Does assortative mating work?

In theory, yes, but direct empirical evidence isn't so strong

In my recent post about differences on the tails, a good comment was posted by Kristine:

Is there any correlation between IQ gap and divorce, I wonder...

The generation observation among humans and other species is that mates are more similar than would be expected by chance, called social assortment, or assortative mating. It’s part of the broader phenomenon of social homophily, or like attracts like (’birds of a feather flock together’). Numerous studies have shown that friends are more similar on various attributes than expected by chance, including intelligence, but also of course age, social background, interests, politics, and so on. This creates a kind of natural echo chamber which can be further enhanced with the internet since this enables people to seek out and associate with people even more similar to themselves than they could otherwise find in their face-to-face networks. At least, that’s the theory.

We can perhaps supply some evolutionary speculative theories about why social homophily exists in general. In terms of inclusive fitness theory, associating with and helping people with similar trait levels to yourself would in effect have a slight positive effect on your inclusive fitness, as the specific genetic variants that make you smart, tall etc. are also in general found in other smart, tall etc. people. This effect would be very slight though due to polygenicity (many genetic causes of small effect for most traits). The simpler overall theory of egoism is just that organisms like themselves in general, and thus also in effect like others who are similar to themselves. It’s easy to think of it this way for humans, but whether this model makes sense for rabbits or salamanders is another thing.

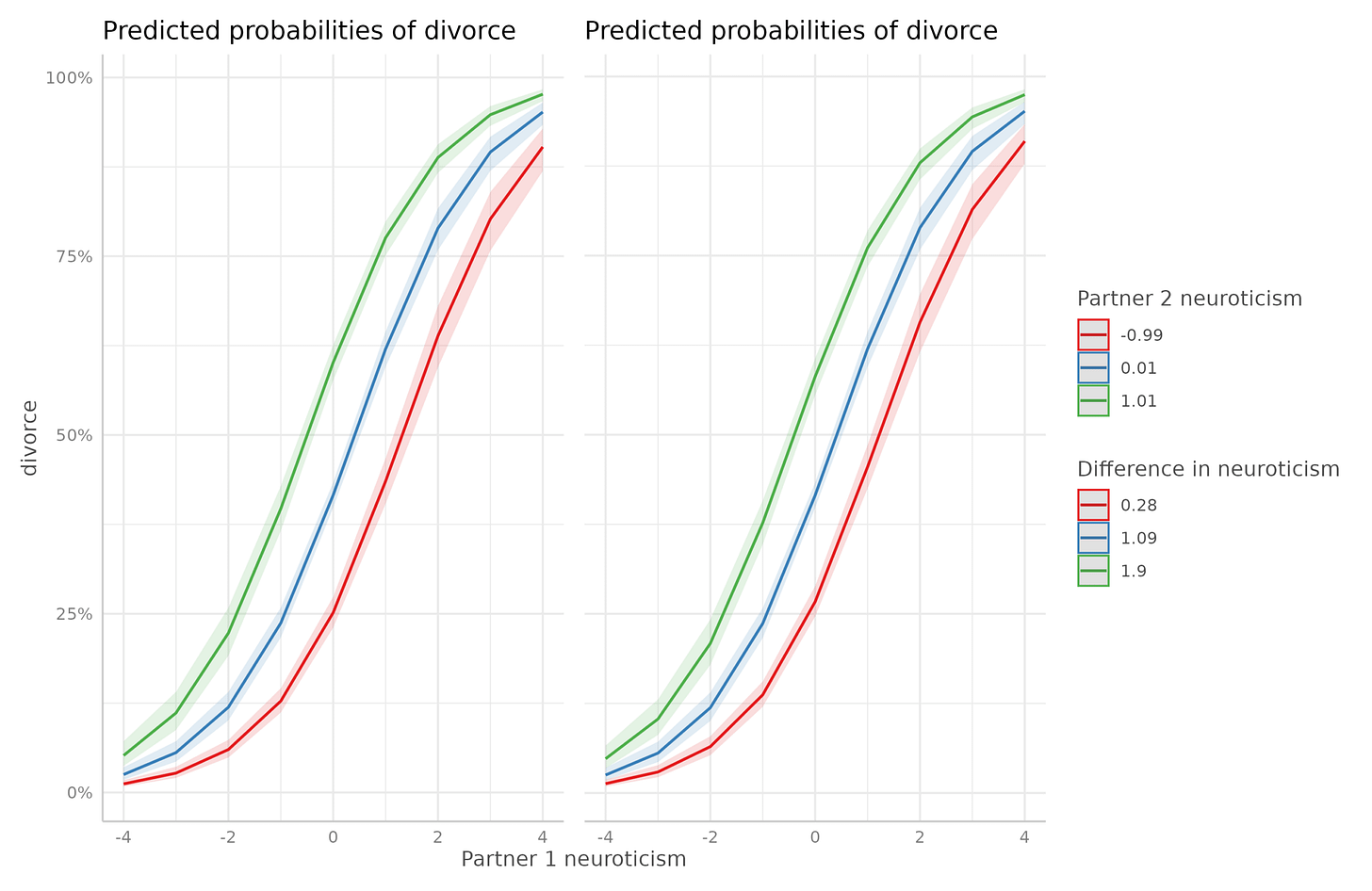

Whatever the foundation for this preference seen in general in the animal and human worlds alike, we can ask whether it actually works. Do more assortatively mated couples last longer together? The answer is surprisingly difficult to find for two reasons. First, it is hard to study empirically since it requires data for dyads (pairs), which is harder to recruit (maybe the wife wants to contribute to the study but the husband doesn’t). Moreover, it requires longitudinal data. You measure the couples at time X and then at some later point Y with some years in between. This requires tracking people over time. Second, since it is a kind of interaction effect statistically, it requires high power and precision of measurement. In effect, we are trying to model the chance of a break-up of some kind (formal divorce or separation, or just a more general relationship dissolution) as a function of the difference in the mate’s score on some trait. This is more tricky when there are differences between the sexes on the trait in question, say, neuroticism. If the average woman is 0.50 SD higher than the average man, then most couples will tend to have a fairly big gap absent some spectacular assortment. In general, thus, researchers may use within-sex norms for the traits instead. It’s not so clear which is best here before looking at some data. Finally, additive effects will tend to dominate any interaction effects. I’ve previously written about how people who are high in openness and neuroticism are more likely to divorce in general. The effect seems to be additive, so that couples with 2 persons with high neuroticism are more likely to divorce than couples with 1 high and 1 low. This goes against a protective effect of assortment, but could be consistent with a small effect. To see what I mean, here’s some simulated results:

Here we can see that the effects of neuroticism are additive (leftmost plot), and there is additionally a protective effect of assortment (rightmost plot). A more clear way to under how this works is to use color as a third dimension:

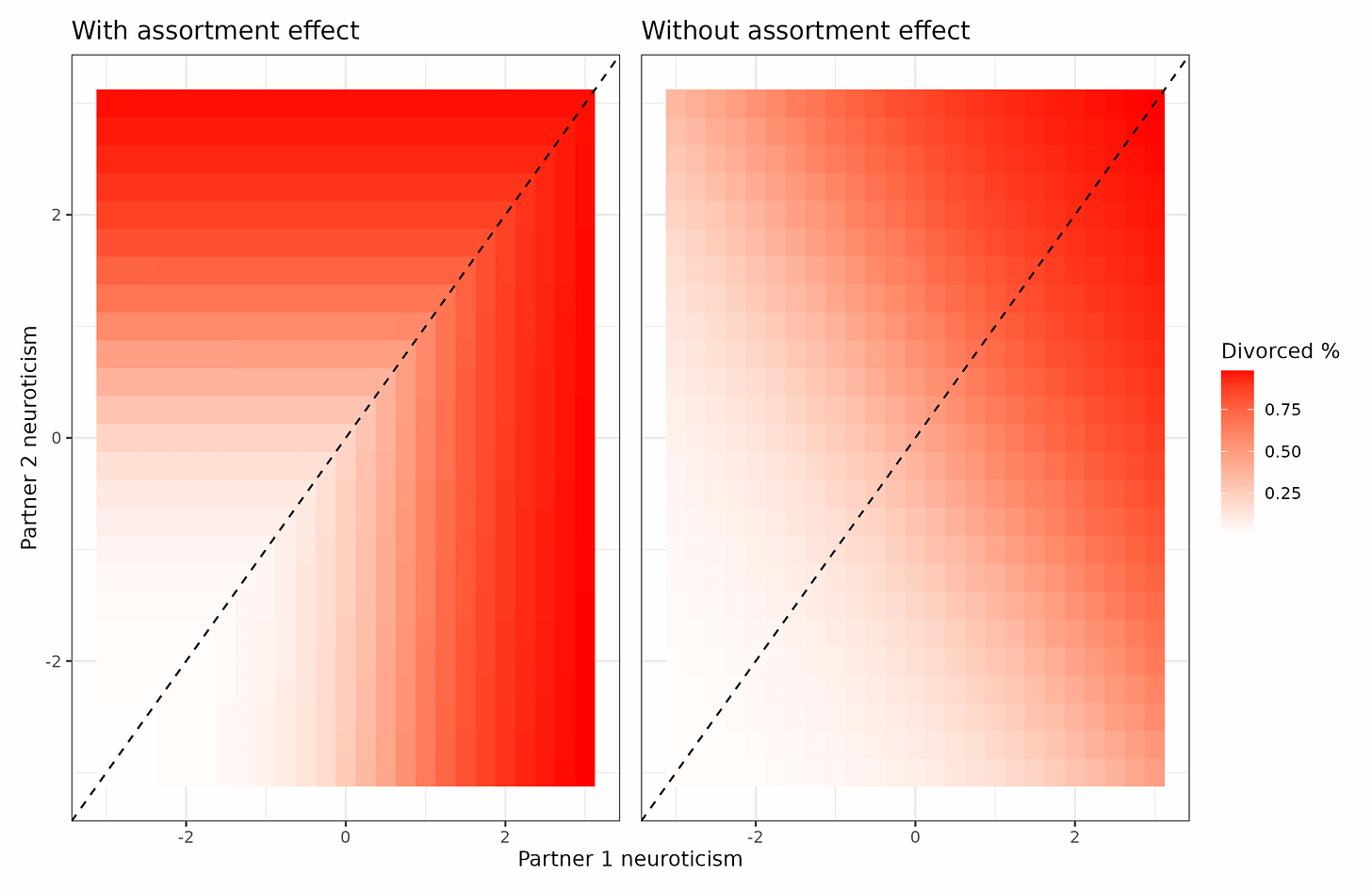

The rightmost plot shows the main effects only. In this case, the effect of neuroticism is just how much of it you have in a relationship, it doesn’t matter how it is distributed. Because of this, there are lines of equivalent risk going from the top left to bottom right, since e.g. +1 + -1 = 0, and 0 + 0 = 0. In the leftmost plot, we see the effect of the assortment giving rise to the lines horizontally and vertically. The lowest risk of divorce is found for couples that are perfectly matched (on the central line), at any given level of average neuroticism within the couple. These results are purely hypothetical to give us an understanding of how the statistics would work out. Probably the strength of the dissimilarity effect is not as large as I have assumed here, but I wanted it to be easy to discern on a plot.

Anyway, so are there some studies looking at this kind of thing? There’s a study of mental health diagnoses, that I covered before when writing about lesbian divorce rates: