The mirror self-recognition test as an intelligence test among humans

A new tool for national IQs

Recently, there has been much talk about national IQs, again. Here's the recent significant writings:

Jan. 13. Lyman Stone has a reply to my piece on within vs. between dysgenics. In it he writes: "As an aside, Emil may write a response to this article. If he does, I won’t write a rebuttal. Arguing about this online is literally his job. For many reasons, that means no protracted debate is likely to be productive.". A curious way to engage in scientific debate.

Jan. 15. Scott Alexander's How To Stop Worrying And Learn To Love Lynn's National IQ Estimates. I tweeted key parts of this and it somehow got 600k+ views on X. Scott also has a follow-up with the best comments (Jan. 16.).

Jan. 16. Cremieux wrote a masterful summary of why national IQs are valid, with most objections given and the answers to them. Much of this material is sourced from this blog or from our work, so readers may find it a very useful compilation.

Jan. 18. Seb Jensen has a reply to Lyman Stone, since he was criticizing our recent work on estimating global variation in intelligence. I guess Lyman might reply to this, as this was not written by me, and wasn't written at my suggestion either as I was unaware of his post. In any case, Lyman's main error is taking individual estimates too seriously, which we might term the Ron Unz fallacy due to his writings using this bad method with Lynn's database of studies.

Here I want to touch on something else, more speculative. There was this study from 2011 someone found which was making the rounds on X:

Broesch, Tanya Lynn, Tara Callaghan, Joseph Henrich, Christine Murphy, and Philippe Rochat. “Cultural Variations in Children's Mirror Self-Recognition.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 42, no. 6 (2011): 1019-1031.

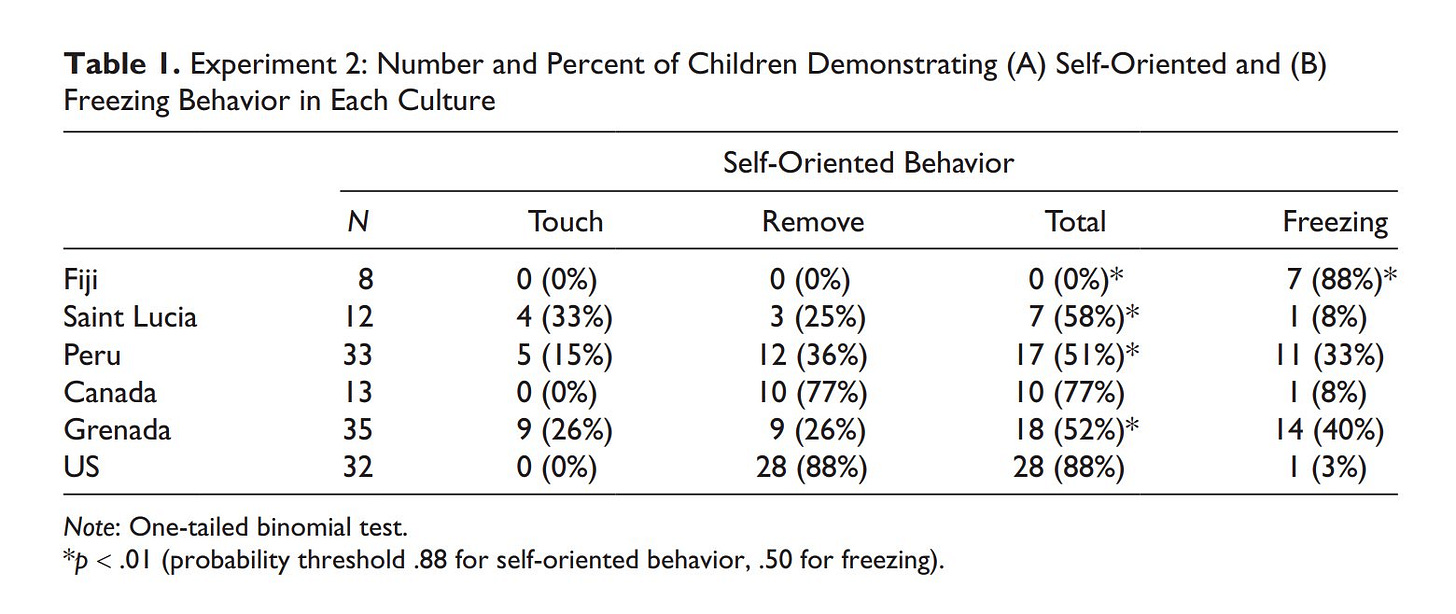

Western children first show signs of mirror self-recognition (MSR) from 18 to 24 months of age, the benchmark index of emerging self-concept. Such signs include self-oriented behaviors while looking at the mirror to touch or remove a mark surreptitiously placed on the child’s face. The authors attempted to replicate this finding across cultures using a simplified version of the classic “mark test.” In Experiment 1, Kenyan children (N = 82, 18 to 72 months old) display a pronounced absence of spontaneous self-oriented behaviors toward the mark. In Experiment 2, the authors tested children in Fiji, Saint Lucia, Grenada, and Peru (N = 133, 36 to 55 months old), as well as children from urban United States and rural Canada. As expected from existing reports, a majority of the Canadian and American children demonstrate spontaneous self-oriented behaviors toward the mark. However, markedly fewer children from the non-Western rural sites demonstrate such behaviors. These results suggest that there are profound cross-cultural differences in the meaning of the MSR test, questioning the validity of the mark test as a universal index of self-concept in children’s development.

Results:

Granted, the samples are small. Here's the context. The mirror self-recognition test has been used for decades to study intelligence, specifically in the form of self-awareness, across species.

Many people are familiar with cats and dogs and how they act around mirrors. They often get hostile or frightened and may attempt to fight their mirror image. But at some point they get it, and start ignoring mirrors. Did they figure out it's themselves? It appears so, but it is hard to know what animals are thinking. The idea of the mirror test is to place something on the skin of animals that they can't see (like between the eyes or on forehead), then put them in front of a mirror, and see if they remove it or touch it. If they do, it means they understand the mirror shows themselves. At least, it's hard to think of another interpretation. Generally, animals are sedated to avoid them just remembering that something was put on them at a specific location.

Human infants are almost completely helpless and don't pass the mirror test either. However, around 18-24 months of age, most of them figure it out. However, these studies were done on Europeans. The study above found that the maturation rate does not appear to be universal among humans. While this small study cannot tell us about the exact differences, or what their causes might be. Whatever the causes, however, there is some context for such differences. There is another widely studied test for cognitive development, namely, the Piagetian tests.

Two containers have the same amount of water, and in the view of the child, the water from one container is poured into another taller, shallower container. The child is then asked which container has more water. Obviously, they have the same, but children often think the taller container has more water, being fooled by appearances. Volume of containers can be deceptive. This is the conservation of volume test, but there are other similar tests. While one can use these to study interesting aspects of developmental psychology, it turns out that if a number of such tests are given to a child, they have a strong general factor. The score on this factor is very highly correlated, r = 0.85, with general intelligence measured the usual way. As such, Piagetian tests are really just another clever way of testing intelligence.

Regarding the mirror test, if we check which animal species are known to have passed, at least sometimes, the mirror test, the list mostly contains a familiar set of animals: dolphins, orcas (killer whales), chimpanzees, elephants, magpies. What is common about this list of animals? Well, it's a who's who of smart animals. It appears that ability to pass the mirror test relates to species average intelligence. Thus, it would not be surprising if the mirror test could also measure subspecies differences, which in humans we call race differences. The Broesch study is in fact not the only study to have tried this idea in humans. In their study they write:

However, more recent cross-cultural studies point to significant cultural variations in the onset of MSR. Keller and collaborators compared 18- to 20-month-olds from urban Greece, Costa Rica, Germany, as well as from a rural community in Cameroon, and they report a greater proportion of German, Greek, and Costa Rican children passing the test (more than 50%), compared to Cameroonian children (less than 4%) (Keller, Kartner, Borke, Yovsi, & Kleis, 2005; Keller et al., 2004). These authors correlate such variations to variations in parenting strategies that exist across these cultures, fostering more or less autonomy in the young child.

By checking the citations, I was able to find 2 additional studies: Kärtner et al 2012 (another replication with Indians and Africans), Ross et al 2016 (Turks and Africans). There may be more studies. All studies find differences roughly in line with known group differences in intelligence. This mirrors (pun intended) the findings for the Piagetian tests, with one summary already in 1972 writing "the rate of operational development is affected by cultural factors, sometimes to the extent that the concrete operational stage is not reached by large proportions of non-Western samples.". I found one study that checked whether this idea works within groups, namely, does passing the mirror test correlate with later measured intelligence? Yes, say Lewis and Minar 2021. They measured mirror test at age 18, and correlated this with the primitive age 3 Bayley scale of development, as well as vocabulary knowledge. They report correlates around 0.20, but the mirror-test score is binary, so this Pearson correlation has to be adjusted upwards quite a bit, and the Bayley scale has to be adjusted for reliability as well. If both of these are done, perhaps the correlation will be around 0.50. This seems sensible.

It would appear, then, that one could perhaps construct national IQ maps based only on mirror self-recognition tests. They are non-verbal, which would be a welcome addition to the already existing body of evidence. This is not to say that one cannot come up with plausible confounders relating to the role of mirrors, prior exposure etc. Since these tests are impractical to do, requiring infants of a specific age range, they are not likely to be commonly administered in large numbers across poor countries, where critics are most keen on questioning the results. Better would be a project of administering non-verbal reaction time-related tests, though these also can have issues if human groups differ in a reaction time speed orthogonal ability to general intelligence. No test is perfect, which is why the problem must be attacked from every angle.

WRT the mirror test and differences between some groups and others, I wonder if there is any consideration given to the idea that in some groups there is little household familiarity is with mirrors. Children in such households may even never have seen a mirror, or perhaps only infrequently, while in more sophisticated societies there could well be much earlier, and more frequent exposure to mirrors, and how images are reflected in them.

It's absolutely hilarious to do it with your toddlers😂 then again, toddlers are just hilarious🎉

So basically this is yet another stream of accumulating nomological network of evidence for HBD. It's ideology more than ignorance that is stopping people from accepting it. I love this definition of woke by Nathan Cofnas...