The issue with early interventions for cognitive traits

They improve the wrong skills for lasting gains

There are numerous intervention studies aim at improving cognitive traits. While one can aggregate these in ways that give the appearance of impact, when looked at properly they don’t really show any lasting gains (fade-out effect + publication bias + p-hacking). Every large planned analysis I’ve looked at found no lasting impact of any sort.

There can be several reasons for this. In one of my first published papers (2014), we forwarded the thesis that perhaps the gains were illusory to begin with in a sense. It turns out that when you look at intervention gains on a battery of cognitive tests (from the Head Start preschool program), the gains are larger on the less g-loaded tests. This suggests, but does not prove, that the gains were not in the g factor itself. The reason it does not prove this is that if there were true g gains as well as non-g gains, you would get the same negative correlation (Jensen’s method is only about relative changes, not absolute).

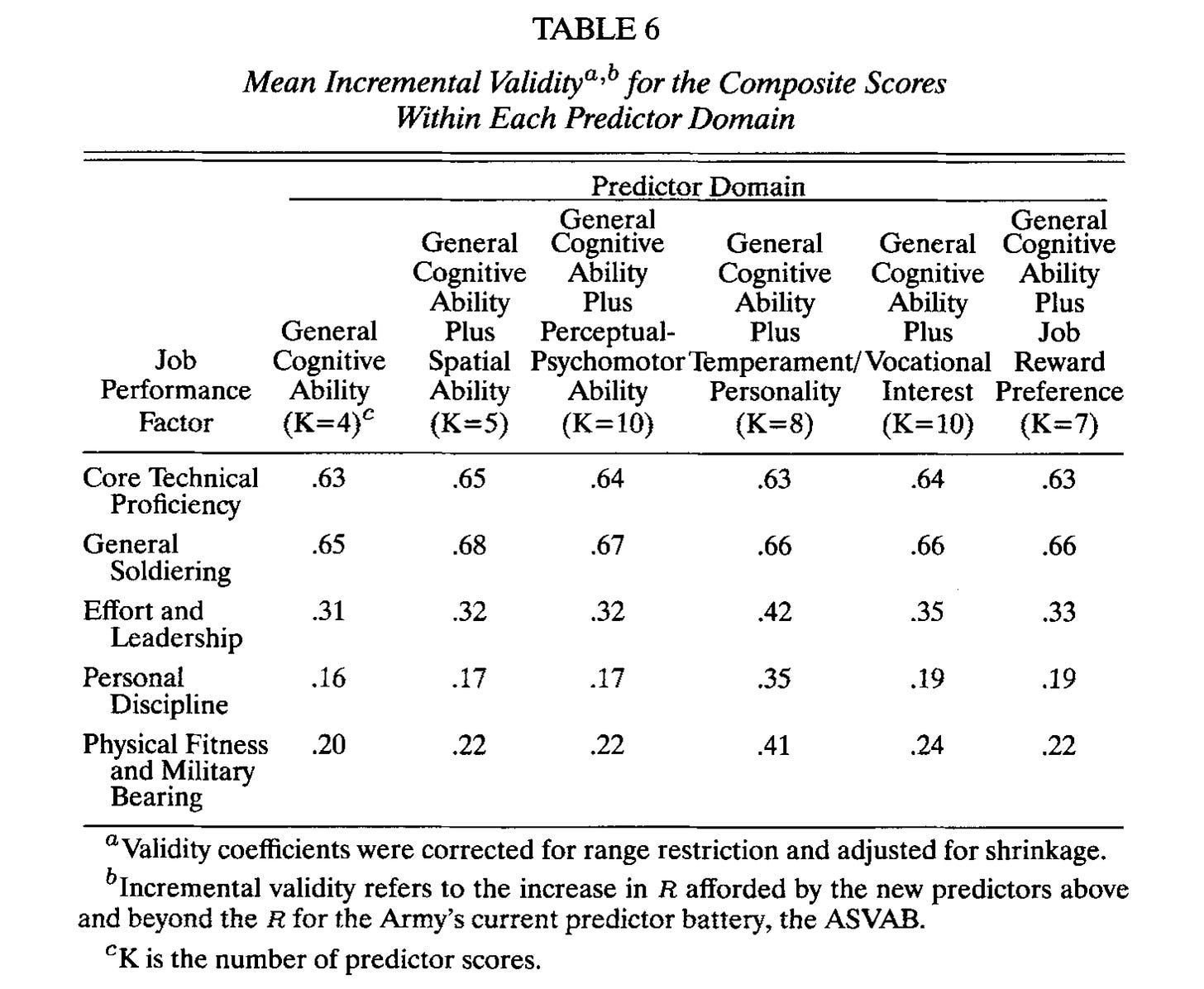

When you analyze cognitive batteries, what you usually find is that the tests don’t predict future outcomes equally. In fact, most of the validity is from the common variance, the g factor. This is what Arthur Jensen meant when he talked about g being the active ingredient in cognitive tests. This can be illustrated with data from the US military’s Project A form the 1990s: