The genetics of beliefs

Not a doomer

Nathan Cofnas wrote a great piece the other day, Beating Woke with Facts and Logic, which included this part:

Beliefs Aren’t Genetically Determined

Should we execute murderers? Raise taxes on the rich? Believe in God? How you answer these questions can be predicted with unsettling accuracy based on your genes. Some people draw the conclusion that beliefs are therefore genetically determined and there’s nothing we can do to change them. You can’t argue someone out of being woke any more than you can argue someone out of having blue eyes or sickle cell anemia. But this is a mistake.

High hereditability does not mean genetically determined. Heritability is relative to a population and an environment: within a particular environment, the heritability of a trait in a population is the proportion of the variance associated with genetic differences. If you change the environment, the genes “for” X might lead to Y. Genes that “coded for” girls being a tomboy in the 1990s now code for cutting their breasts off and getting hormone therapy. Genes “for” hanging witches in Salem in the 1690s drove social media mobs in the 2010s. In an informational environment where facts about hereditarianism are readily accessible from credible sources, genes that now lead to wokism might have a different effect.

The debate is the usual one about how to defeat the current version of egalitarianism (wokeness) for good. Should one use facts and logic, or institutional power? Chris Rufo is quoted as saying (from an X exchange with Cofnas):

The crux of Cofnas’s argument is that abstract argument and scientific rationality govern, or, at least, should govern, the world. This is as much of a fantasy as the blank slate thesis. “Win the battle of ideas” is the political equivalent of “show them you have the best Pokémon cards”—while your enemies show up with tanks. Politics is not a debating society; institutions do not survive on facts and logic alone....[T]he implicit logic is something like this: brave truth-tellers will show existing elites a series of race and IQ graphs, and then, poof!, the institutions will suddenly self-dismantle and adopt new ideologies wholesale; departments of critical race theory will acknowledge the extraordinary prowess of their arguments and resign en masse.

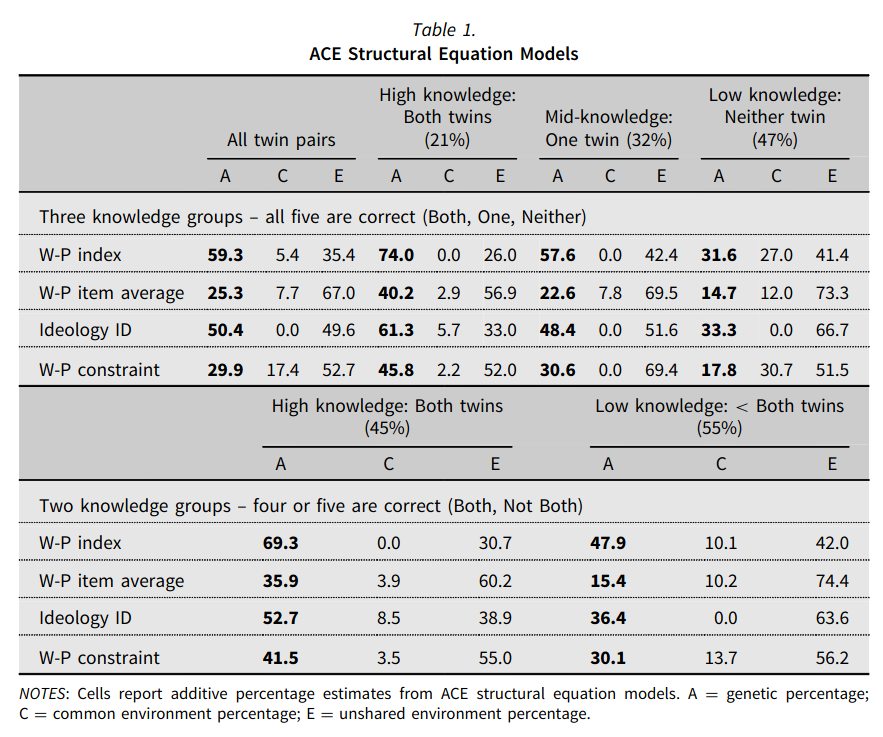

Both are right in their respective emphasis. In this post I want to dig into the genetics of particular beliefs or aggregate dimensions of belief such as conservatism. We can apply the usual family designs to estimate the heritability of various kinds of beliefs. This can be done for the specific beliefs or broader tendencies among beliefs, which we call latent dimensions, factors (of the mind), or ideologies depending on context. Using twins, we can estimate the heritability of these political dimensions of belief like this:

The thing to note here is that the heritability of beliefs seemingly also depends on which twins you study. Those twins low in political knowledge show lower heritabilities and higher unshared environment (’everything else’ being a better name). Since this latter component includes noise, that is, essentially random responding, the obvious interpretation here is that people who don’t know much about politics fill out opinion questionnaires somewhat at random. This makes the dimensions less clear for such subjects, and the proportion of true variance (non-error) in the scores will be lower. The effect of more random error is always to make findings weaker, and this is also true for heritabilities. Since measurement error is always present, heritabilities are almost always under-estimated.

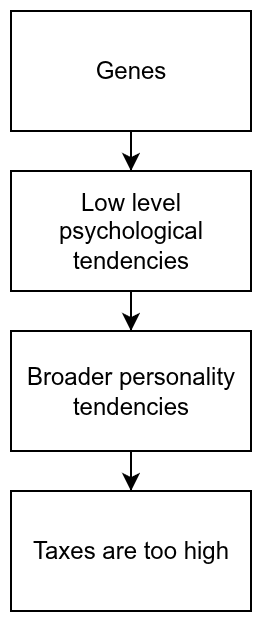

To the above, we should note that beliefs aren’t really genetically encoded. So when we say that political beliefs or dimensions are heritable, the causal chain is rather long from the gene to the belief. We can sketch it as something like this:

We begin with an extraordinarily large amount of genetic variation. You have TT at some locus, but I have AT, and our friend has AA. Repeat this but at 10+ million places in the genome. The effects may add up to some behavioral differences. I called these low level psychological tendencies, which may be smell sensitivity, social conformity, activity level, or whatever. These are often called facets of personality, which are usually considered the sub-components of dimensions like the Big 5 (OCEAN). If you don’t like OCEAN, then substitute HEXACO, alternative Big 5, 16PF, or whatever system you prefer. These dimensions can also be aggregated to some extent due to various intercorrelations, and in the end one gets Big 5, Big 2, and Big 1 (GFP). In the simplified model, these then cause variation in political beliefs. Perhaps you have a high activity level and enjoy working, but you see others are apparently sitting in their sofas all day, so you start getting annoying you have to pay taxes to support their laziness. Next step you start believing that the taxes are too high. As such, a belief that taxes are too high wasn’t encoded in your genes, but personality tendencies, that in the current social context leads to that belief, were encoded to some extent.

This is how, roughly, many people conceive of the heritability of beliefs beliefs. They are 1) based on lower-level pre-existing tendencies, and 2) they are context dependent, that is, result from interactions in the statistical sense. The first part about the intermediate cause is important too. Children don’t have much in terms of political beliefs (aside from ‘give me what I want-ism’, tendencies towards fairness vs. greed etc.), but they do have obvious personality variation. The study of political psychology can also largely be viewed as the attempt to find these causes of political beliefs, and especially so if they are unfavorable to the Out Group (’rightists are dumb, leftists are crazy’ is the current battleground in the Western world, both are true to some extent).

There is a study that tried to test the personality > politics causal model using a genetically sensitive design:

Verhulst, B., Eaves, L. J., & Hatemi, P. K. (2012). Correlation not causation: The relationship between personality traits and political ideologies. American journal of political science, 56(1), 34-51.

The assumption in the personality and politics literature is that a person’s personality motivates them to develop certain political attitudes later in life. This assumption is founded on the simple correlation between the two constructs and the observation that personality traits are genetically influenced and develop in infancy, whereas political preferences develop later in life. Work in psychology, behavioral genetics, and recently political science, however, has demonstrated that political preferences also develop in childhood and are equally influenced by genetic factors. These findings cast doubt on the assumed causal relationship between personality and politics. Here we test the causal relationship between personality traits and political attitudes using a direction of causation structural model on a genetically informative sample. The results suggest that personality traits do not cause people to develop political attitudes; rather, the correlation between the two is a function of an innate common underlying genetic factor.

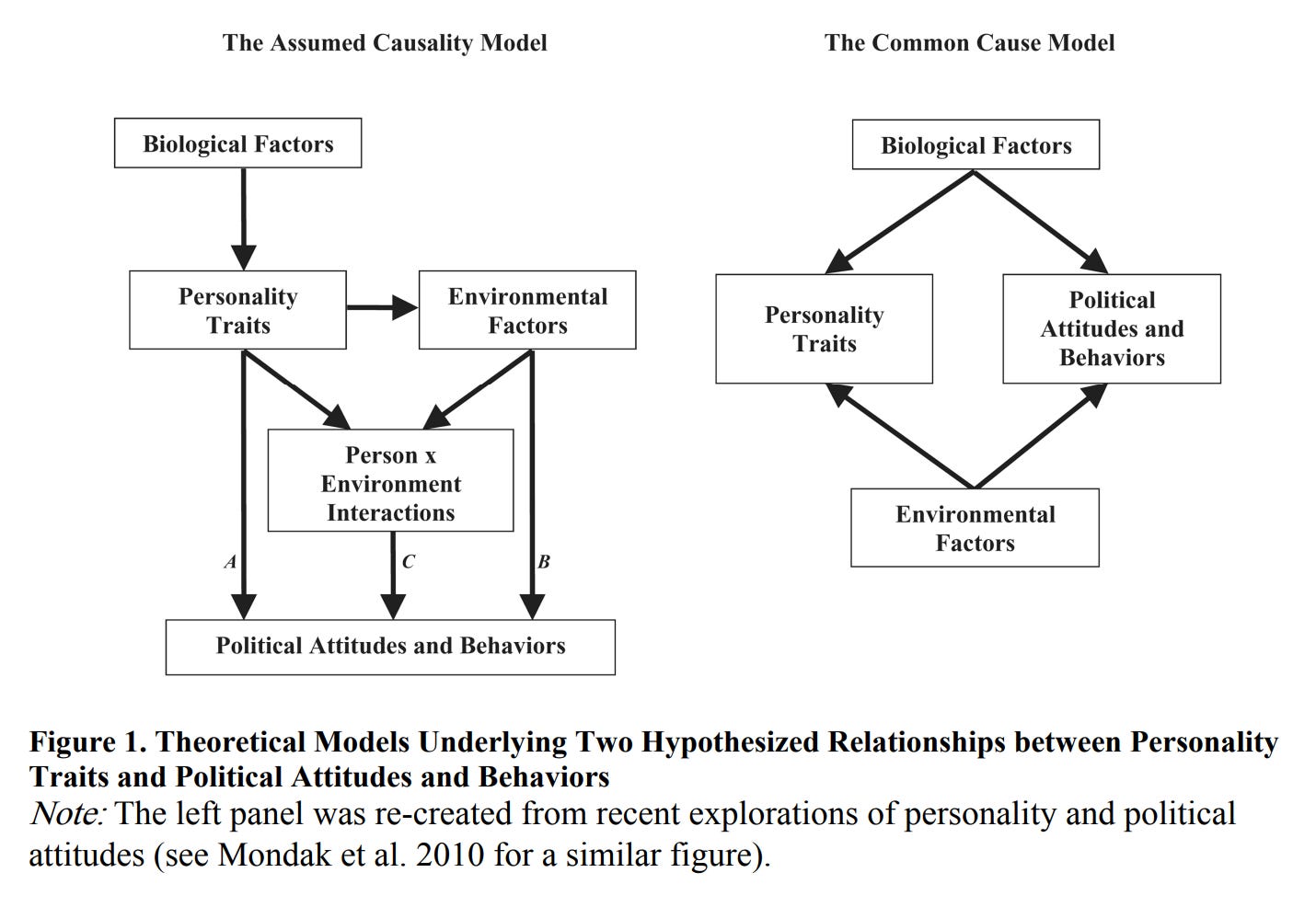

They provide these two DAG models:

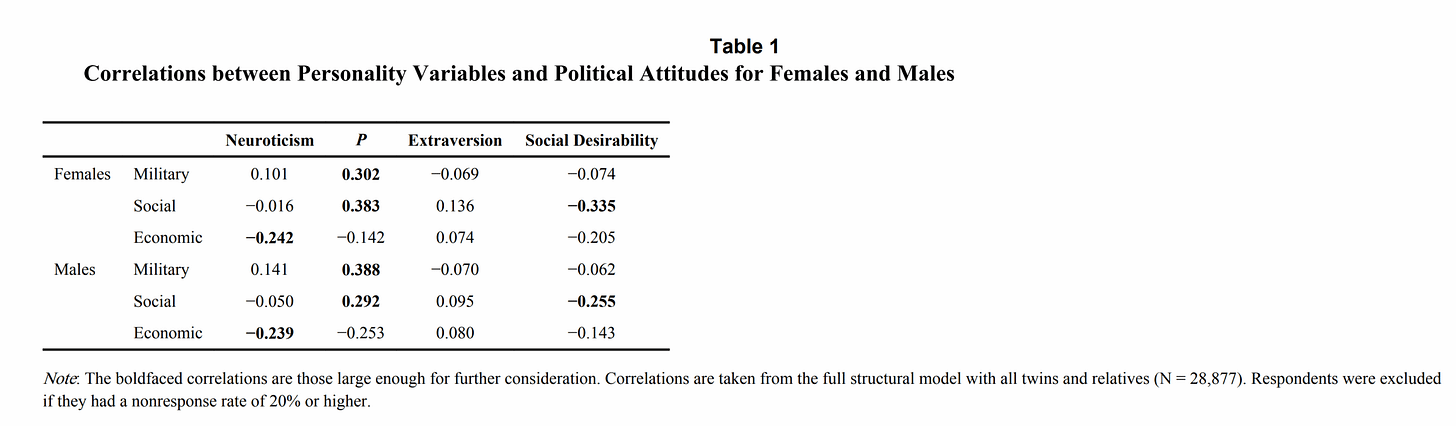

They had some thousands of twin pairs (MZ+DZ) and used the classical twin design. Their measures of personality and ideology are outdated and include the following:

The values are coded in the right-wing direction. Thus, neuroticism (Eysenck model) correlate moderately with leftist economic views (0.24), but slightly positively with rightist military views (0.12). The psychoticism factor shows the strongest correlations which is unfortunate because it is hard to interpret. The authors note:

Eysenck’s Psychoticism measure was poorly labeled. Hence, going forward, we use the less pejorative, abbreviated label P, which was also adopted by Eysenck. Having a high Psychoticism score is not a diagnosis of being clinically psychotic or psychopathic. Rather, P is positively correlated with tough-mindedness, risk-taking, sensation-seeking, impulsivity, and authoritarianism (Adorno et al. 1950; Altemeyer 1996; Eysenck and Eysenck 1985, McCourt et al. 1999). In social situations, those who score high on P are more uncooperative, hostile, troublesome, and socially withdrawn, but lack feelings of inferiority and have an absence of anxiety. At the extremes, those scoring high on P are manipulative, tough-minded, and practical (Eysenck 1954). By contrast, people low on P are more likely to be more altruistic, well socialized, empathic, and conventional (Eysenck and Eysenck 1985; Howarth 1986). As such, we expect higher P scores to be related to more conservative political attitudes, particularly for militarism and social conservatism.

Eysenck’s P has a complex relationship to the FFM. Specifically, the Openness to Experience dimension, which has received the majority of the attention within personality and politics studies, is not well captured by Eysenck’s taxonomy (McCrae 1987; McCrae and Costa 1985). While P predicts conservative political attitudes in a similar manner as Openness predicts liberal political attitudes (Eysenck 1954; McCrae 1995), and limited evidence finds P moderately negatively correlated with the greater Openness to Experience dimension (Eysenck and Eysenck 1985; Larstone et al. 2002), P also correlates positively with certain subfacets of Openness, such as creativity and originality (Eysenck and Eysenck 1985; Rawlings et al. 1998). Furthermore, P is negatively correlated with Conscientiousness (McCrae and Costa 1985; Zuckerman et al. 1993), even though both traits correlate positively with political conservatism (Carney et al. 2008; Verhulst, Hatemi, and Martin 2010). The remaining relationship, P being negatively correlated to Agreeableness, is perhaps the least complex, as measures of Agreeableness are part of the measure of P with regard to tough-mindedness and being uncooperative.

The choice of P is also unfortunate since that now overlaps with general psychopathology, also called p/P. Maybe modern psychologists should re-adopt the hard science approach and go back to using Greek letters (e.g. Cronbach’s alpha, McDonald’s omega). Perplexity tells me to use Ψ (psi), which sort of fits since general psychopathology is usually seen as a hierarchical trait based on 3-ish main sub-dimensions (internalizing, externalizing and ‘others’).

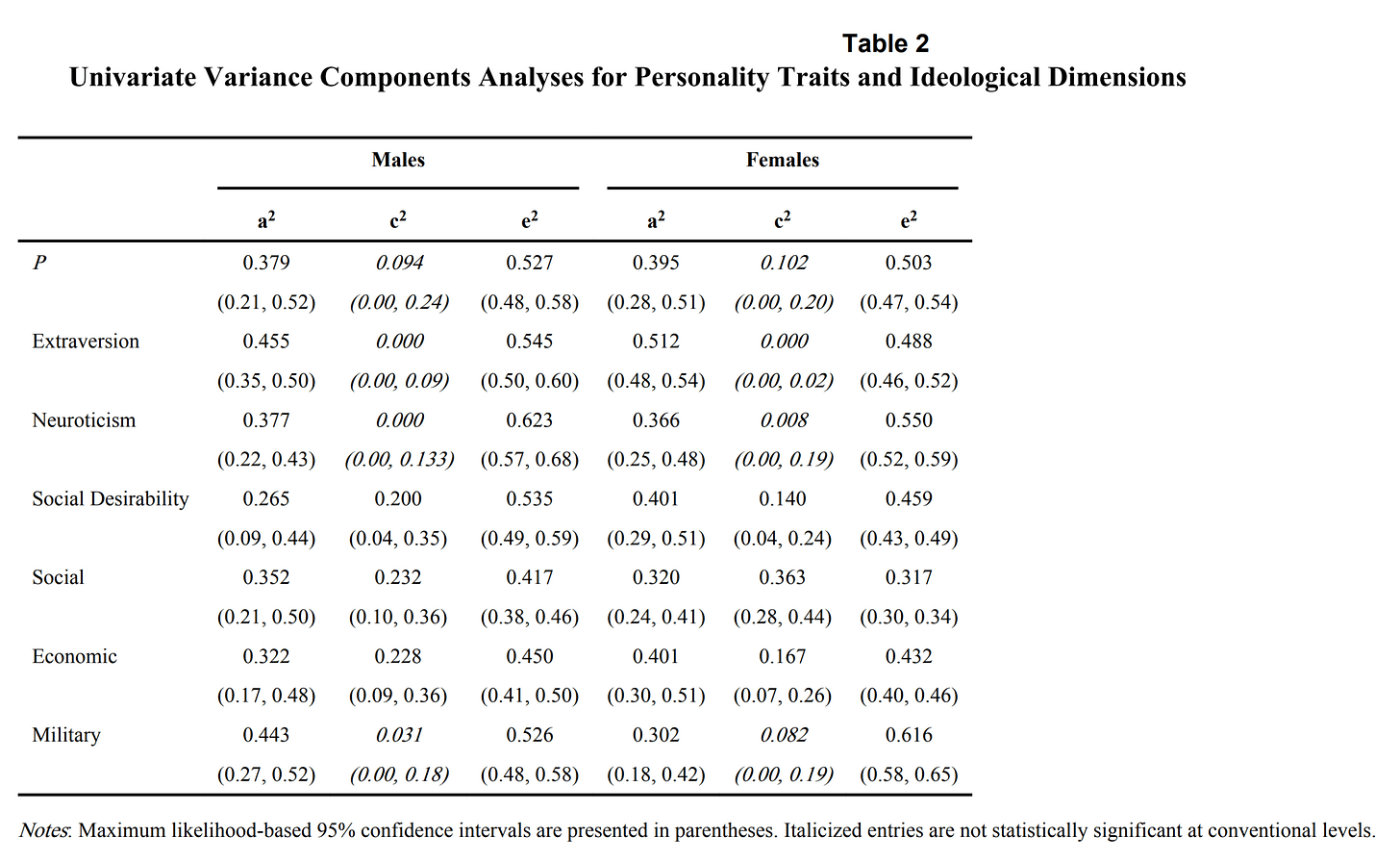

Language aside, we aren’t too surprised to see that tough-minded people are more right-wing on military and social matters, but curiously also slightly left-wing on economics (maybe they want to be tough on the capitalists too). Note that the political questions were from the Wilson-Patterson (1968) measure, and the data were collected in the 1980s. By modern standards, the questions are thus quite outdated. The authors find that all of their measures show moderate heritability:

I don’t know why they split them by sex, as their study is clearly underpowered to find differences. I think they used observed scores (from CFA), so the measurement errors will make the values for A and C too low, and those for E too high. Nevertheless, the mean heritability is about 38%, family environment 12% and the rest 50%.

Next up, they first employ Cholesky decomposition to see to which extent the traits overlap genetically. They find that they do to some substantial extent. However, finding that, say, psychoticism and RW military views overlap genetically doesn’t tell you which causes which, or whether they just have a common genetic cause (perhaps some lower level personality constructs). Thus, they move on to the more powerful, in theory, approach:

To determine which causal direction best fits the data, the DoC model leverages the genetic relatedness of individuals within the same family to parse the causal structure between personality traits and political attitudes by utilizing the cross-twin cross-trait covariance to determine the causal direction.5 Mathematically, the DoC model compares the cross-twin cross-trait covariance with the two products of the cross-twin withintrait covariance with the within-person cross-trait. If the pattern of cross-twin cross-trait covariance mimics the product of cross-twin personality covariance and the within-person personality and attitudes covariance, then the best-fitting model will suggest that personality causes people to develop their political attitudes. If the cross-twin cross-trait covariance corresponds with the product of cross-twin attitudes covariance and the within-person personality and attitudes covariance, then the best-fitting model will suggest that attitudes cause people to develop their personality. If both products correspond with the cross-twin cross-trait covariance, causality cannot be determined, suggesting a correlation rather than causation (Heath et al. 1993). As such, the DoC model has the most power to detect causality when the pattern of phenotypic transmission is clearly distinct and becomes more difficult as the pattern of transmission becomes more similar.

I think it works roughly like this: Pick one twin and a trait (e.g. P), then compare non-P traits in the other twin and see how far they are moved in the expected direction of P (e.g. RW military views). Then reverse the traits and do it again. Do this for every combination and you should be able to see which cross-trait cross-twin correlations are the strongest. If any in particular stand out, this is the suggested causal path. They find that:

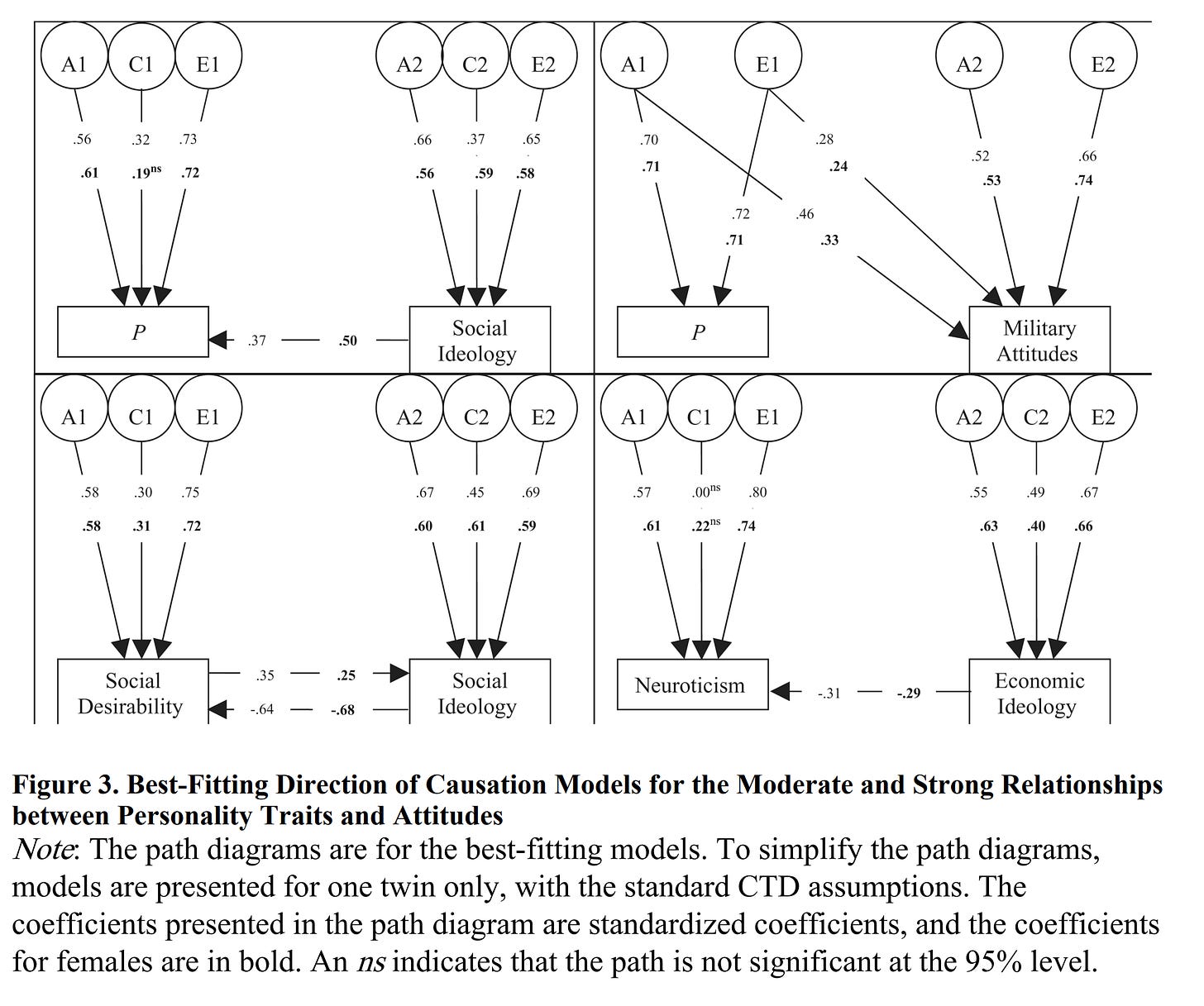

The determinations of causal direction is done using the usual model fitting horse race, which is what produced the above values (from the ‘best fitting models’). Thus, we see that they find seemingly impossible results:

Figure 3 presents the best-fitting DoC models for each of the relationships discussed above, with the complete model-fitting results presented in Table 3. As can be seen in Figure 3, the model that best captures the covariance structure of the data for both P and social ideology and Neuroticism and economic ideology is the reverse causation model where the political attitude causes the personality trait. Thus, in direct contrast with the existing assumption regarding the causal ordering of political attitudes and personality traits, across two completely independent analyses, the causal ordering appears to be the complete opposite of what is typically assumed.

The relationship between Social Desirability and social ideology is more complex. In this case, the best-fitting model is the reciprocal causation model with a negative feedback loop. Because the phenotypic correlation is negative, the product of the two pathways must also be negative, which is precisely what we find. Here, socially liberal attitudes causally result in more social desirability responses, as can be seen with the strong negative causal pathway. This strong negative causal effect is dampened by a weaker, though significant, positive causal effect flowing in the opposite direction.

The DoC analysis for the relationship between P and military attitudes supports a correlational, not causal, relationship. Specifically, because both constructs have an AE structure, the reciprocal causality DoC model and the Cholesky have the same degrees of freedom, and the DoC model is unable to accurately estimate a reciprocal causation model. In this case, both of the unidirectional models fit the data significantly worse than the Cholesky. Therefore, the model that most accurately fits the data is one with a common latent additive genetic factor accounting for the relationship between the two constructs. In other words, it is more plausible that the relationship between P and military attitudes is indicative of a common causal mechanism, or pleiotropy, rather than a sequential chain of causality.

Political views causes personality! Seems doubtful. There is also the question of differential measurement error which causes bias in this kind of analysis:

The final criticism of the current analyses is that all the traits we have utilized have some level of measurement error and if the errors in measurement are larger in one variable, the results may be biased (as is the case with measurement error in predictor variable in an ordinary least squares regression). In the DoC model, the causal pathway from the variable with more measurement error to the variable with less measurement error will be attenuated. We have attempted to minimize the impact of measurement error on our results by using confirmatory factor analysis to predict factor scores rather than constructing simple additive scales or individual items. Although the use of factor scores minimizes errors in measurement, it does not negate the problem of measurement error entirely.

I think another problem is that the personality constructs they used are too broad. As they themselves noted, psychoticism correlates with multiple Big 5 facets with opposite direction relationships to certain politics views. What then would be the causal effect of the broad construct? It is somewhat nonsensical to even think about.

The Verhulst study has 390 citations since 2012, so naturally I looked for any replications. There is one amusing longitudinal survey study supposedly showing that one can prime people into filling out their self-rated personality data a bit differently based on political primes. While the study has a large sample and some pre-registration, the p-values are like this:

... one-sided p = 0.08 ... one-sided p = 0.03 ... one-sided p = 0.03 ... one-sided p = 0.04 ... one-sided p = 0.04 ... one-sided p = 0.27 ... one-sided p = 0.08 ... one-sided p = 0.02 ... one-sided p = 0.002 ... one-sided p = 0.01 ... one-sided p = 0.05 ... one-sided p = 0.02

These are all the p values in their experimental section of the study.

This study also found shared genetic variation between social dominance trait and politics using twins. This study used cross-lagged longitudinal research to see if Big5 personality changes precede ideology changes, which they don’t. This twin study again confirmed genetic overlap between personality using the HEXACO this time. This extension of the original study by the same authors also find that personality changes don’t predict ideology changes, using the same data as above. That study is also the one that resulted in some controversy because they accidentally swapped the scales. The study really showed that liberals (in 1980s) were higher in psychoticism, the original phrasing was that conservatives were higher which the journalists then delightfully reported, until it was discovered and corrected (the journalists probably didn’t correct their articles though). Yet another twin study also confirmed the shared genetics using Swedish twins. This is my findings after skimming 6 pages of results of studies that cite the original one.

I want to return to the context sensitive nature of the findings. Much research in political dimensions have showed that the dimensions can change across time and place. The political axes are often partially flipped outside of the West, in particular in former communist East Europe. Insofar as there are some genes that cause preferences for capitalism (through whatever intermediate causes), and different genes that do the same for liberal social values. In, say, Germany, these genes would tend to point in opposite directions on left-right scale, but in East Europe, they would point in the same direction (anti-communist), at least until recently.

Or to put it another way. Some of these genes for being tough-minded and anti-authoritarian. They would tend to make you a communist if you lived in Nazi Germany, but a capitalist if you lived in communist DDR Germany, and a human rights advocate if you live in Pakistan. The effect of the personality trait on the political dimension will change depending on who is currently the Bad People in Charge. Any measure of overall heritability of political opinions, then, include the current direction of such personality variations, which may be different 20 years from now due to political realignments. As such, the genetic correlation between a political score for political conservatism in 1980 and one from 2020 should be relatively weak, as some of the sub-causes have changed directions or strength.

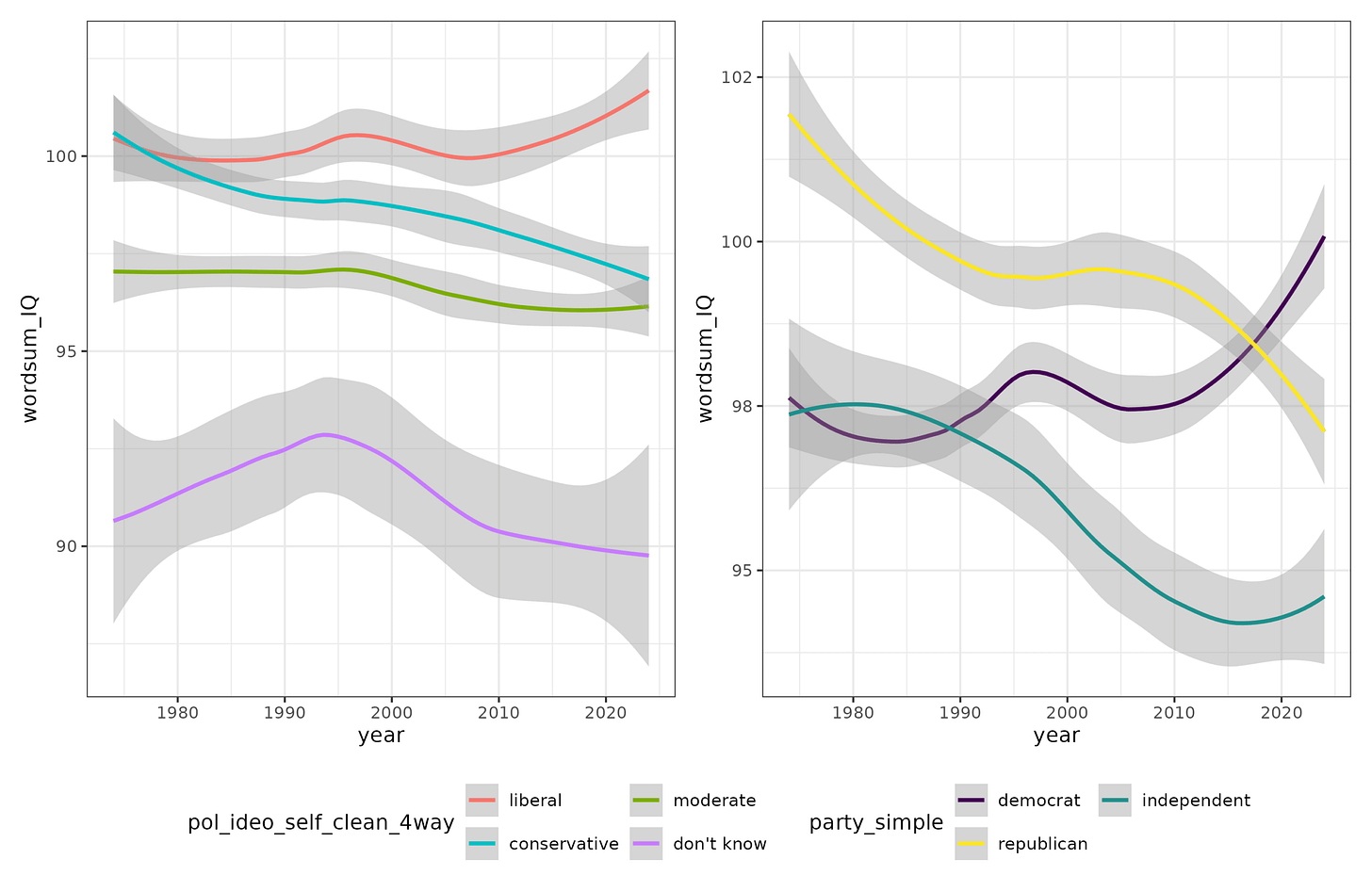

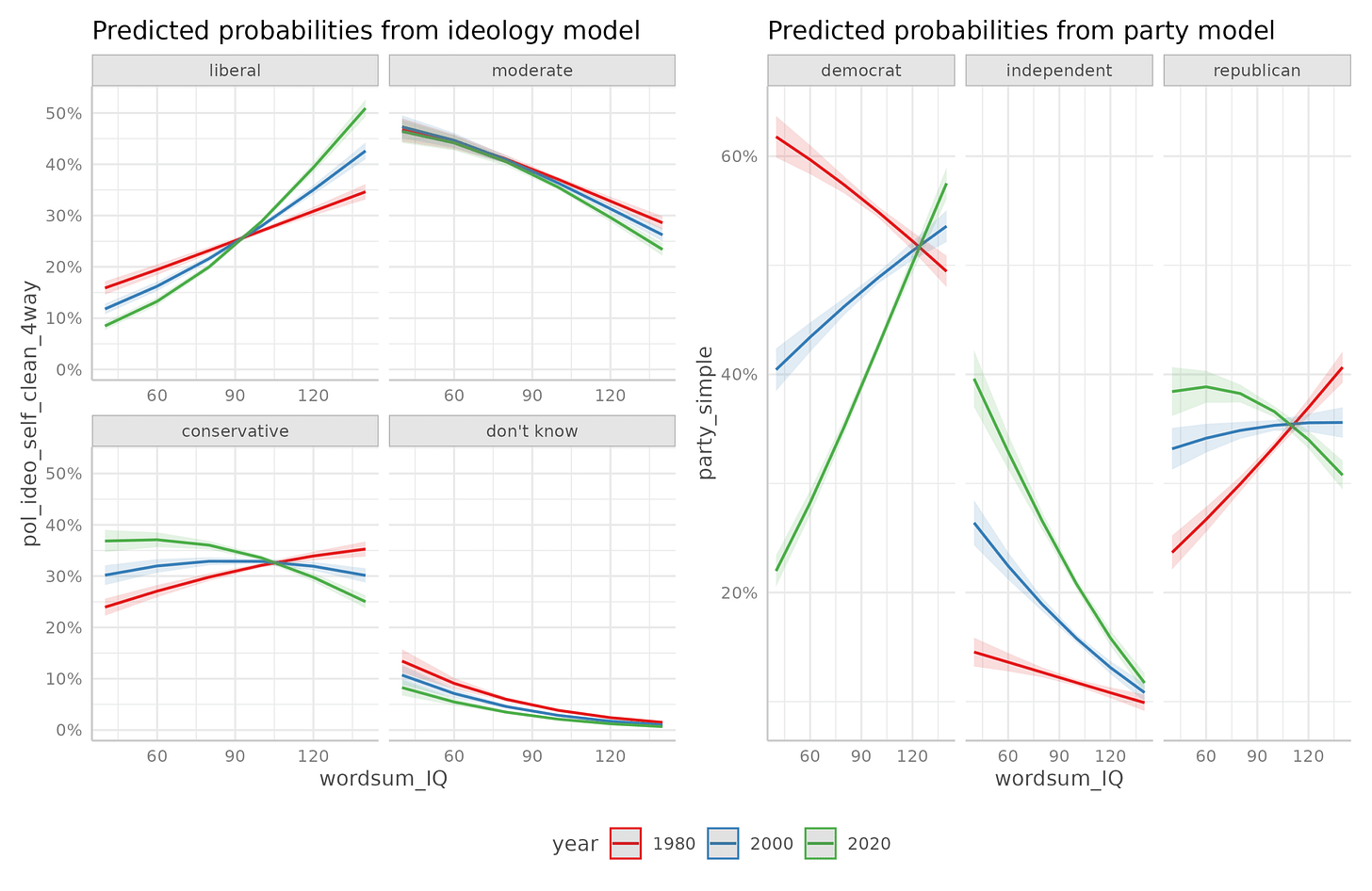

To give a concrete example of this, and I know I discussed it at length before, here’s the average IQs in the USA by political groupings over time (GSS data):

To make the plot:

Download GSS. Get wordsum variables (10 items). Score using IRT (mirt package in R).

Apply age corrections (for means and dispersion)

Apply Flynn effect correction (within each survey year, set White mean to 100)

Collapse party and ideology leanings to simplified format.

Findings:

Pre-1980, conservatism wasn’t the lower IQ ideology, but it has increasingly become so.

Republicans were the higher IQ party until 2016, probably not coincidentally this is exactly when Trump came in. To be fair, it was falling all along but it accelerated recently.

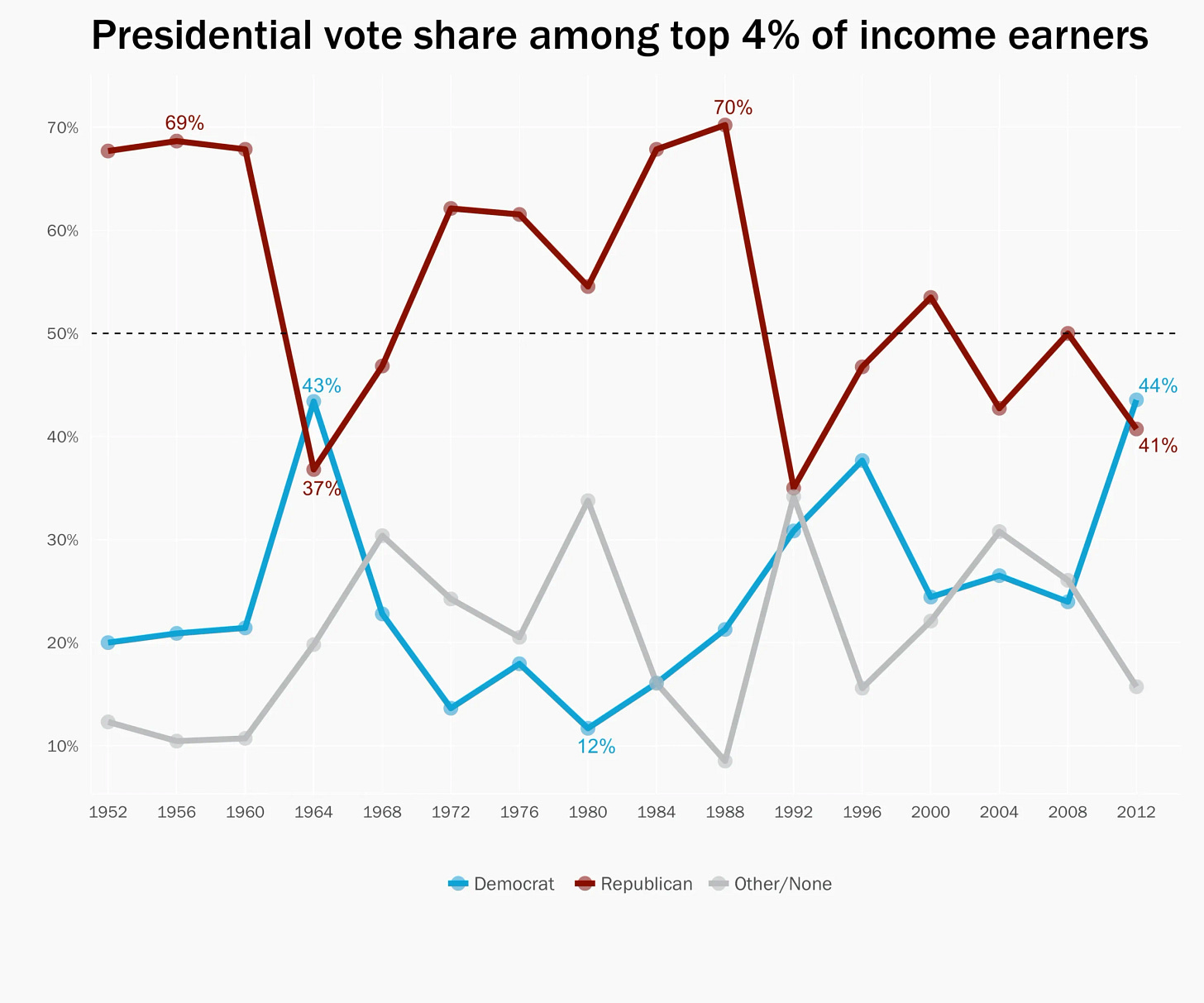

The latter finding goes well with the changes in the wealthy’s support for parties:

Thus, you can see that if you were trying to build some causal model of how certain aspects of personality cause political leanings, and you studied the data any time before 2016, you would find that higher IQ appears to lead to Republican party support. If you only looked at data after 2020, you may conclude the opposite. The fact is that the relationship depends on contextual factors.

To hammer the point home, you could also wonder if maybe we should include age, sex, race and so on in the models, and check what the effects of Wordsum IQ are:

It turns out controlling for these additional variables doesn’t matter that much but the model makes it very clear that large changes in the effect of IQ happened not over other factors.

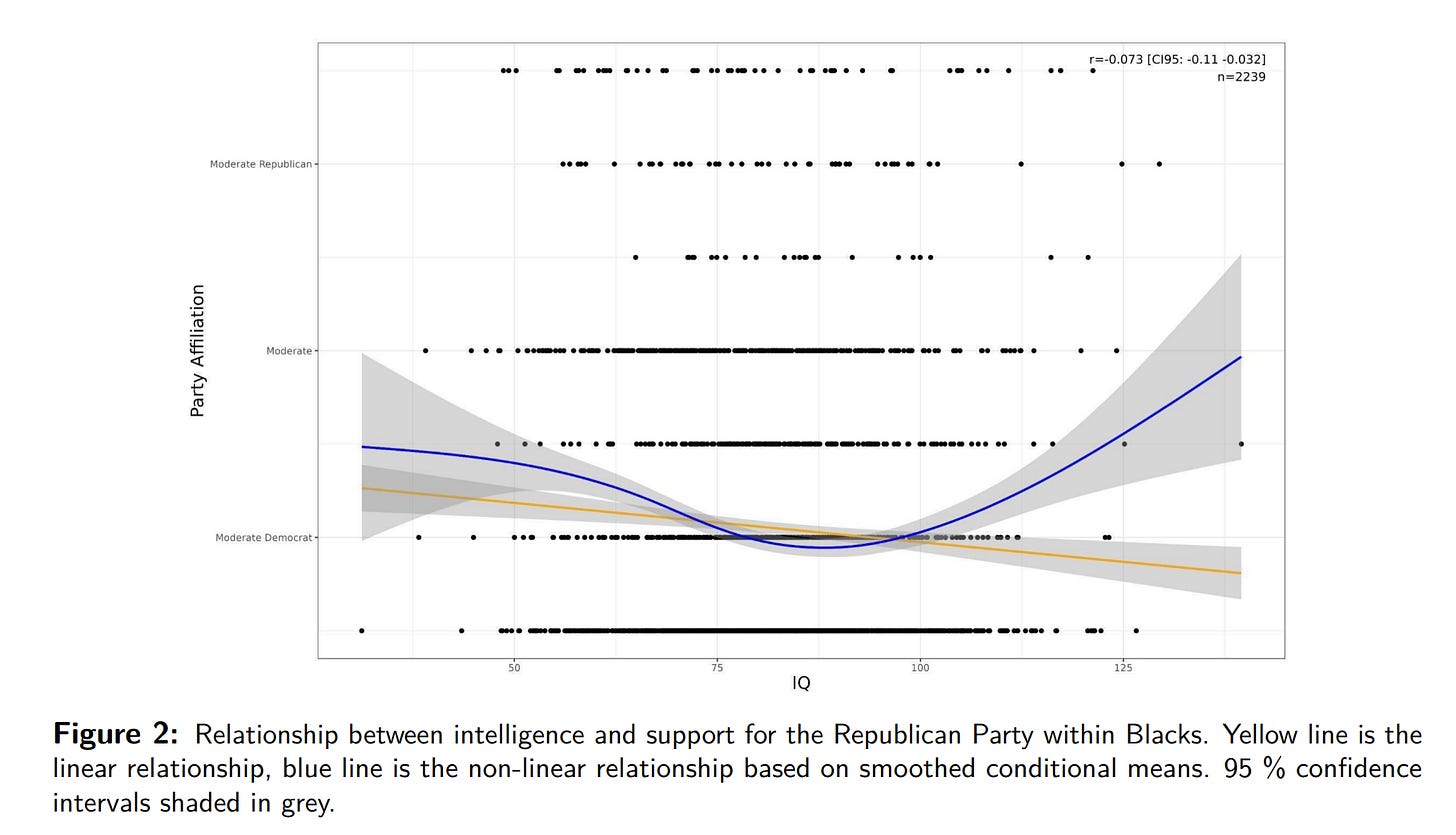

An additional example of the complexity of personality -> politics effects comes from Blacks in the NLSY 1979:

There is nonlinear, U-shaped pattern (Bell Curve meme). Clearly, coming up with a simple theory of how intelligence relates to Republican support, even at this particular time, would be difficult when it depends on both time and sometimes race. And this is all just within one country. In general, however, it is difficult to give many more examples because the long-running surveys and other large surveys do not in general have good personality scales.

Given this complexity, I think it is unwise to be fatalistic about whether it is possible to convince this or that political outgroup with facts and logic. The fact is that everybody in the past used to have different political views than us, but they had approximately the same genetic make-up. The changes in political views were not generally due to changes in genetics (immigration aside, which markedly changes the population composition which has potentially a large genetic effect).

While the rank-and-file population does not think deeply about politics (or anything else), and perhaps mostly copies their politics from their leaders, it is possible to convince relatively smart people in some cases. Whenever surveys are done of various academics or other experts, they always show a substantial minority who hold hereditarian views about this or that group difference, whether it concerns the sexes, races, or some other groups. Clearly, these people are living in a constant stream of egalitarian propaganda and almost all of their colleagues are left-wing, but nevertheless acquired different beliefs. There is some hope for the rest of them. If one doesn’t want to lose all elite support (evidence suggests this is a very bad idea for political influence), then some elites must be won over. They must be won over with facts and logic. What other options are there? Based on impressions I get from reading social media, going to conferences and so on, the young smart people of today are substantially more well-informed about the evidence for hereditarianism than prior generations. It is difficult to censor all the evidence away on the internet. Now that Musk owns Twitter and Zuckerberg has had a change of heart regarding censorship (COVID stuff), there is more hope than ever that platforms will not censor the evidence. Given that at the same time, the evidence has become extremely strong in the last 5-10 years, there is hope for the future. Even for the academics and other elites. Keep sharing the good word, so we can all end up better.

Cofnas's article brought up something I'd also thought about: is dogmatic adherence to a political ideology just the same mechanisms that cause dogmatic adherence to a religious ideology, occurring in a new secular context? I wonder to what degree the genes that predict religiosity also predict blind devotion to political causes. Do you know if there is any evidence of similar genetic or personality mechanisms?

I am always overwhelmed your articles. and I have a pretty good stat/psychometrics background, MS in psych etc. since I am retired maybe I lack the old energy to decipher an article such as this, but........It would be so nice to hear your take on all this in one paragraph.

I have not studied this subject much. but my take, is that there is a deep psycho/physiological, genetically (partially) caused difference between what today we call liberal and conservative. I suspect it has something to do with reaction to threat. Conservatives are suspicious, fearful a bit, quick to see and react to/prepare for threat. it is a "reptilian" level of personality. Those who are wired to be less alert to threat, tend to go liberal. Jerome Kagan's work on temperament comes close to describing this.