion would be that there are other crime-reducing causes that are much stronger than the decline of marriage's crime-causing effect. An obvious factor is that the population is getting older and young men commit most crimes, so population aging causes a large decline in crime.

"There is a stark decrease in 'out of wedlock' (outside marriage) births, especially in Blacks."

Please correct to "stark increase." (I would also write: "There has been ...").

This resonates with my lived experience in that I haven't used any illegal drugs since I met my wife, because I feel like she would be disappointed in me if I did, whereas previously I would invariably partake when offered.