The dimensionality of politics

It's a big mess

Most political science research is based on a 1 dimensional model of politics: left vs. right. However, this model is actually and obviously false in a nontrivial way. Take studies like:

Feldman, S., & Johnston, C. (2014). Understanding the determinants of political ideology: Implications of structural complexity. Political Psychology, 35(3), 337-358.

There has been a substantial increase in research on the determinants and consequences of political ideology among political scientists and social psychologists. In psychology, researchers have examined the effects of personality and motivational factors on ideological orientations as well as differences in moral reasoning and brain functioning between liberals and conservatives. In political science, studies have investigated possible genetic influences on ideology as well as the role of personality factors. Virtually all of this research begins with the assumption that it is possible to understand the determinants and consequences of ideology via a unidimensional conceptualization. We argue that a unidimensional model of ideology provides an incomplete basis for the study of political ideology. We show that two dimensions—economic and social ideology—are the minimum needed to account for domestic policy preferences. More importantly, we demonstrate that the determinants of these two ideological dimensions are vastly different across a wide range of variables. Focusing on a single ideological dimension obscures these differences and, in some cases, makes it difficult to observe important determinants of ideology. We also show that this multidimensionality leads to a significant amount of heterogeneity in the structure of ideology that must be modeled to fully understand the structure and determinants of political attitudes.

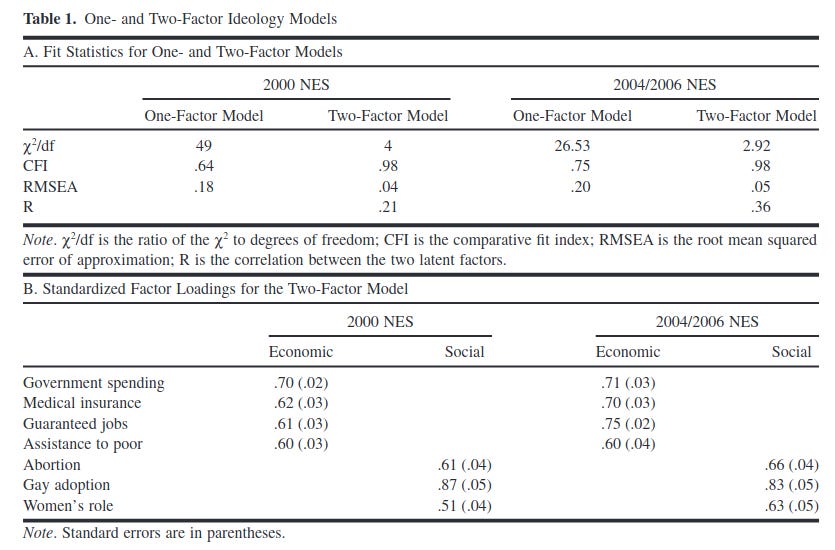

The idea is simple enough. You give people a bunch of policy questions, have them rate them by agreement, and then factor analyze the results. Do you get a nice big first factor? Not really:

By literally any standards of model fit, the 1 factor model fails horribly, but the 2 factor one does alright. The results didn't differ by year of the survey (this is the ANES dataset, which you can download too).

They furthermore show that relationships of policies in the 2 dimensional model are very different and stronger than those in the 1 dimensional model:

Versus 1 dimensional model:

Note the differences in the model fits, by R2. In particular, the second dimension of social values is a lot easier to predict when its disentangled from the economics policy variance. But it gets worse. This problem is more severe for analyzing people who don't know a lot about politics:

In factor, this is really a strong moderator in the factor analysis:

High vs. low informed voters here refer to the number of political knowledge questions a given person got right, then split by the median:

Now we have a set of questions concerning various public figures. We want to see how much information about them gets out to the public from television, newspapers and the like. The first name is TRENT LOTT. What job or political office does he NOW hold?

WILLIAM REHNQUIST?

TONY BLAIR?

JANET RENO?

What U.S. state does George W. Bush live in now?

What U.S. state is Al Gore from originally?

What U.S. state does Dick Cheney live in now?

The authors conclude:

Our demonstration that political ideology is at least two dimensional is not new. There is a considerable amount of theory and prior research that supports this position. However, too much recent work on the determinants of ideology has failed to fully appreciate the consequences of multidimensionality. We have shown that modeling the predictors of ideology yields substantially different conclusions in a two-dimensional model than the one-dimensional model. Demographic correlates of ideology that are clear and differentiated in the two-dimensional model are generally obscured in the one-dimensional model. Perhaps more importantly, psychological variables that have been used to describe the differences between liberals and conservatives have very different effects on economic and social ideology. In particular, authoritarianism and religiosity have substantively large effects on social conservatism but no significant effect on economic conservatism. This pattern is observed equally for those high and low in political sophistication. It simply is not accurate to conclude that authoritarian characteristics necessarily lead to opposition to equality. Those high on authoritarianism are very likely to be socially conservative, but they are just as likely to be liberal on economic policy as conservative. The results of the latent class model showed one group of people (Latent Class 2) for whom high levels of authoritarianism coexist with very liberal economic policy positions.

The final part is particularly apt these days.

That kind of study is not the only such study, here's some more:

Swedlow, B. (2008). Beyond liberal and conservative: Two-dimensional conceptions of ideology and the structure of political attitudes and values. Journal of Political Ideologies, 13(2), 157-180.

This article analyzes conceptual similarities and differences in selected prior work on ideological multi-dimensionality and finds substantial conceptual convergence accompanied by some provocative divergence. The article also finds that evidence from a recent survey of the American public largely validates areas of conceptual convergence. Respondents' political attitudes vary in two dimensions that are associated with different value structures—specifically, with different rankings of liberty, order, and ‘caring for those who need help’. As a result, liberals, conservatives, and libertarians are identified more fully than previously possible. But the evidence does not allow the validation of one conception over another in the area where they diverge most markedly. Does the fourth ideological type value order and equality, making them ‘communitarians’, or are these respondents better understood as a humanitarian, paternalistic, hierarchical subtype, the ‘inclusive social hierarch’, since they value order as well as ‘caring for those who need help’?

Carmines, E. G., Ensley, M. J., & Wagner, M. W. (2012, October). Political ideology in American politics: one, two, or none?. In The Forum (Vol. 10, No. 3). De Gruyter.

Are Americans ideological, and if so, what are the foundations of their ideology? According to Converse’s seminal view, whatever the case in other western democracies and despite its centrality to traditional versions of textbook democracy, the American public is distinctly non-ideological. Our objective is to compare the standard and by far most widely used measure of political ideology—a measure that presumes ideology is one-dimensional—to a more recent measure that allows for a multi-dimensional conception and measurement. This measure demonstrates that while American political elites compete across a single dimension of conflict, the American people organize their policy attitudes around two distinct dimensions, one economic and one social. After explaining how we derived the measure and how it can be used to develop five separate ideological groups, we show how these groups differ politically and why it is not possible to map their preferences onto a one-dimensional measure of ideology.

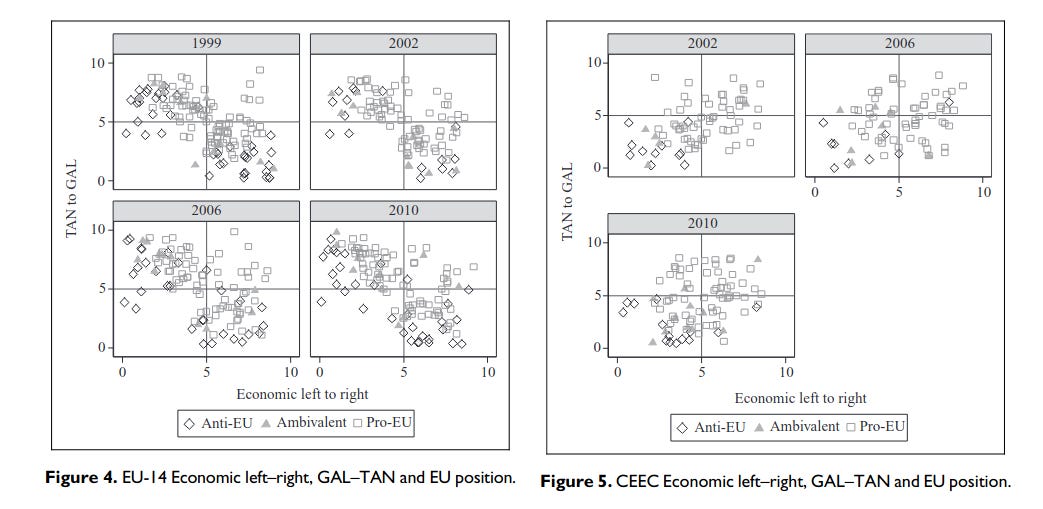

Prosser, C. (2016). Dimensionality, ideology and party positions towards European integration. West European Politics, 39(4), 731-754.

The rise of political contestation over European integration has led many scholars to examine the role that broader ideological positions play in structuring party attitudes towards European integration. This article extends the existing approaches in two important ways. First, it shows that whether the dimensionality of politics is imagined in a one-dimensional ‘general left‒right’ form or a two-dimensional ‘economic left‒right/social liberal-conservative’ form leads to very different understandings of the way ideology has structured attitudes towards European integration, with the two-dimensional approach offering greater explanatory power. Second, existing approaches have modelled the influence of ideology on attitudes towards European integration as a static process. This article shows that the relationship between ideology and European integration has changed substantially over the history of European integration: divisions over social issues have replaced economic concerns as the main driver of party attitudes towards European integration.

It gets worse still. This one big dimension of political ideology isn't even internally consistent across countries:

Wojcik, A. D., Cislak, A., & Schmidt, P. (2021). ‘The left is right’: Left and right political orientation across Eastern and Western Europe. The Social Science Journal, 1-17.

Left-right political auto-identification has been used widely in socio-political research to interpret and organize political attitudes and opinions. In this paper we analyse whether the meaning of left-right orientation is the same in Eastern Europe and Western Europe. Using data from two big European survey programmes, European Social Survey and European Values Study, we show that while citizens’ support for economic liberalism is positively related to their left-right political auto-identification, their support for cultural liberalism is negatively related. More importantly, we also present evidence for the regional diversity hypothesis, which shows that this pattern was more prominent among citizens of Western European countries those of Eastern European countries. The results confirm the specificity of Eastern Europe when it comes to relationships between political auto-identification and other beliefs that are traditionally linked, implying that the concept of left-right political auto-identification cannot be transferred mechanically between Eastern Europe and Western Europe.

So in the typical WEIRD countries, self-rated left-right position correlates positively with economic liberalism, i.e., free market support. But there's a bunch of countries where the association is about zero or slightly negative. Sometimes the results are really mysterious, such as the contrast between Czech Republic (strong positive cor.) vs. Poland (weak negative cor.) even though these are neighbors with mostly shared histories, and closely related cultures, languages and genetics!

One weird study perhaps? No, there's replications:

Malka, A., Soto, C. J., Inzlicht, M., & Lelkes, Y. (2014). Do needs for security and certainty predict cultural and economic conservatism? A cross-national analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(6), 1031–1051. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036170

We examine whether individual differences in needs for security and certainty predict conservative (vs. liberal) position on both cultural and economic political issues and whether these effects are conditional on nation-level characteristics and individual-level political engagement. Analyses with cross-national data from 51 nations reveal that valuing conformity, security, and tradition over self-direction and stimulation (a) predicts ideological self-placement on the political right, but only among people high in political engagement and within relatively developed nations, ideologically constrained nations, and non-Eastern European nations, (b) reliably predicts right-wing cultural attitudes and does so more strongly within developed and ideologically constrained nations, and (c) on average predicts left-wing economic attitudes but does so more weakly among people high in political engagement, within ideologically constrained nations, and within non-Eastern European nations. These findings challenge the prevailing view that needs for security and certainty organically yield a broad right-wing ideology and that exposure to political discourse better equips people to select the broad ideology that is most need satisfying. Rather, these findings suggest that needs for security and certainty generally yield culturally conservative but economically left-wing preferences and that exposure to political discourse generally weakens the latter relation. We consider implications for the interactive influence of personality characteristics and social context on political attitudes and discuss the importance of assessing multiple attitude domains, assessing political engagement, and considering national characteristics when studying the psychological origins of political attitudes.

NSC is need for security and certainty. In American political psychology, this has generally been considered a right-wing/conservative thing, and there's endless papers talking in smug terms about the paranoid conservatives (read anything by John Jost). The table shows that this association depends on the country, which they grouped by human development, or simply by being East Europe or not.

What about protests? Those are surely a left-wing thing, right? Right-wingers play by the rules, left-wingers are street people. Yes, in some places:

Borbáth, E., & Gessler, T. (2020). Different worlds of contention? Protest in northwestern, southern and eastern Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 59(4), 910-935.

Despite the voluminous literature on the ‘normalisation of protest’, the protest arena is seen as a bastion of left-wing mobilisation. While citizens on the left readily turn to the streets, citizens on the right only settle for it as a ‘second best option’. However, most studies are based on aggregated cross-national comparisons or only include Northwestern Europe. We contend the aggregate-level perspective hides different dynamics of protest across Europe. Based on individual-level data from the European Social Survey (2002–2016), we investigate the relationship between ideology and protest as a key component of the normalisation of protest. Using hierarchical logistic regression models, we show that while protest is becoming more common, citizens with different ideological views are not equal in their protest participation across the three European regions. Instead of a general left predominance, we find that in Eastern European countries, right-wing citizens are more likely to protest than those on the left. In Northwestern and Southern European countries, we find the reverse relationship, left-wing citizens are more likely to protest than their right-wing counterparts. Lessons drawn from the protest experience in Northwestern Europe characterised by historical mobilisation by the New Left are of limited use for explaining the ideological composition of protest in the Southern and Eastern European countries. We identify historical and contemporary regime access as the mechanism underlying regional patterns: citizens with ideological views that were historically in opposition are more likely to protest. In terms of contemporary regime access, we find that partisanship enhances the effect of ideology, while ideological distance from the government has a different effect in the three regions. As protest gains in importance as a form of participation, the paper contributes to our understanding of regional divergence in the extent to which citizens with varying ideological views use this tool.

The differences are completely stable across the years 2002-2016 in northwest Europe, are increasing in south Europe, and are only barely coming into existence in East Europe.

That's voters. What about political parties? I got you.

Bakker, R., De Vries, C., Edwards, E., Hooghe, L., Jolly, S., Marks, G., ... & Vachudova, M. A. (2015). Measuring party positions in Europe: The Chapel Hill expert survey trend file, 1999–2010. Party Politics, 21(1), 143-152.

Somewhat bizarre labeling, but GAL-TAN means "green/alternative/libertarian (GAL) to traditional/authoritarian/nationalist (TAN) dimension". Again, we see that in central and east Europe (CEEC), the results are reversed, with the more free market parties being less into Woke stuff and more pro-EU.

OK, but is this just a East European thing? No.

Pan, J., & Xu, Y. (2018). China’s ideological spectrum. The Journal of Politics, 80(1), 254-273.

The study of ideology in authoritarian regimes—of how public preferences are configured and constrained—has received relatively little scholarly attention. Using data from a large-scale online survey, we study ideology in China. We find that public preferences are weakly constrained, and the configuration of preferences is multidimensional, but the latent traits of these dimensions are highly correlated. Those who prefer authoritarian rule are more likely to support nationalism, state intervention in the economy, and traditional social values; those who prefer democratic institutions and values are more likely to support market reforms but less likely to be nationalistic and less likely to support traditional social values. This latter set of preferences appears more in provinces with higher levels of development and among wealthier and better-educated respondents. These findings suggest that preferences are not simply split along a proregime or antiregime cleavage and indicate a possible link between China’s economic reform and ideology.

So China is similarly 'reversed' to the West. So maybe it's not East Europe or China that's WEIRD, but us. Alternatively, it has to do with being ex-communist or not. I didn't see any data from the rest of Asia, but using The World Value survey (also public), this should be easy enough to find out. Exercise left to the reader.

Conclusions

Political ideology cannot generally be reduced to 1 dimension without massive loss of information and probably substantial chance of misinterpretation.

Political ideology doesn't even work the same way, as in, have the same structure across countries.

Correlates of political ideology don't work the same way across countries either, such as fondness of protesting.

Political knowledge influences ideology structure so that it becomes more 1 dimensional. This is why political partisans, who know a lot about politics, tend to be so, well, one dimensional in their thinking. That's because they are.

This also suggests that studying people who defy this trend might be very interesting. That's the radical center or resolute center, higher political knowledge yet not so 1 dimensional.

Trying to predict the politics of people who are not interested in it will be mostly futile as their policy preferences are highly random (low correlations to each other).

Theories of political action and actors based on a 1 dimensional model are somewhat suspect.

Bonus: Twins! Genetics!

So if political ideology becomes more consistent with more political knowledge, does that then also mean that such people show higher heritabilities? After all, these are based on the strength of the correlations, right? The answer is yes:

Kalmoe, N. P., & Johnson, M. (2022). Genes, ideology, and sophistication. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 9(2), 255-266.

Twin studies function as natural experiments that reveal political ideology’s substantial genetic roots, but how does that comport with research showing a largely nonideological public? This study integrates two important literatures and tests whether political sophistication – itself heritable – provides an “enriched environment” for genetic predispositions to actualize in political attitudes. Estimates from the Minnesota Twin Study show that sociopolitical conservatism is extraordinarily heritable (74%) for the most informed fifth of the public – much more so than population-level results (57%) – but with much lower heritability (29%) for the public’s bottom half. This heterogeneity is clearest in the Wilson–Patterson (W-P) index, with similar patterns for individual index items, an ideological constraint measure, and ideological identification. The results resolve tensions between two key fields by showing that political knowledge facilitates the expression of genetic predispositions in mass politics.

So in twin parties where both twins know a lot about politics, the heritability went up to 74%, compared to 32% in those with low knowledge. In fact, in those, C was really strong at 27%. Basically these are the normies who don't care and just adopt the political values of their parents.

Bonus: But you did it too!

Yep, more than once too. My defense? I knew it was a simplification, but in order to talk about the thing everybody else is talking about, it was practical. I imagine the other researchers are using a similar defense. But also sometimes I didn't such as in this 2015 study. Sometimes a given dataset doesn't have the right questions. I don't think we could have done our Mormon eugenics study using a 2-dimensional model because the questions aren't available for all the years. I am not sure if they are available for the study of politics and mental illness, but perhaps. You should look (yes, you). Those data are public too (GSS). I will also continue to have to use a simplified wrong approach because otherwise reviewers will complain a lot. Mea culpa.

The meme of the two-dimensional scatterplot, with social liberty along one axis and economic liberty along another axis, has been around for a long time, maybe twenty years or more. Lately I dismissed it because I believed it to be unscientific and because I believed that two dimensions is not enough to capture political variation, but now I know it was at the forefront of scientific progress! I expect that the one-dimensional model is often preferred by political scientists mainly because you can fit any hypothesis you like onto it. The two-dimensional model has restrictive adherence to reality.

I find that there is confusion here between political idealogy and policy spectrum. Politics is always going to depend on the personalities who are involved and consequently this kind of idealogy is expressed in an over-sufficient personal a way and with an insufficient logical basis, so that it is not suitable for any intellectually honest analysis. What we want firstly is proper definitions of these various kinds of idealogies that are free from political motivations and bias, and then we would be in a better state to analyse them. I am not pretending that such definitions are easy to formulate, but otherwise we are in danger of each createing in his/her own (and differing) mind's eye, a variety of ideas of what it is all about.