Thoughts re. Relativity, a very short introduction (Russell Stannard)

Relativity - A Very Short Introduction

The idea of reality being four-dimensional is strange and counter-intuitive. Even Einstein himself at first had difficulty accepting Minkowski’s suggestion – though later he was won over and declared ‘henceforth we must deal with a four-dimensional existence instead of, hitherto, the evolution of a three-dimensional existence’. Not that this is meant to imply that time has been reduced to being merely a fourth spatial dimension. Although it is indeed welded to the other three dimensions to form a four- dimensional continuum, it yet retains a certain distinctiveness. The light cone encircles the time axis, not the others. Absolute future and absolute past are defined in relation to the time axis alone.

Acceptance of a four-dimensional reality is difficult because it is not something that lends itself to easy visualizing – indeed, forming a mental picture of four axes all mutually at right angles to each other is impossible. No, we must dispense with mental pictures and simply allow the mathematics to guide us. One of the disconcerting features about four-dimensional spacetime is that nothing changes. Changes occur in time. But spacetime is not in time; time is in spacetime (as one of its axes). It appears to be saying that all of time – past, present, and future – exists on an equal footing. In other words, events that we customarily think of as no longer existing because they lie in the past, do exist in spacetime. In the same way, future events which we normally think of as not yet existing, do exist in spacetime. There is nothing in this picture to select out the present instant, labelled ‘now’, as being anything special – separating past from future.

We are presented with a world where it is not only true that all of space exists at each point in time, but also all of time exists at each point in space. In other words, wherever you are seated now reading this book, not only does the present instant exist, but also the moment when you began reading, and the moment when you later decide you have had enough (perhaps because all this is giving you a headache) and you get up and go off to make a cup of tea.

We are dealing with a strangely static existence, one that is sometimes called ‘the block universe’. Now there is probably no idea more controversial in modern physics than the block universe. It is only natural to feel that there is something especially ‘real’ about the present instant, that the future is uncertain, that the past is finished, that time ‘flows’. All these conspire against acceptance of the idea that the past still exists and the future also exists and is merely waiting for us to come across it. Some leading physicists, while accepting that all observers are indeed agreed on the value of the mathematical quantity we are calling ‘the distance, or interval, between two events in four-dimensional spacetime’, nevertheless deny that we must go that extra step and conclude that spacetime is the true nature of physical reality. They maintain that spacetime is merely a mathematical structure; that is all. They are determined to retain the seemingly common-sense idea that the past no longer exists, the future has yet to exist, and that all that exists is the present. I suspect you are inclined to agree with them. But before lending them your support, it is worth considering in more depth what your alternative to the block universe might be.

It is all very well saying that all that exists is what is happening at the present instant, what exactly do you mean by that? Presumably you mean ‘me reading this book in this particular location’. Fair enough. But I imagine you would also include what is happening elsewhere (literally elsewhere) at the present instant. For example, there might be a man in New York climbing some stairs. At the present instant he has his foot on the first step. So, you will add him, with his foot on that step, to your list of existent entities. But now suppose there is an astronaut flying overhead directly above you. Because of the loss of simultaneity of separated events, he will disagree with you over what is happening simultaneously in New York while you are reading this book. As far as he is concerned, the man in New York, at the present instant, has his foot on the second step – not the first step. Moreover, a second astronaut flying in a spacecraft travelling in the opposite direction to the first arrives at a third conclusion, namely at the present instant the man in New York hasn’t even reached the flight of stairs yet. You see the problem. It is all very well saying that ‘all that exists is what is happening at the present instant’, but nobody can agree as to what is happening at the present instant.What exists in New York? A man with his foot on the first step, or a man with his foot on the second step, or one who has not yet reached the stairs? As far as the block universe idea is concerned, there is no problem: all three alternatives in

New York exist. The argument is merely over which of those three events in New York one chooses to label as having the same time coordinate as the one where you are. Relative motion means one simply takes different slices through four-dimensional spacetime as representing the events given the same time coordinate, ‘now’.

But of course, the block universe idea also has its problems.Where does the perceived special nature of the moment ‘now’ come from, and where do we get that dynamical sense of the flow of time? This is a big unsolved mystery, and might remain that way for all time. It does not seem to come out of the physics – certainly not from the block universe idea – but rather from our conscious perception of the physical world. For some unknown reason, consciousness seems to act like a searchlight scanning progressively along the time axis, momentarily singling out an instant of physical time as being that special moment we label ‘now’ – before the beam moves on to pick out the next instant to be so labelled.

But now we are venturing into the realms of speculation. Let’s get back to relativity . . .

Actually, it was just getting intresting. Perhaps i'll have to read some of that filosofy of time after all... -

We have seen that the faster one travels, the more time slows down. Reach the speed of light, and time comes to a halt. This appears to raise the question as to what would happen if one were to accelerate still further until one was travelling faster than the speed of light.What would that do to time?Would one go back in time? One hopes not. Such an eventuality could cause all kinds of confusion. Suppose, for instance, one were to go back and accidentally run over one’s grandmother – and this before she had had a chance to give birth to your mother.Without you having a mother, how did you get here in the first place!? Fortunately, this cannot happen. As mentioned earlier, nothing can travel faster than light. How does that come about?

Actually, backwards time travel is not a logical problem (but it is a fysical problem). It follows that since u are here, u did not actually go back and kill ur grandwhatever-relative. See Swartz writings on this subject: e.g. http://www.sfu.ca/~swartz/time_travel1.htm -

Does the fact that we cannot accelerate to the speed, c, rule out all possibility of travelling faster than light? Strictly speaking, no. All we are saying is that it is impossible to take the kind of matter we are familiar with and accelerate it to superluminal speeds. But that does not rule out the rather fanciful possibility of there being a second type of matter, created at speeds exceeding that of light, and which can travel only at speeds in the range c to infinity. Such hypothetical particles have been given the name tachyons. Some years ago they were the subject of much speculation. It was noted, for example, that observers made of tachyon matter would consider that speeds in the tachyon world were confined to be less than c, and that it was our type of matter that would have speeds lying in the range c to infinity. But enough of that; there is absolutely no evidence for tachyons; they are but the subject of unfounded speculation.

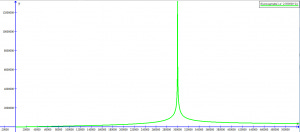

But neutrinos are so cool. :P There are even more strange things that happen if something moved at >c. First, take a look at the graf for momentum made from the relativistic equation p=mv/sqrt(1−v2/c2) (i have set m=1 and c=300000)

Notice how there is no values for x>300000. This is becus after that the v2/c2 clause is more than 1, which makes the sqrt take the sqrt from a negative number. This doesn't work. However, if there really was FTL travel, how wud we alter the equation? How about the simple p=mv/sqrt(abs(1−v2/c2))? This gives the same results for x=[0;30000[ but after that also gives values for x>300000. It looks like this:

This is rather strange to interpret, as mentioned before. Becus at FTL speeds, when the particle speeds up, it loses not gains momentum! Basically, one cud harvest energy from these particles by speeding them up. How very strange. Another thing to note is that one cudn't continue doing this since if x→∞, then f(x)→3, but only if one looks at x>30000, becus at x<30000, if x→∞, then f(x)→∞. -

That's interesting. -

In conclusion, the weight of evidence for the existence of supermassive black holes at the centre of galaxies is considered to be overwhelming.

-.- not sure if intended pun or not. -